Clipping the Wires Off the Sapling in Ema Ryan Yamazaki’s Koshien: Japan’s Field of Dreams

“Dedicate every moment of your life towards the team’s victory.”

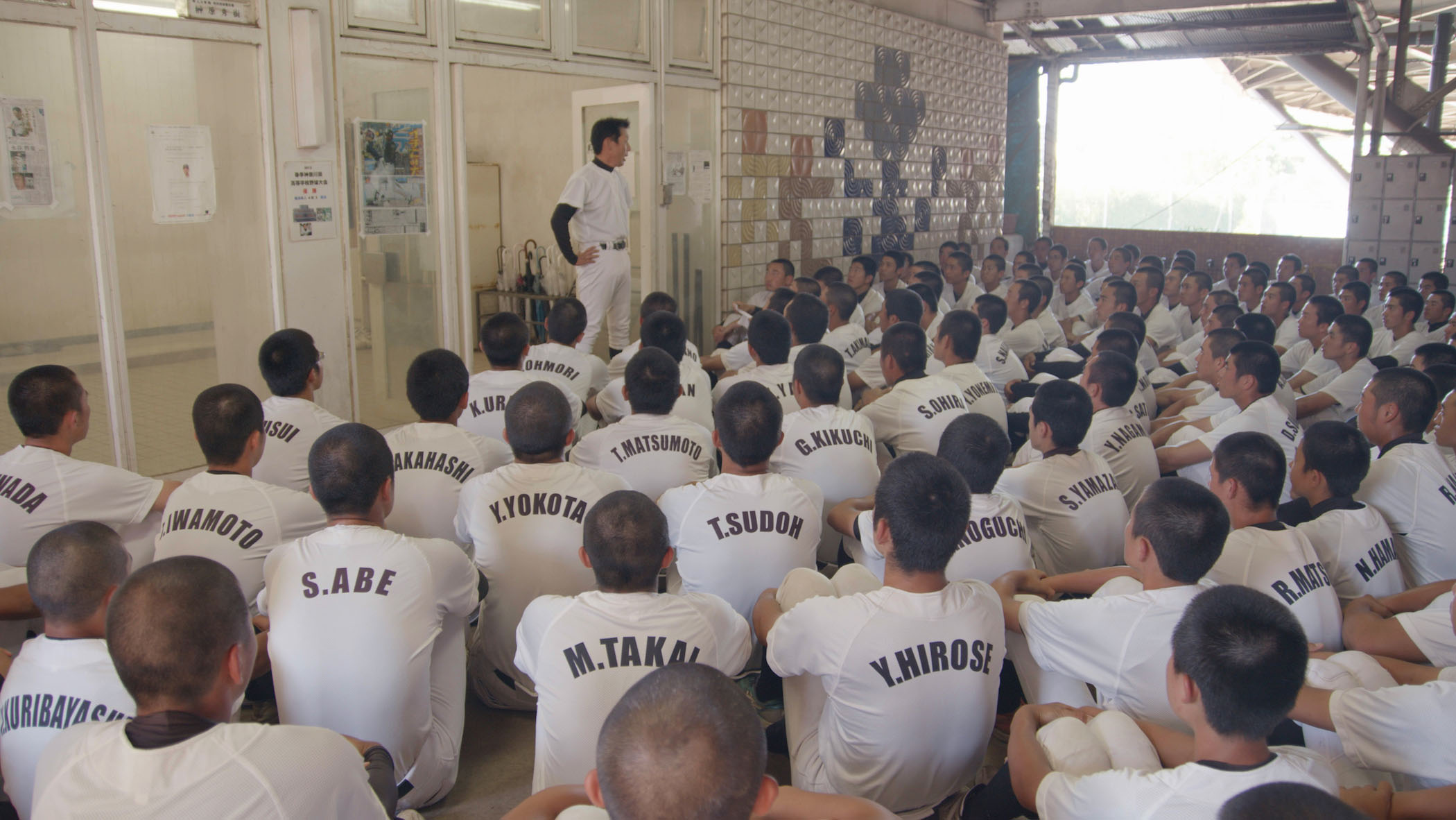

129 teenage boys sit huddled closely together, the air thick with silent anticipation—like a pack of wolves awaiting their alpha’s next command. They hang on each and every word that comes out of head-coach Tetsuya Mizutani’s spirited rallying cry. He is the operator in chief of Yokohama Hayato’s high school baseball team, and it’s almost time for their endless hours of practice to be put to use. For they, along with 4,000 other teams in Japan, have been rigorously preparing themselves to do whatever it takes to reach the holy grail of tournaments: Koshien.

Director Ema Ryan Yamazaki’s 2019 sports documentary “Koshien: Japan’s Field of Dreams” builds an intimate window into the public and private lives of two flawed, but contagiously passionate Japanese high school baseball kantokus (coaches). The film picks up on the eve of Koshien’s 100th anniversary, capturing not only the palpable drama leading up to one of Japan’s most beloved annual sporting events, but also spotlighting the complexity of social debates surrounding antiquated tradition.

Mizutani, an archetype of the strict-natured old-school, has an infectious charisma about him; his pep-talks so invigorating, anyone could run through a wall after hearing one. His philosophy values the many traditions of the sport—one of which requires players shave their heads as a display of the team’s united hearts. For without waterboys and the die-hard support of bench players, there would be no star pitcher, and certainly no victory.

A few hundred miles north of Mizutani lies Iwate Prefecture, where Hanamaki Higashi coach Hiroshi Sasaki whips his promising squad into shape under a different instructional approach—one that likely formulated in spite of a grueling four-year assistantship under Mizutani himself.

An enigma of sorts, Sasaki prefers to spend what little free time he has tending to a garden of bonsai trees adjacent to his baseball diamond; a pastime from which he has gleaned many nuggets of wisdom, sometimes transferring them directly into his on-the-field strategies.

In one especially candid moment, Sasaki ruminates over the prosperity of his former pitcher—now MLB superstar—Shohei Ohtani. Instead of claiming Ohtani’s success as an attribute of his own guidance, he humbly wonders how many pitcher’s careers he may have haphazardly derailed beforehand.

“There are so many plants that I killed by forcing them into my own small pots,” he says solemnly as an image of a potted tree comes on screen—its branches ensnared in metallic wires meant to aid growth during its early stages. The wires are designed to be removed at a certain point—something which Sasaki says he was only recently made aware of. They cause nothing but suffering if left on, thwarting the tree from blossoming into adulthood.

Historically speaking, it’s hard to argue against Sasaki’s bottom-line, with his methods producing a remarkable nine trips to Koshien’s coveted grounds. Take that in comparison to Mizutani’s measly single trip in his almost three decades of coaching, and the upsides of Sasaki’s unconventional ways become impossible to overlook.

This tangible result of the film’s juxtaposition between Mizutani’s espousal of seemingly bygone 20th-century values, and Sasaki’s belief in balancing authoritative oversight with autonomy lends an enlightening multi-dimensionality to Yamazaki’s carefully thought out microcosmic parallel. One that mirrors a rapidly evolving Japan: where tradition is kept intact while working in-tandem with the demands of globalized values.

The same conundrum is found at the center of films like the controversial 2009 Academy Award-winning exposé documentary, “The Cove.” A blatantly Western-centric film, “The Cove” depicts the brutality of whaling practices in Taiji, Japan, without any remnants of an opposing viewpoint on the matter. The film skews its audience’s view of the tradition to such a propagandist extent, that it prompted a more even-handed response film from Megumi Sasaki in 2016, titled: “A Whale of a Tale.”

“The Cove” elects to ignore the historical grounds behind the custom in favor of shock value fear mongering, and in doing so, paints Japan as a place of unchecked cultural relativism. The filmmakers blissfully disregard the idea of balance that is emphasized in “Koshien.”

With the amount of industry accolades that “The Cove’s” ethnocentric, bad faith propositions collected, it underscores the need for filmic conversations about Japanese culture to be led by voices like Yamazaki’s.

Following her graduation from NYU’s undergraduate film program, Yamazaki spent nine years living in the US; a time frame where she worked as an editor on CNN’s docu-series “Chicagoland”; as well as “Class Divide,” an HBO documentary on gentrification in Manhattan’s West Chelsea neighborhood. Following a fully funded crowdfunding campaign for her first feature, “Monkey Business: The Adventures of Curious George’s Creator,” Yamazaki received backing from NHK, Japan’s national broadcaster, when making “Koshien.”

Tapped into both American and Japanese culture, Yamazaki was able to return to Japan in 2017 with a singular ‘insider-outsider’ understanding of culturally specific topics like those brought to attention in “Koshien”—an attribute which allowed her to bring an unprecedented nuance to this century-old event. Through this perspective, Yamazaki challenges and complicates the type of globalized myopia on display in films like “The Cove.”

Executed with a ravishing sense of poetic empathy for her thoughtfully picked subjects, Yamazaki turns a clear-cut story about a baseball tournament into a provocative parable: casting a benevolent, warm glow upon the question of how to keep tradition alive in the face of a rapidly changing progressive landscape.

After premiering at DOC NYC in 2019, the film reached U.S. audiences for a one-night event on ESPN on June 29, and is set for a virtual theatrical release on Nov. 20.

Regions: Japan