Making the Decision to Re-Release

In 1981, filmmakers Carolyn Strachan and Alessandro Cavadini received acclaim for Two Laws/Kanymardra Yuwa, a documentary about the struggle for Aboriginal groups from the Northern Territory to live within both their own and Australian law. Screenings in Australia, including at the Sydney Opera house and throughout Europe, eventually brought Strachan to the United States for the 1982 Margaret Mead Film Festival.

On opening night, a French journalist told her that Two Laws had been voted first prize at a festival in Paris but that the jury downgraded it to the “most notable” category. “The old guard challenged the nomination,” she recounted recently by phone.

A mystified Strachan wondered what about Two Laws prompted such a reaction?

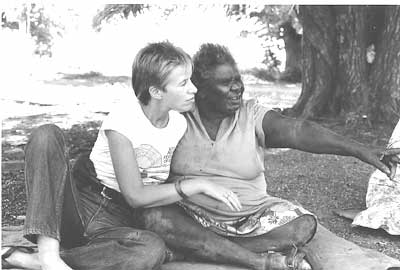

As admirers of films by French anthropologist Jean Rouch, Strachan and Cavadini were determined to follow the lead of the community that invited them to make a film about their loss of sacred lands. In a practical sense, that meant becoming a member of the Borroloola peoples’ kinship groups and observing Aboriginal decision-making traditions (Strachan sat with women; Cavadini sat with men, for example). In a formal sense, it meant using a wide-angle lens to depict an array of characters in their landscape, and determining the film’s structure by committee.

The result — a four-part story that includes ensemble re-enactment — refuses a conventional one-character narrative arc. Many scenes depict the Borroloola community members “sitting on their own land” as they call it, in real time. The intentional pace enlivened some viewers and tried the patience of others. Strachan persevered with the goal of understanding and bridging that gap. But her knocks on the doors of American film distributors went unanswered, even slammed shut.

Twenty-six years later, she lives in the United States teaching film at Hunter College, and has decided to make Two Laws available for the first time on DVD through Facets Multimedia. The re-release includes both the original Two Laws as well as an annotated version for educational purposes, audio commentary from early champions filmmaker Jill Godmilow and professor Bill Nichols, a written film guide, and other features discussed below. The following Q and A was culled from two conversations by phone.

Tell me about the importance of being invited by the Borroloola community to tell their story. How did that come about?

It was a very tricky political situation at the time. Young radicals (they called themselves the black power) had sent us off to make films to record the historical origins of their anger. By 1981 we were bowing out, we felt we had done our bit. The Borroloola people had seen our work and asked us to make another film. We felt uncomfortable and told them there were young black filmmakers who may resent us. But they said, ‘We want you, we think we can manipulate you, we think you’ll respect our law and your egos will not get in the way.’ We were persuaded, and agreed that the main thing we’d do is surrender all of our filmmaking knowledge, and what comes out of that community is what we’ll get.

I understand that you and Alessandro would string up a sheet between trees to project films for the Aboriginal communities in order to invite their active participation in the filmmaking process.

Behavior around the campfire is a very complex system and it took months to learn. We would travel from camp to camp and learn all of their skin relationships and kin relationships; I didn’t necessarily learn everybody’s name, but I had to know all the relationships in their language to function. At the same time we were showing films and the next day we would have meetings; people would discuss what they liked, they talked and debated, and that’s how we evolved ideas for this film. Nothing could take place without everyone being involved and without total consultation.

Can you describe how the group helped you arrive at the decision to use a wide-angle lens?

We had this hunch. We had already been working for many years with Aboriginal people, when we got there, we would shoot around with the wide-angle, send tests down to the lab, and show the tests. It was unanimous vote: you could see the land and include many people in one frame.

For a lot of the films made with Aboriginal subjects, Inuit, or African peoples, the format was usually to follow one person or one family to tell the story. But these groups didn’t like it. They’d ask ‘Why is one person doing the talking and no one else?’ The idea that a camera would zoom in on one face was not correct to them. They challenged one of the basic tenets of documentary filmmaking: to find a charismatic character to tell the story. We were happy to let that go.

To what extent were you filming with the thought that you would figure out structure later, and to what extent were you developing a structure as you shot it, based on the interaction between you and the film’s participants?

It was definitely emerging as we were filming. If you look at the film, it is much more tentative during Police Times [part one]. We did the first three parts chronologically. Every Thursday we would receive footage and show it around, once they saw that, they started seeing what they wanted and what they didn’t want. People say you can never have communism — people are too selfish and too greedy — of course not in our culture — but I have seen it work. They were communally directing our film.

What made you decide to re-release the film?

I have watched people watch it on a TV screen and they didn’t last 20 minutes. In conventional documentary style, you edit on the person talking; you guide the viewer to what you want them to see. Here we are opening up this huge frame, inviting the viewers to scan the frame and make up their own minds. It worked much better on 16-mm film, projected on a screen.

In 1982 we decided to distribute only on film [through the Sydney Filmmakers’ Cooperative] and to be screened only through a film projector. In those days, we projected everything. As years went on, I was teaching in more classrooms with overhead projectors and video projectors and thought, okay, if this is the trend and we can screen the film big, then the technology will allow us to release it again.

DVD formats and distribution trends have also led to an expansion of the story through “extras.” How did you make decisions about what to include?

The first thing we wanted was to have an Aboriginal person introduce the film to keep some remnants of its activism. In the process of taping Malarndirri [McCarthy], who is in the state assembly, she said, ‘I want you to come back and film the handback. All the people want to see you.’ Two Laws is about their land claim and the denial of most of it. Many years later they finally got some of their islands back. We thought it was an important addition. We couldn’t get a boat and had to wait days and days by the riverbank. We finally arrived the day of the handback and shot all day. We also wanted to add the mining company bit [a separate three-minute extra] because they had lost the sacred land of Bing Bong to the mining company many years before.

We knew Jill [Godmilow] and Bill [Nichols], who do voice over commentary, would give an academic cinema reading of the film, and I thought we needed to have another context from the aboriginal ethnographic world. Faye Ginsburg [director of the Center for Media, Culture & History] is a big fan of the film and offers the ethnographic perspective.

What kind of criticism has the film roused?

Even at a screening this year, maybe a quarter of the audience got up and walked out. One person said he hated the film, told me it is biased, that it’s all from the Aboriginal point of view…

How do you respond to the accusation of bias?

I’m proud of it! It’s about time the people have been given a voice.

Yet sometimes the film gets praised as the authentic piece. The one and only from their point of view. But it’s a mediation between filmmakers and the people. They used us to get their message across and that’s what it’s all about. To think of it as the definitive piece is dangerous.

Also, it only reflects a particular moment in time.

That’s right. If we had gone back six months later, it could have been a different film.

Can you tell me about the “getting it out there” part of the re-release? I know you have forthcoming coverage in Studies in Documentary Film and Framework: The Journal of Cinema and Media. What about screenings? Festivals? Classroom visits?

I haven’t quite worked it out. I didn’t think that it would be possible to put it into a festival because it’s old. I asked Facets if they would give me some postcards to send out to cinema and anthropology departments in the United States. In Australia, Allesandro and I are showing it at Monash University at the end of June for a symposium, which is the official release. Hopefully I will get more people in Australia to see it, get it in to other kinds of journals. I am making myself available.

What advice would you give to other filmmakers considering a re-release?

I think we were all doing much more pioneer work then. I showed it to my students. They were all bored… they aren’t so interested in history, but without history, we just make the same mistakes. I use a lot of ancient films made in the 20s to show my students how adventurous films were. Documentaries were not just one form with talking heads as it is often assumed or expected now. We need to show students that there is room to open up the form again and show that experiments in form create new messages.

Additional Reference:

In addition to the added DVD video features and written guide that accompany the Two Laws DVD, the website includes reviews, academic papers, filmmaker biographies, and other resources.

Facets Multimedia – http://www.facets.org/asticat

Regions: Australia & New Zealand