“The Profession is Crowded Now”

Extra Girls, Scandal, and the Solidifying Economy of 1920s Hollywood

Kerry McElroy’s second series installment of Bette, Marilyn, and #MeToo: What Studio-Era Actresses Can Teach Us About Economics and Rebellion, Post-Weinstein

At a moment in which the structural inequalities and exploitative power relations of Hollywood are being laid bare on a daily basis, it is more important than ever to trace exactly how economics led down this path in the Hollywood film industry. The first essay of this series explored how Hollywood was not, as a layperson might assume, born a capitalist patriarchy, but became one. In the era of the New Woman and the suffragette, Hollywood in fact seemed for a brief moment to offer a kind of utopia for women. Yet sometime in the 1920s, the system of masculinist hyper-capitalism closed like a vise around the city and industry. Ominous forces began to come into play—thousands of women migrating west went from being seen as an exciting promising cultural phenomenon to a social problem that needed to be regulated. The casting couch became, at this time, an entrenched industrial practice. An internationally famous, watershed manslaughter trial- that of Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle for the death of Virginia Rappe- demonstrated exactly the value of women’s lives to the studios. In the midst of these grim developments, there was also paradox—a few women did indeed become massive stars amassing real wealth.

In the later 1910s, the Atlanta Constitution declared that “10,000 girls go to Los Angeles every year ‘to become a star in the movies” (Qtd. in Hallett 145). Cultural historian Hilary Hallett refers to Los Angeles, in this era, as a kind of feminine space; many women arrived seeking careers and independence. Yet a shift from utopian possibility to a climate of poverty, criminality, and exploitation did not take long. Within Los Angeles itself, a type of moral panic formed. In her seminal Babel and Babylon about early Hollywood and its symbols, film historian Miriam Hansen described “the threat attached to the uprooted single woman” (Hansen 235). Discourse in mainstream newspapers began to focus on statistics of women in southern California in terms of both overload and danger. With lurid headlines on vice and crime, Hollywood was coming to be seen across the country as a New Sodom, to be avoided by respectable, unchaperoned young women at all costs.

The warnings to young women to “stay home,” both because Hollywood was a dangerous place and because it was simply too full (for actresses), began to appear in both the American and international press. For their part, the fan magazines used a direct address approach to young women who might be tempted to go to Hollywood and try for the movies. The message and tone changed completely in their address to these readers, from detailing the steps one needs to take to forge a film career, to printing articles of cautionary tales from actresses and telling young women directly to kindly stay home. Magazines scolded the “Movie-Mad Maids” who would inevitably end up at the mercy of the overtaxed Los Angeles social welfare system when they were penniless (Conor 94). The fan magazines also printed interviews and letters from celebrity actresses, telling new young women to be smart and to simply stay away. In an interview with Louella Parsons, actress Ruth Stonehouse said she “felt like telling every girl to stay at home’’, because “the profession is crowded now… it will be survival of the fittest” (qtd. in Hallett 79). The cultural mood was perfectly encapsulated by the titles of two silent films at Warner Brothers over a five year period, starring young Myrna Loy and reaching box office success: 1921’s Why Girls Leave Home, and then 1926’s Why Girls Go Back Home.

More specifically, “the problem of the extra” came to be seen as a social problem for the city of Los Angeles. Studio clubs with den mothers (local, respectable married women) were formed to, at best, give girls a semblance of home and teach them proper etiquette. At worst, the clubs could keep an eye on the women, with the den mothers acting as a kind of matriarchal in-house vice squad. The “problem of the extra” masked an underlying anxiety: the threat of immoral, consensual sex and exploitation in all its many horrifying forms. This included the specific threat of the casting couch. Back to the halcyon days of the early 1910s, the serials in fan magazines had alluded to such problems, in which the girl protagonists were exposed to producer’s advances that they always valiantly resisted. In just a short span of time, these portrayals of rebuffed men and innocent women were beginning to seem hopelessly innocent and from another time. By the 1920s, there was, instead, a new villain—the director—who preyed on the naiveté of young women arriving in Los Angeles with “movie fever.” Los Angeles became associated with a seedy culture that employed schemes like fraudulent acting classes, with bogus and predatory “producers,” “photographers”, and “agents” around every corner. Girls were warned to look out for the man who was a “wolf” or a “movie shark,” but little effort was made to actually protect them.

This was the beginning of a long tradition (one that remains today) where sexual exploitation converged with issues of supply and demand. Too many young and beautiful women vying for the same few jobs meant that their talents and their very individuality were devalued. It also sustained a race to the bottom: who was willing to do sex work to get the job became baked into the system. It was common knowledge that if a woman refused to perform a sexual act, there would be dozens of other women willing. There was no moral protest and no legal recourse—women were explicitly or implicitly told to do what was asked, or someone else would. The casting couch had become an industrial reality. While it did not affect every working actress, it was certainly a standard and abusive practice. In fact and in light of today’s #MeToo moment, we would do well to reframe the casting couch as a working class issue. With an employment crisis of too few jobs for too many women, sex became both an over-inflated currency and a standard industrial quid pro quo. Screenwriter Lenore Coffee declared that “the casting couch was no fiction”, and drew a parallel between the young actress who traded sexual favors for a role and the factory girl who ‘gave the same thing to a foreman to get a better job’ (qtd. in Hallett 150). This recognition of the majority of actresses as both on a working class continuum and far from the glamour of stardom is crucial to understanding the way the Hollywood system developed for women.

In light of the #MeToo, Time’s Up reckoning with Weinstein and a century of Hollywood mores, it is worth asking: why was a squad of matrons needed to police girls and their social behavior in Los Angeles, while male behavior was utterly ignored? The moral panic focused on the women, living in a corrupt city and in circumstances precariously close to prostitution. Panic and outrage was never directed at male actions. Words such as assault, rape, extortion, stalking, and harassment that categorize abuse in this century hardly existed in the early days of film. The fan magazine narratives that alluded to not just overcrowding but moral, economic, and sexual danger utterly ignored that the real problem was the condoned economic and sexual abuse of women by men. These same narratives, like other “women’s media” of the twentieth century, were utterly silent in terms of ethics or justice. The fact was that Los Angeles had become a city that saw the use and victimization of women who came seeking freedom as normal and part of the social order.

In fact, by the early 1920s the system had solidified into what can be defined as a kind of hyper-masculine libidinal playground. The “boys will be boys” attitude of patriarchal misogyny was so deeply embedded in the Hollywood culture as to be sacrosanct. Men were not held to account for their sexual misconduct; rather women were heavily surveilled (for their “protection”) or sent away. Never actually secure, women were frequently cast out while men continued to thrive. Professional, economic, or social consequences for men who abused did not exist. In a culture that used capitalism and respectability as weapons, the onus was on women (not men) to escape sexual abuse.

The pervasive cultural attitude in Hollywood at this time—that male executives could exploit women in a flooded labor system that profited from their bodies and appearance—was bound up in the broader American system of capitalism in the early twentieth century. The mythos of “the captain of industry” led to the valuing of wealth and the hyper-masculine magnate above all. A system of dictatorial male power solidified in the studio system, one that worked in tandem with a devaluing of women’s minds and an increased and fragmented control of their bodies. Indeed, a line exists connecting historical-industrial patterns of this era to the wave of scandals finally breaking in Hollywood and broader American culture today—from Weinstein and Cosby to the pageant-owning and Playmate-paying President Trump.

In light of the scandals dominating the news, a turn to the Fatty Arbuckle scandal of 1921 is instructive. In this case we see a similar confluence money, male power, and sexual abuse. Arbuckle, a slapstick comedian turned millionaire and one of the highest paid actors in silent Hollywood, was in the company of actress Virginia Rappe at a wild San Francisco hotel party after which she fell ill and died. Rappe went to her deathbed accusing Arbuckle of a violent sexual assault that ultimately killed her, while Arbuckle’s camp (including the studio powers that be) mounted his defense in part with rumors of Rappe’s venereal diseases or alcoholic disorders as the true cause of her death. Arbuckle was ultimately acquitted after multiple trials and died a decade later, in poverty and in poor health. In mainstream film history, the case of Fatty Arbuckle’s ruined career has typically been presented as the railroading of a broken man who was unfairly targeted and ultimately died of a broken heart. In light of the current cultural moment, it is a good time not only to reframe this case in terms of power and misogyny, but in terms of economics.

The details of either moral or criminal culpability in Rappe’s tragic death are not themselves central to a feminist re-reading of these events. What is central is the recognition of Arbuckle at the centre of a male power structure, to be defended both as a fellow male and a massive financial asset to the studios. In today’s parlance and the climate of #metoo, we can recognize familiar patriarchal tactics used to impugn accusers and protect wealthy and powerful men. At the trial, Arbuckle was indifferent to the death of Rappe, showing no remorse or sorrow for her death. His lawyers employed a strategy of painting Rappe as promiscuous. Prominent movie colony figures phoned the trial’s prosecutor to suggest that Arbuckle shouldn’t be crucified just because Virginia Rappe had too much to drink and died. After multiple trials and a final forty-three hours of deliberation, the jury voted 10-2 for acquittal and a mistrial was declared.

The Arbuckle case, particularly in the behavior and tactics of the male power Hollywood elite, is a paradigmatic and early example of the studios attempting to cover for male sexual crimes. Arbuckle’s had worth because he had power and money. Rappe did not warrant equal care or value. Even though Arbuckle lost his career, the details of the scandal made clear the direction such cases would go. Women would not be believed, even in death, and the male star commodity would be valued above the non-famous and thus valueless woman. The Arbuckle case can be seen as one of the first glaring examples of white, male power coalescing within Hollywood, a pattern that has continued ever since. In the respect of crimes and cover-ups around women and money, similar cases have happened repeatedly every decade up to the 2010s. Ultimately, the Arbuckle affair serves as a key turning point for the forces of capitalist misogyny in Hollywood.

After a foray into some of these grimmer moments of the consolidating of male power in the 1920s, it is then possible to look to the happier task at hand in this series. While industry control was certainly redoubling itself and male misbehaviors were mounting, there were bright spots. Film scholars today can also identify instances in which savvy women in Hollywood were able to understand the system and the forces working against them, and use these to their own advantages. In some cases, this meant anything from finding the strength to name the system and walk away to actually being able to score financial successes in autonomous ways.

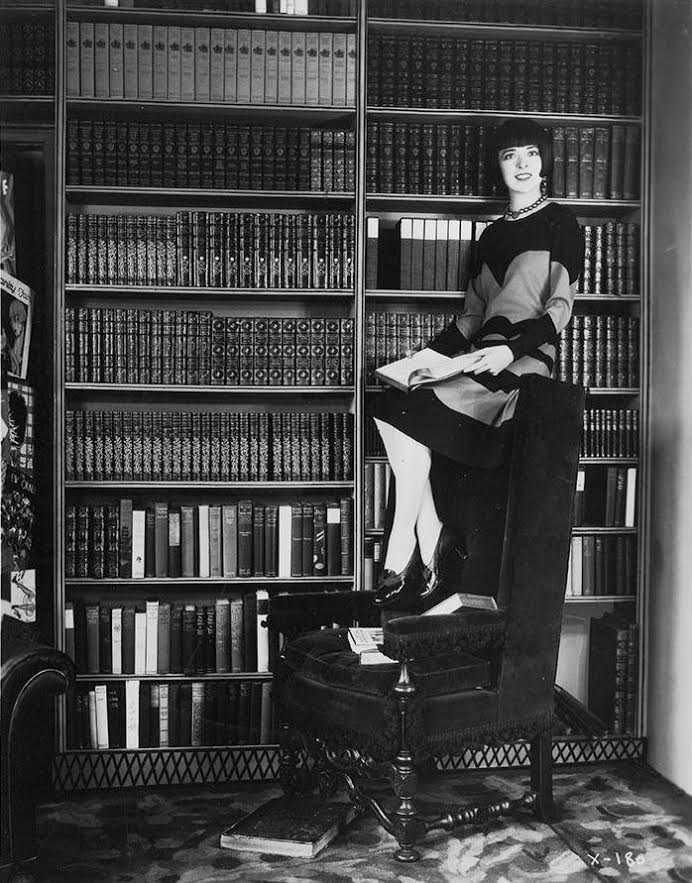

One of the most well-known actresses of the 1920s, Louise Brooks, was able to achieve success against the Hollywood system of a different sort. Even though she spent all of the money she made in film and died in poverty, she achieved an unusual and notable fame later in life as a writer and cinema intellectual in her own right. Though Brooks is today best-known for her iconic flapper hairstyle and aesthetic, it is worth remembering that in her own mind and that of the studio heads, she “failed out” of Hollywood. Yet it is precisely because she didn’t fit well into the Hollywood star industrial economy that she was able to so scathingly indict it it in her writings. Brooks is notable in this case because, both in her life as young ingénue and in her later years as a film critic, she astutely picked up on the predatory, gendered business climate that underpinned Hollywood and articulated it well.

As early as the 1920s, Brooks had already ascertained the Hollywood film industry as a sort of economic system of male-female relations akin to a free-floating brothel. Throughout life, Brooks was fearless in poking holes in the glamour mythos of the dream factory, and in pointing out the ugliness central to the very system in terms of male power, money, contracts, and sexual exploitation. For Brooks, the Hollywood system’s abuses were to be found not just in the auxiliary aspects of production like the casting couch, the amphetamine-prescribing studio doctor, or the mouthpiece fan magazine, but within the labor conditions of production themselves. Brooks was candid and insightful about a system that was designed to chew young women up and spit them out, writing in personal letters (much later in life), “As long as you are young and pretty and willing to be used and abused, they will lead your hope and feed your vanity while they destroy your vision…” (qtd. in Wahl 56). Nothing Brooks identified as to the exploitative capitalist nature for women in Hollywood would be out of place in an interview even today in the 2010s.

In the rather bleak picture for bodily or financial autonomy painted by both the Arbuckle trial and Brooks, are there any bright spots to be found for women in the 1920s, perhaps in terms of economic success or independence? Absolutely. As much as women were being stripped of power and given second class citizenship in Hollywood, this was also an unusual era of wildly inflated, tax free salaries. For this highest upper echelon, gender would have been less of an impediment economically speaking, even as abuses or disrespect might have come in other ways. Those with good business sense, good managers, or both could find themselves set up for life. Some even parlayed film careers into entrepreneurship with high levels of success. These women were the exception to the rule in a Hollywood that was destroying the lives of a good deal of young women, both sexually and financially.

Some of the women who made economic successes of themselves in the booming 1920s consciously looked to the models of those suffragette pioneers of the 1910s who had come to Hollywood in a more woman-driven era. Gloria Swanson, who amassed great wealth in her own right, spoke in her autobiography of having the 1910s silent star and production company developer Clara Kimball Young as a model (Hallett 15). Others were able to use the Hollywood system to transcend their own working class origins to become wealthy, a trend that would continue with the majority of the female stars through the 1930s and 1940s.

A particular star of the 1920s who, like Brooks, understood the gendered capitalist nature of Hollywood, but unlike Brooks used it to her advantage with business savvy was Colleen Moore. Moore’s story demonstrates how occasionally women really did find power in the system through autonomous finances. In later life, Moore wrote an autobiography, Silent Star, and the more explicitly women and business-themed How Women Can Make Money in the Stock Market. The latter book, in particular, has some surprisingly strong and feminist economic salient points for what was marketed as a light self-help book. Moore explicitly wrote the finance book to guide women into what she identified as this world of men. She had two stockbroker husbands for forty years. Moore began to learn about money when her husband insisted she know how to invest her income and gave her a personal finance course. But this volume does not champion the finding of a kindly, rich, businessman husband. It instead includes some deeper salient and even proto-feminist points on women and capitalism. In it, Moore made the excellent point that men, who have long had their affairs managed by female secretaries, were always telling women, who long managed the home, that they were incapable of understanding business . Further, in the book’s digressions into her career as film star, Moore alludes to just how much women were a part of the Hollywood economy. In both her life and observations, Moore is situated in a long but rare line of actresses who were smart to get out of this bad system and take charge of their own affairs by marrying well, investing, or both.

Thus the 1920s were a decade of contradiction in Hollywood—the death of the earlier matriarchy brought the normalization of the systemic abuse of women even as opportunity for wealth and success could be found by a relative few. In the next article, we’ll see parallel trends continue. The 1930’s (where this series will move next) saw both the studio system in peak Fordist condition, and the most famous women stars of the twentieth century negotiating it in new ways. Women like Mae West and Dietrich went to bat for new models of self-ownership and won, attaining international stardom in the process. Bette Davis and Olivia de Havilland, as the article will reveal, left major marks on the history of women’s independence in Hollywood through some of the first court battles around contracts—watershed moments that are particularly worth revisiting today.

References

Conor, Liz. The Spectacular Modern Woman: Feminine Visibility in the 1920s. Indiana University Press, 2004.

Hallett, Hilary A. Go West, Young Women!: the Rise of Early Hollywood. University of California Press, 2013.

Hansen, Miriam. Babel and Babylon: Spectatorship in American Silent Film. Harvard University Press, 1991.

Moore, Colleen. Silent Star. Doubleday, 1968.

— How Women Can Make Money in the Stock Market. Fawcett, 1971.

Wahl, Jan. Dear Stinkpot: Letters from Louise Brooks: or, My Education with Lulu. BearManor Media, 2010.