The 11th Beijing Independent Film Festival: Shutdown Report From China

Gen Carmel spoke with two festival participants, and tracked down the elusive full festival program.

While the pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong resulted in the shutdown of the popular social media site Instagram in mainland China last week and prompts continued monitoring by media this week, it was only last month that we heard the story of another crack down on alternative media in the People’s Republic of China. The shutdown of the 11th Beijing Independent Film Festival this August was not the first time that local authorities have stepped in to halt the proceedings of the annual fest organized by the Li Xianting Film Fund. However, 2014 is reported by participants to be the first year that any physical force was used by authorities, leading to a violent confrontation, the confiscation of the festival’s programs and films, the confiscation of the Li Xianting Film Fund’s film archive, and the overnight detainment of festival leadership, as reported by The Guardian, Associated Press, and other news media.

The Li Xianting Film Fund is located in Xiaopu, a neighborhood in Songzhuang Village, about an hour’s drive outside of Beijing. In Xiaopu, courtyard homes, restaurants, and art studios are tucked away in a network of alleys beyond the town’s busy main street. Songzhuang is the encompassing art district that is also home to the Fanhall Center for the Arts, the Songzhuang Art Museum, and other creative institutions and private studios.

In other suburbs and villages around Beijing, there are art districts where one can find independent filmmakers living and working, and independent film festivals and screenings open to the public, but Songzhuang has become host to one of the most influential gathering points for mainland Chinese independent filmmakers. As it’s gained national and international notoriety as one of the premier events for discovering new works by both emerging and experienced independent Chinese film and video artists, while also not allowing for any review of the independent works by local or national media censors, it’s consequently become the target of these repeated shutdowns.

For mainland Chinese filmmakers, “independent” usually means independent from the big budget Chinese studio system, and independent from the government censorship process administered by the State Administration of Radio Film and Television (SARFT). However, there can be various degrees to this distinction. While some independent films made in China may be produced with no intention of seeking government approval, and for a variety of reasons, there are some filmmakers who may originally seek SARFT approval for a particular work and then fail to obtain it at the pre-production, fine cut, or distribution stage, subsequently choosing to complete and distribute the film independently. Both degrees of independent films can exist within the same domestic independent distribution space, which consists of independent film festivals and screenings at universities, a few unofficial theaters like Fanhall, art spaces, and hundreds if not thousands of other small independent venues like bookstores, bars, restaurants, and cafes. More well-known independent festivals like the Beijing Independent Film Festival provide a rare platform within China for such works to win awards and gain notoriety among an interested but limited audience, as an alternative to the state-controlled theatrical market that these independent works have no legal access to.

I caught up with several people who attended the festival to ask for their account of what took place this year, and for their thoughts on what this newest shutdown means for independent filmmakers in mainland China. I also sought to find out more about the films in this year’s BIFF program, the details of which have been almost entirely missing from all English-language news of the event, in part because so much of the festival’s digital and printed PR materials were confiscated, and because there was very little opportunity for any films to be viewed. The fact that almost no films were watched is unlike past years at the festival, when its official cancellation didn’t deter filmmakers and participants from getting together for private screenings at the Film Fund offices, or from reportedly circulating film screeners to be watched in private homes and hotel rooms.

Benny Shaffer is an anthropology PhD student at Harvard who curates the Emergent Visions film series, bringing independent Chinese cinema to the Fairbanks Center for Chinese Studies at Harvard. He is also a former Fulbright Fellow who has researched and attended the Yunnan Multi Culture Visual Festival (Yunfest), another well-known independent film festival in mainland China, located in the Southwestern city of Kunming. Shaffer was in China this summer and spent some time at the Beijing Independent Film Festival, so I asked him about his experience, and his thoughts on BIFF in relation to other festivals like Yunfest:

Gen Carmel: As a festival participant this year, under what conditions were you able to watch any of the programmed films as planned?

Benny Shaffer: I watched one film, which was not part of the festival–a rough/director’s cut of Qiu Jiongjiong’s Betrayal: The Story of Zhang. At a previous visit to Songzhuang, I watched Huang Xiang’s Gossip, which was to be screened at BIFF.

GC: To the best of your knowledge, what was the audience demographic at the festival this year? Did you notice a more general audience of “cinephiles,” in addition to filmmakers, curators, researchers, journalists, and critics?

Shaffer: Not many “cinephiles,” mostly people who work in/with/around cinema—filmmakers, curators, journalists—only one or two researchers and critics that I recognized. A lot of foreign researchers seem to have given up or show less interest in the festival because they assume that it will be shut down.

GC: What do you think differentiates this festival from other independent film festivals in China? For your research and curation, what makes you continue to return to this festival every year?

Shaffer: Because of its proximity to Beijing, which serves as both the political and the cultural capital of China, the festival at Songzhuang has faced an escalating degree of restrictions, though this year was certainly the most extreme. Given the location of the festival, the filmmakers and participants have come to represent a kind of outlaw contingent, even though most of the films that are programmed are not overtly political, and the organizers are obviously not trying to come into a direct confrontation with the authorities.

The Yunnan Multi Culture Visual Festival—aka Yunfest—has similarly faced a number of complications in recent years, despite its location in the provincial capital of Kunming, far from Beijing. For the years when I was able to attend the festival in 2009 and 2011, it was held at the Yunnan Provincial Library. The collaboration between the Yunfest organizers and their danwei [work unit], the Yunnan Academy of Social Sciences—curator/director of the festival, Yi Sicheng, is officially employed by the YASS, along with filmmaker He Yuan and others—helped to legitimize the festival and create a forum that was well-attended and open to the public.

It’s unclear exactly why the situation became so tense and problematic last year for Yunfest, forcing the festival to be shut down before any gatherings were held. It is likely tied to the same problems faced by the other festivals, primarily in Beijing, Nanjing, Chongqing.

GC: If BIFF were to completely cease operating, how do you imagine that would that change your working process as a researcher and curator?

Shaffer: I think it will still be possible to do research on or curate works of independent cinema, though the process will be much more direct—I will be forced to contact the makers directly for their work, rather than going through the organizers of festivals/archives.

Cong Feng is a Beijing-based documentary filmmaker. Cong Feng shared a video with me that he recorded on the opening day of the Beijing Independent Film Festival this year, when festivalgoers were confronted by a group of what appeared to be plainclothes and uniformed law enforcement officers and hired thugs outside of the Li Xianting Film Fund’s courtyard-style offices, where this year’s festival was set to take place.

The video, which Cong Feng has shared to be viewed or downloaded, begins with footage of an unknown man in a dark plaid polo shirt telling the festivalgoers that the event has been cancelled, and to go home. The conflict quickly escalates when an officer in a light green uniform suddenly grabs the cell phone of another festival participant who was using his phone to also record the scene. The following several minutes were very chaotic, and the video image eventually becomes obscured by clothing and bodies, though the sound of beatings, a stream of expletives, and complaints and protests from the crowd are clearly audible. Cong Feng and several others eventually extricate themselves from the scene, but Cong Feng turns and runs back several times toward the place where the confrontation began.

I asked Cong Feng to provide his account of what happened on the opening day of the festival, and to clarify several parts of what he recorded. He provided this report in Chinese, and my English translation follows each paragraph:

丛峰:除了我录制的视频之外,现场还有其他几人录制的视频,比我的视频清晰很多,或许更有助于你了解整个事件,包括胡力夫导演等人拍摄的视频,你可以联系耿军导演(就是这个视频中被殴打的人),他们已经把视频传到了微博和网站上,不过有些已经被删掉了,可以让他直接发给你。我的视频是挂在脖子上的小摄像机自动拍摄的,当时场面很混乱,所以非常晃动。因为这个摄像机很像手机,比较隐蔽,所以没有被打人的这些人发现。

Cong Feng: In addition to the video that I recorded, there are videos much clearer than mine that were recorded by a few others, and which might have been more helpful to your understanding of the event, including videos by filmmaker Hu Lifu and others. You can contact filmmaker Geng Jun, who was the man being beaten in the video, as they’ve already put their videos up on Weibo and other websites. However, a few have already been deleted [by authorities], so you can ask them to send you their videos directly. Mine was shot with a small camera that was auto-recording while hanging around my neck, and the situation was really chaotic, so the image is very shaky. Because this video camera looked like a cell phone, it was relatively inconspicuous, so it went unnoticed by those who were beating up on others.

丛峰: 8月23号本来是宋庄的北京独立影展开幕的时间,但影展当天被禁止举办,我和很多朋友到达影展开幕的地点栗宪庭电影基金会的院子外面的时候,已经有很多警车、包括写着“文化执法”标志的车辆停在院外,大概估计有十几辆。有一些没穿任何制服的身份不明的人,应该是村子的混混和地痞之类的,也有一个国保,站在院外路口,禁止我们靠近或进入那个院子。我们在基金会外面的路口呆了一会,后来他们过来驱散了我们,说活动取消了。后来我和一些朋友回到我自己的院子里,呆了半小时后,我们准备再去基金会门口看看,这时我把小摄像机打开,挂在脖子上让它自行拍摄。我们回到院子外的路口,这个时间有很多准备来参加的人又开始围在那里,我们在那里只是站着聊天而已。我的朋友周昕站在我身边。

Cong Feng: August 23 was the original date set for the opening of the Beijing Independent Film Festival in Songzhuang, but on the day of, the festival was forbidden from being held… When friends and I were arriving just outside of the Li Xianting Film Fund courtyard, the venue for the festival’s opening, there were already a lot of police cars outside, including some with the “cultural law enforcement” emblem written on them, parked just outside the courtyard, about ten or so. We stayed at the intersection outside of the Film Fund for while, and then they came over to disperse us, saying the event was cancelled. Then some friends and I went back to my own courtyard for a while, and after staying there for about a half hour, we got ready to go back to the entrance of the Film Fund and check out the situation. This time I turned on my small video camera, hung it around my neck, and set it to auto-record. We got back to the intersection just outside of the courtyard, and this time, there were a lot of other would-be festival participants gathering around the same spot. We were only standing and chatting there. My friend Zhou Xin was standing beside me.

丛峰: 过了一会,the man in the dark green plaid shirt走过来,劝我们离开这里,这个人是谁身份不明。他说完之后刚转身,这时 the man in the lighter green shirt突然扑过来抢周昕的手机,因为周昕用手机拍the man in the dark green plaid shirt,后来知道 the man in the lighter green shirt是小堡村的村长,叫刘中,这个身份基本可以确定,有不止一个朋友这么说。因为他抢周昕的手机,我们都开始指责他并要求他归还周昕手机,这时the man in the dark green plaid shirt走回来,恶狠狠地要教训周昕,我们这边的人和他们的人开始有对抗,很快,他们把矛头集中在耿军导演身上,一下子有好几个人过来把他推到在地,用脚踢,踩,他的肋骨受伤了,但不很严重, this is when someone yells “打人了”,。我和黄香导演把耿军从人堆里从地上拉了出来,尽量让他远离这些打人的人。在此过程中我也被狠狠推搡了一下。

Cong Feng: After a while, the man in the dark green plaid shirt walked over, advising us to leave. Who this man was wasn’t clear to me. After he finished speaking, the man in the lighter green shirt suddenly rushed over to grab Zhou Xin’s cell phone, because Zhou Xin had been using it to record the other man. Later I found out that the man in the lighter green shirt was Xiaopu Village’s police chief, named Liu Zhong—this is basically certain, as multiple friends told me who he was. Because he grabbed Zhou Xin’s phone, we all began speaking up about that and demanding he return the phone. At this point, the first man walked back, wanting to give Zhou Xin some fierce criticism. A confrontation started between us and them, and very quickly they began pointing the finger at director Geng Jun—suddenly a number of people pushed him to the ground, kicking and stomping on him. His ribs were hurt, but not seriously. This was when someone was yelling “打人了” [da ren le! someone’s being beaten up!] Filmmaker Huang Xiang and I pulled Geng Jun up off the ground, to try to get him away from the people who were beating him. In the process, I was also roughly shoved a bit.

丛峰: 这些人继续揪着周昕,威胁要把他带到村委会,我们一直在进行阻止,他们放开了他,但仍旧扣留了手机,并问他手机密码,要删除刚才他拍的照片。我们开始离开现场,向西边村里走,这时仍留在原地的另一个朋友,蜜蜂书店的老板张业宏也被打了两个耳光,好像是因为他买了一些矿泉水给大家喝,这些打人的人要拿走水,他不愿意,这些人就打了他两个耳光。所以我run back,想把他拉走,我们接着向村子里走,这时有个国保喊黄香,让他过去拿会周昕的手机,所以我们再一次run back。然后我们很多人一起离开了现场。

Cong Feng: These people continued pushing Zhou Xin around, threatening to take him to the village committee office. Once we started to make them stop, they let go of him, but still kept his phone and asked him for the password, to delete the photos he’d just taken. We began walking away, toward the west side of the Village. Then another friend who had stayed behind, the Mifeng [Honey] Bookstore owner Zhang Yehong, was also hit several times. It seems it was because he bought some bottled water for everyone to drink, and when the people who were beating up on the others were about to take the water away with them, he wasn’t willing to let them do that, so these people just slapped him in the face a few times. I ran back, wanting to get him away. We continued on toward the village, and at this point a state security officer called out to Huang Xiang, to return Zhou Xin’s cell phone, so we had to run back one more time. After that a whole bunch of us left the area.

I then asked Cong Feng about his personal perspective on the festival and on the state of independent filmmaking in mainland China. My questions, his responses in Chinese, and my translations in English follow:

GC: How has the festival affected your life, personally and professionally?

丛峰: 我2007年开始第一次参加中国国内的独立影展,就是宋庄的纪录片交流周。之后数年,影展好像一个每年固定时间举行的节日一样,让我充满期待:可以展示自己的作品,可以借影展的机会见到很多同行和朋友,可以相互激励,带来新的灵感。所以宋庄影展2011年第一次被停的时候我真的感到很失落。

Cong Feng: In 2007, I began participating in Chinese independent film festivals for the first time, at the Songzhuang Documentary Exchange Week. In the following few years, the film festival has been like a holiday, filling me with anticipation: you can show new work and get the chance to meet up with many colleagues and friends, to motivate one another and find new inspiration. So, the first time the festival in Songzhuang was shut down in 2011, I was really devastated.

GC: Without the Beijing Independent Film Festival, what future do you see for independent filmmakers in China to share and discuss their work publicly? What other resources can filmmakers turn to within China for showcasing their work and finding other distribution opportunities?

丛峰: 在现在的大环境下,大的独立影展或许都不再可能按照前几年的模式继续下去了,需要探索新的集中展示独立电影作品的方式和平台。而且,各地的民间独立放映,小的影展,也都在不断出现,比如天津,长沙等地的民间放映,哈尔滨、大连、杭州等地的民间影展,都在坚持做。还有一些有部分地方政府背景的影展,如西宁的和西安的影展,至少也提供了一些展示作品的机会。

Cong Feng: Under the current circumstances, it’s possible that none of the big independent film festivals will be able to continue operating according to the model of the past several years. They need to explore new methods and platforms for showcasing independent film works. Additionally, independent community screenings and small festivals in various places are continuing to emerge – for example, the independent screenings in Tianjin and Changsha, and other places, and the community film festivals in Harbin, Dalian, Hangzhou, and other places, all of these events still continue. There are also some local government-backed film festivals, like Xining and Xi’an, which at least provide some opportunity to showcase the works.

GC: After previous shut downs of the Beijing Independent Film Festival, I’ve heard some say that independent film in China is “dead” or “dying”. What’s your response to this opinion?

丛峰: 我不这么看。中国独立电影不会死亡,因为有越来越多的人开始拍摄自己的电影,器材很便宜了,信息也很容易获得了,所以从拍电影的角度来说,这个时代恰恰是拍电影的黄金时代。而包括北京独立影展在内的中国几个主要独立影展被叫停或被阻挠,我觉得并没有影响到大家拍电影。影展被叫停,最大的损失我觉得是独立电影变成不成气候了,更被孤立和边缘化了,观众想要知道和看到这些电影的机会更少了,这是最大的损失和影响。

Cong Feng: I don’t see it this way. Chinese independent film won’t die – From the perspective of a filmmaker, this is very much a golden age for filmmaking, as a growing number of people are beginning to record their own films, technology is very affordable, and information is easily accessible. And while several of the major independent film festivals in China have been shut down or prevented from operating, including the Beijing Independent Film Festival, I think this hasn’t at all influenced people’s filmmaking. When film festivals are ordered to shut down, the biggest loss, I think, is that the independent films will lose the opportunity to gain wider recognition, becoming more isolated and marginalized. The opportunities are dwindling for audiences who want to know about and watch these films. This is the greatest loss and impact.

This lost opportunity for the films that Cong Feng speaks of is apparent in much of the media coverage about the festival, in which news of the shutdown eclipses any details of the films. This seems to be in part due to lack of access to the films and film programs after their confiscation by police. However, it’s also possible that general media interest in the story of the film festival’s shutdown actually outweighed interest in following up on the film slate.

Not having visited the festival this year, it took me several weeks before I was even able to find a list of the festival’s selected film synopses. I’d initially sought to find an existing PDF of the program, but festival coordinator Wang Shu reported that all of the digital versions of the festival’s programs had been taken with the festival’s confiscated computers and hard drives, and that there were only some hard copies of the program books left in Beijing. Ultimately, Zhou Xin, a New York-based independent curator and writer (you’ll remember him from Cong Feng’s account), returned to the US after attending the festival and was able to lend me his copy of the program. You can read Zhou Xin’s report on the festival for IndieWire.

Over 80 short and feature-length films were selected for the 11th Beijing Independent Film Festival, within competitive and non-competitive sections. Films were programmed within the categories of documentary, fiction, and experimental film (including animation), along with special sections devoted to works from the Philippines, a showcase of two related documentary works by Japanese filmmaker Kazuhiro Soda, and a curated selection of video art about sensory experience from filmmakers based in Asia, Europe, North America, and Africa.

Programmers for this year’s festival included Ma Li, Qiu Jiongjiong, and Wang Libo (documentary), Liu Jiayin, Yang Chao, and Wang Hongwei (fiction), Pi San, Tan Liqin, and Zhang Haitao (experimental), Gertjan Zuilhof of the International Film Festival Rotterdam (Filipino film program), Nakayama Hiroki (Kazuhiro Soda documentary film program), and Zhang Haitao (Five Senses International Video Art program).

Jury members included Guo Lixin, Wu Wenguang, and Yang Lina (documentary), Nai An, Wang Xiaoshuai, and Yang Yang (fiction), and Li Zhenhua, Wang Chuchen, and Zuo Jing (experimental).

Those invited to lead forum discussions at the festival included Dong Bingfeng, Guo Lixin, Zhang Xianmin, Zhang Haitao, and Gertjan Zuilhof.

You can view a scanned reproduction of the entire program here, shared courtesy of the Beijing Independent Film Festival and Li Xianting Film Fund.

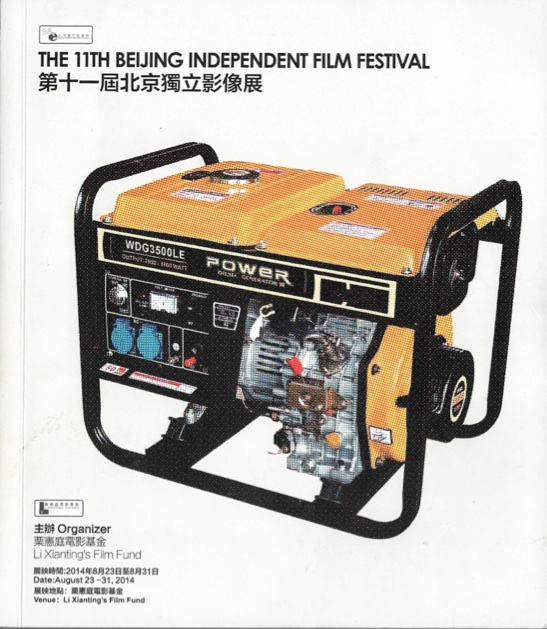

The cover of this year’s festival program book is of a power generator, a playful reference to a previous year when the festival’s electricity was cut off on opening night. While some might see this is as anti-authoritarian, a power generator could also be viewed as a strong symbol not of opposition, but of a steadfast and optimistic alternative. No matter what the fate of the Beijing Independent Film Festival, there’s still a strong conviction that independent filmmaking in China will continue to survive the limitations of any one institution, official or alternative.

The following people made this article possible: Li Shanshan, Cong Feng, Benny Shaffer, Wang Shu, and Zhou Xin.

Regions: China