I, Daniel Blake Review

Putting a Face to the Faceless

Governments often treat their dependents with callous indifference. They reduce citizens struggling to meet their most basic needs to statistics in order to shirk responsibility for their suffering. The moving indie drama I, Daniel Blake spotlights this inhumane treatment of poverty-stricken people. More importantly, it personifies those who are failed by the institutions created to protect and serve them.

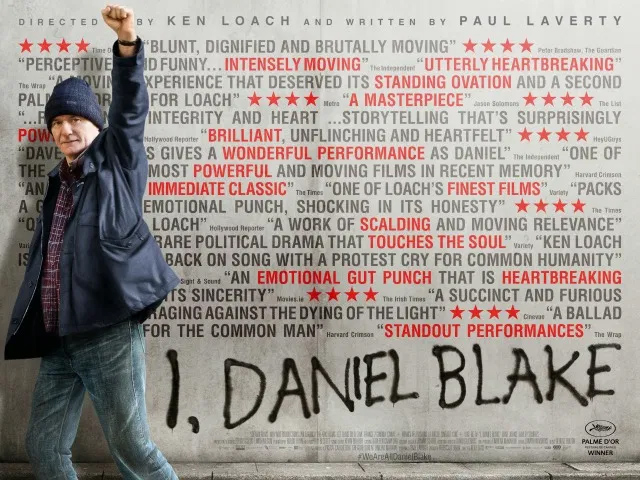

Five years ago last month, I, Daniel Blake made its debut at the Cannes Film Festival. The film, which was written by Paul Laverty and directed by Ken Loach, went on to receive 38 award nominations from various festivals, of which it won 30. Most notably, it took home the Palme d’Or at Cannes and the Outstanding British Film of the Year at the British Academy Film Awards. Not only that, but Dave Johns won Best Actor at the British Independent Film Awards for his portrayal of Daniel Blake.

The film takes place in the United Kingdom, and it follows a 59-year-old man named Daniel Blake who decides to fight the government for his employment and support allowance after surviving a heart attack. The story itself is fictional, but the plot is based on real stories from UK citizens who waged similar battles against the Department for Work and Pensions.

Loach sets the tone for the film from the opening scene by employing a j-cut to isolate a government employee’s voice as she asks Dan inane questions about his physical ability. In this way, Loach emphasizes how this institution also depersonalizes its representatives so no single individual has to take accountability for their actions. In fact, the woman concedes that she isn’t even an employee of the British government—she works for an American company appointed by them.

Despite his determination to receive his benefits, Dan is foiled at every turn. He’s computer illiterate, so he’s forced to ask for help from multiple people just to fill out a basic online appeal form. Also, he waits on hold for hours just to speak to government representatives who inevitably say they can’t help him and redirect him to other reps. As this demoralizing cycle repeats itself, Dan gets buried in bureaucratic jargon that sounds intentionally dense. No one with whom he speaks can provide any answers—they just refer to “decision makers” who will determine Dan’s fate without even meeting him. Worst of all, Dan’s persuaded to apply for unemployment benefits even though his doctor deemed him unfit for work simply because a federal test said otherwise.

Laverty peppers the film with black comedy that reveals the hopeless humor inherent in the backwards logic that governs this system. It’s laughable how someone like Dan, who clearly qualifies for assistance, cannot get the help he needs without wading through an ocean of red tape. Also, as his young neighbor China explains, the federal employees who run the endlessly frustrating bureaucracy are incentivized to discourage those seeking benefits. The more miserable and confusing they can make the process, the more applicants will give up, saving the government money.

But in the midst of his seemingly unwinnable war, Dan still takes time to help a single mother named Katie (Hayley Squires) care for her two children. The loss of his wife and his interminable dealings with the government invoke a bitterness in him, but his compassion and generosity shine through as he bonds with the young family and becomes a surrogate grandfather. Katie embodies the working-class people who are penalized for misfortunes beyond their control, and she must make unthinkable sacrifices just to feed and clothe her kids. Thankfully, in her most humiliating moments, Dan sticks by her and reminds her of her dignity.

Daniel Blake refuses to compromise his self-respect even if it means going off benefits altogether, and that nobility is what makes him so memorable. In his most triumphant moment, he reclaims his name from the government and puts a face on the invisible working class. He’s not a number—he’s a real person who made real contributions to society and deserves real help.

The ultimate injustice occurs in the film’s final scene, demonstrating the gravity of government’s negligence. However, there is no tonal shift because Loach never coddles the viewer in this film. Instead, he presents this harsh reality as it is, leaving the viewer to wonder how such a system might be reformed, or if it needs to be rebuilt. Loach remains almost invisible throughout the story, using very little editing or sound effects. That documentary-like style works because it emphasizes just how bleak life can be for the working poor in the UK. In the end, the film’s abrupt and somber conclusion evokes uncomfortable questions, which is the mark of powerful and impactful cinema.