“Fuck the World!” and the Queer Anger of “The Living End”

As Jack Kerouac prophesied in “On the Road,” the cult classic American road trip book, “The Living End,” directed by Gregg Araki in 1992, starts with one of those characters, one of the mad ones, those that “burn, burn, burn like fabulous yellow roman candles exploding like spiders across the stars.” Introduced to the tune of “Godlike” by KMFDMD, Luke (an HIV-positive drifte), collides with Jon (a recently diagnosed music journalist) setting off on a nihilistic journey into the horizon. In a homage to the Beat generation that plays into the fantasy of Bonnie and Clyde, Luke’s murder of a homophobe and a cop drive the couple to the highway as they run away from everything.

However, “The Living End” does not remain static in the spectrum of road trip movies. From lesbian criminals to heterosexual psychos, Araki holds everyone hostage in this high energy camp journey through the dissolution of American values and its hypocrisy. The director uses a variety of strategies throughout the film, but one scene in particular represents this diversity quite well. In the scene in question, Luke sleeps with a married man that gets murdered by his wife when she finds them in bed: the artificiality of the light, the focus on the knife descending and later the blood montage come together as a way to expand the genre of the road trip movie. Where the genre can have shock and mayhem, Araki dramatizes it in favor of humor and excess, rather than the individual and internal journey of its classic examples. Through different references to Hitchcock, to Coppola’s “Apocalypse Now,” and, of course, to queer culture, Araki manages to expand the usual road trip language beyond self-discovery.

In many senses, “The Living End” exaggerates queer existence by relying strongly on its stereotypes, a treatment that every single identity faces through the movie. Homophobes take the shape of irrational cartoonish monsters, the doctor who gives Jon his diagnosis makes the typical over-the-top shaming regarding sexual practices, and Darcy exists as the hyper-involved bisexual friend. Jon characterizes himself as “I’m a fag, I like to be clean,” and Luke represents the classic hyper-macho gay stud. In this framework, Araki demands artistic freedom not only to go full camp but also to use it as a political weapon.

As such, “The Living End” represents a rabid indictment of the Reagan and Bush administrations and their hand in the genocide of a generation of LGBTQ+ people, but through a language imbued with camp panache. It chooses to channel this anger through nihilism and pleasure. Not through hope, which never enters the script—Luke chooses freedom precisely because he’s “doomed”—but a genuine pleasure of existing, being on the road, and choosing to abandon a society that has abandoned you first. In a notorious scene, Luke lays on top of a car, gun in one hand, crucifix in the other, fantasizing about killing Bush, or even better, injecting him with his own HIV-positive blood. In the scene, Jon is horrified, and when Araki was asked about the scene years later, he found it surprising. Yet, the rawness of the queer anger that the narrative exudes is precisely what has remained unique and fresh about it.

In all truth, the premise comes off as deceptively simple: Luke and Jon go on the run in 90’s America after Luke murders a cop. Clearly, the effect does not remain quite as linear. Around the 1990s, several of the most compelling and humane AIDS plays had already been released, “The Normal Heart,” “Angels in America,” but none of them had reached the big screen in a notorious way. The few that had (“Long time Companion,” 1989; “An Early Frost,” 1985) were primarily dramas that left no space for the playful but raw depiction of queer experiences, not to mention anger. As opposed to the reduced emotional framework present in those films, “The Living End” discomfits, plays around, and carouses with its viewer. Its violent streak and melodramatic tone play with different genres to create a work of art that reflects the camp spirit without losing any of its political edge.

Nonetheless, that anger does not reside in the characters themselves. Luke spouts a series of beliefs regarding AIDS: that it’s a Neo-Nazi Republican solution, that the people of his generation are the “victims of the sexual revolution,” that since he’s going to die, he might as well be free. He shares these ideas carelessly, convinced but largely unconcerned. The frankness and jocularity in the discussion of AIDS—when Jon reveals his status to Luke before they have sex, Luke answers, “Welcome to the club, partner”—was unprecedented at the time: this character had chosen to abandon any sort of responsibility to society, to simply ride his pleasure and drift through life. Direct and political anger had no space in him, or at least not in a constructive, “democratic” way. Rather than the characters themselves, the script, the art direction, and the editing express that anger in a political manner.

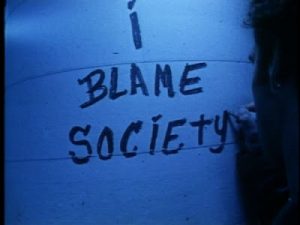

The art direction of the movie does consistent work in this regard, as well as the colors and lighting. Not only do we find car decals, graffiti, and imagery that defies the system, but the characters themselves create it. The famous “Fuck the World!” tag that opens the film sets the tone of much of the graffiti Luke draws, as he tags “it’s society’s fault” and modifies homophobic tags in public bathrooms. These elements provide commentary on the events and emphasize the nihilism at the heart of its characterization, like when Jon receives his diagnosis and drives away, the camera panning to a decal in the back of his car reading “CHOOSE DEATH.” The attention to detail and the time the camera spends on spaces become vital to the feeling of speed in the story; saturation inhabits it in every sense.

The chiaroscuro of the sex scene when they first meet and the sexual tension amongst the very geeky decorated space of Jon’s room intentionally set this environment. It constructs an ambiance of freedom and darkness, almost “doomed love” but without flinching away from sensuality, queer sex, and joy. The emotional universe of “The Living End” resembles a rocky landscape, rollercoaster-worth highs and lows as the couple grow apart but increasingly in love with each other. Along the road, Jon and Luke delight in each other, Jon laughingly cutting off a call to Darcy as Luke draws in the phonebooth that they will be together “til death do us part.” Along the road, Jon desperately wants to go home after Luke kills someone yet again.

Ultimately, “The Living End” lives up to its reputation as a hedonistic story. And yet, its artistic decisions and the final note from Araki hold a sense of queer anger that had not been featured before in the mainstream. The viewer is left despondent, in a saturated desert of orange toxic-like colors outlining the characters, foreshadowing the impending doom of Jon’s worsening illness. And yet, what a wild, fun romp it is.

Regions: United States