Emma Varteresian Talks Stop Motion and Her Film Whispers From The Heart of A Rose

Artist and animator Emma Varteresian says, “No one ever does stop motion the same” and her ambitious work proves as much. Varteresian has needle felted, painted, storyboarded, and animated her family’s history transforming it into a stop motion folktale. Varteresian has wanted to share the story of her great grandmother’s exile from Armenia since her freshman year of college. As she puts the finishing touches on Whispers From The Heart of A Rose, Varteresian took a moment to speak with me about her process, her inspirations, stop motion, and Armenian culture. Here is an abridged version of that conversation.

Sara Crepeau: Can you share a little bit about your creative process?

Emma Varteresian: The first year was mainly research based. And I didn’t start doing character designs or thinking about how I would visually express the story until the beginning of last semester. So, in the fall, I started with transcriptions from my great grandma. My cousin sat down and spoke with my great grandmother and then wrote her story down word for word. So all I had was that. And then I fact checked this stuff she was saying. I tried to figure out where the places referenced were now on modern maps versus what she was saying they were then. And then I did a lot of research on Ancestry.com to figure out when she moved here and when she was born. So I could figure out what age she was when her story was happening.

Sara Crepeau: Can you walk me through the typical steps involved in creating a stop motion animation, like where you started to, like, obviously not complete yet, but where you expect completion to be?

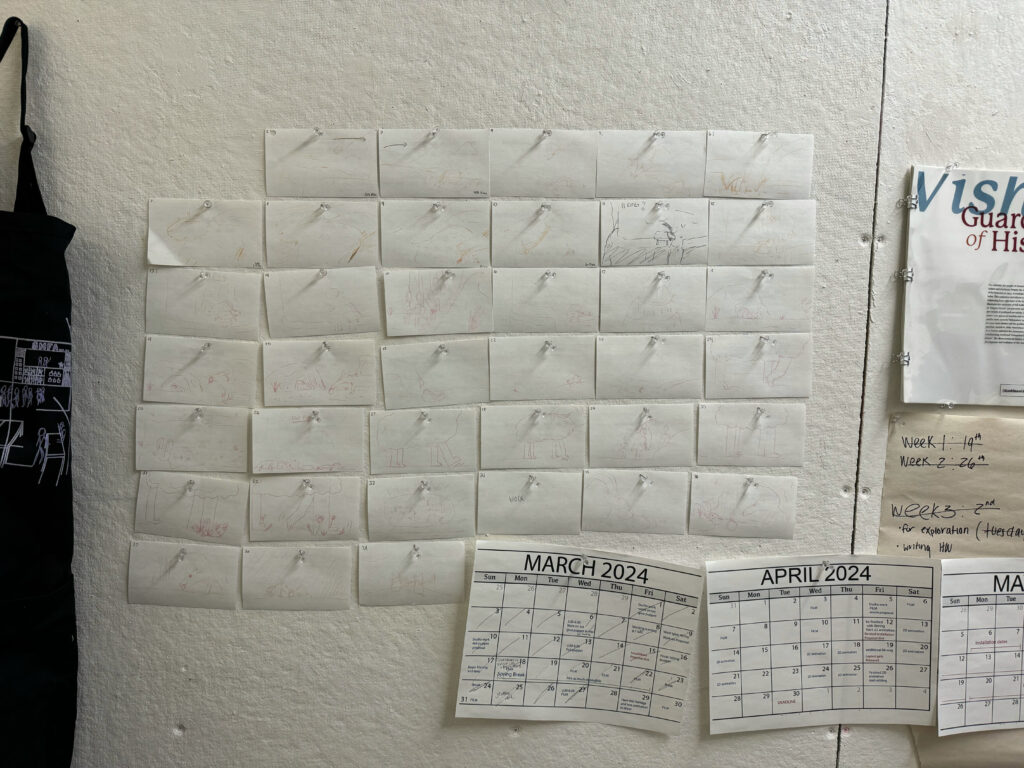

Emma Varteresian: I suppose I started with an idea and then researched and sat with the idea. After that development I started to visualize the characters. And then I started doing the character design. Then I moved on to figuring out the shot list and the order of what is happening. Then I’d storyboard the list, like physically write out everything on index cards. After that I did an animatic, where I took my storyboard frames and I put in some inbetweens, which are just more frames in between each keyframe. It was a smoother way of seeing what the final product was going to look like. Then I had to start working on environment design and what I wanted the environment to look like. I did a lot of research on miniature building, train miniatures, and lighting. I did research on stop motion from individuals and big studios, but it’s really hard to get information about how they do things. They don’t want to share how they do stuff so that other people can do it. I went to MoMA in New York and saw the exhibit Guillermo del Toro: Crafting Pinocchio. That was super helpful because then I could just sit there and stare at how they built the sets and take pictures. And then I made my sets like that. At first I did a test set but I didn’t like how it turned out. So then I moved on to making a second version and I did it way larger. Then I planned it out so that all of my shots lined up with the set and I could shoot from different angles from all over the set and not have to make multiple sets. Do you want me to go into more detail about how I made the puppet?

Sara Crepeau: Yeah, absolutely.

Emma Varteresian: The puppets are built around a mechanical skeleton. Originally, I wanted to do a very simple wire armature with really simple joints that were held together with clay or like that hard cement putty stuff. But because my puppet needed to have four legs and have all of those different joints for the wrists and the goat’s hooves as well as backward joints or elbows and goat legs it wouldn’t be stable enough or strong enough to withstand the constant bending; the wires inside would snap. So during my directed study last semester, I made four versions of the puppet and none of them worked. So, I just decided to do the mechanical one. I bought one online and modified it to have four legs instead of being, like, human shape. Then I had to decide what I wanted the body to be made out of. One of my big stop motion inspirations is someone named Emma De Swaef [https://www.marcandemma.com/about]. She does felted puppets. Everything that she does is felted. And so I wanted that, like, really fuzzy, soft look, to contrast the rocks and the harshness of the set. So I researched how she does stuff. I started with a foam base, and then I needle felted on top of that foam base after I shaped it. Then I needle felted on details. I also used chalk pastels, with a paint brush to add shading on the fluffy parts. It was the same process for the other characters. They have foam inside. I also bought the fur— it was hard to find fake fur— and I’ve just been sewing it onto the body and then attaching it to the foam.

Sara Crepeau: Tell me a bit more about your puppet-making process.

Emma Varteresian: I guess a big part of the planning/making process is figuring out how articulated you want your puppet to be. My puppet has no mouth. I can’t really animate the mouth, but if I wanted to, that would have added a whole other layer of complexity. But my puppet does have eyes that can blink. The eyes I’m going to make with little glass cabochons, like little glass circles with a flat back. I’m going to draw out the little eyeball on a piece of paper and glue the glass on top so it looks 3D. Then I have little felted pieces of the same skin color in eyelid shapes in different stages of being open and closed.

Sara Crepeau: So you can attach those on?

Emma Varteresian: Yeah. And I’m just going to attach those eyelids on with museum putty. It should be easy enough to pull off without it messing anything else up.

Sara Crepeau: Are you adding sound to your film or do you have a score planned?

Emma Varteresian: I don’t think I have time. There’s no dialog. One of the main parts of the film is where the wolf licks a goat’s wound and it heals . After that a little bell appears; a little silver bell on a red cord which is based on an Armenian tradition of wearing a red braided cord bracelet for protection. Throughout the film, the bell is going to ring really loudly, but sound like it’s far away. A lot of the sound effects I’m going to try and do by myself, and if I can’t make them myself, I’ll pull them from free source websites.

Sara Crepeau: That info will be super helpful to everyone who wants to do their own project.

Emma Varteresian: Yeah, I use a lot of different programs but they’re all Adobe. I’m going to use Premiere Pro for editing, Audition for the sound, and After Effects for the background. Then to draw the background I like this drawing software, It’s just a free one, it’s called Krita. It’s more for drawing and you can also animate on it. So all my 2D animation will be done in that program as well. And then everything will be exported as separate files and then compiled in Premiere Pro. The sound will be done in Audition, and then I’ll import the sound as one big file and put that into Premiere. I can just drag and drop all the things into each other and Adobe will recognize it.Then the credits and titles and all that other editing will be done last.

Sara Crepeau: Are there any recurring themes or motifs that you find yourself returning to in your work? Any differences from your first stop motion project to now, or are there any similarities?

Emma Varteresian: In terms of similarities to stop motions I’ve done in the past, the felting,—keeping everything soft looking—is the same. I think I just prefer that aesthetically. I love when you can tell that it’s stop motion, but it doesn’t look like stop motion. It’s like a game of tricking people into thinking it’s something else when it’s not. And then in terms of recurring motifs I would say there’s a lot. The goat is a big motif that recurs because the goat is based off of a very specific breed of goat, the ibex goat, that is native to the Armenian Highlands which is where my great grandmother was born. The goats have a big horn with these ridges. These goats are seen in Armenian folklore as mythical creatures, like divine beings because they’re massive. When ancient Armenians were going through the mountains and they came across this massive fucking goat with, like, massive horns, it’s like, “oh, that’s the forest god or like the mountain god.” So that motif is brought through the whole film, obviously, because the goat is the main character. Then the color red is really important like the red cord and the red on the pomegranates. Then also the pomegranates themselves I use a lot in like my metals work and any of my other mixed media work. A wind chime I did had pomegranates hanging off of it. During my research when I first started this project I came across Armenian vishapakars, which are stone monuments. They’re places of worship for a specific god or a specific goddess. There’s a lot of lore.

Sara Crepeau: You seem to have a pretty good grasp on all your lore!

Emma Varteresian: I think I know the lore. For example, there’s this goddess Astłik who is basically the Armenian version of Aphrodite. She’s the goddess of love, beauty, fertility and so on. Her iconography is the pomegranate, which is also used in Armenia a lot. That goddess has a holiday called Vardavar, which is the ancient version of the modern Christian holiday the Transfiguration of Jesus. But in Armenia, it’s still called Vardavar, or the festival of water. It’s associated with Astłik because she was also the goddess of water. It’s called Vardavar because “var” is the beginning of the word “rose” in Armenian [Armenians offer roses to Astłik during this festival] .

Sara Crepeau: Like your last name!

Emma Varteresian: Like my last name Var-teresian. So, that’s why I like her and her holiday. And one of her symbols, obviously, is a rose. The goat connects to her because the way she was worshiped was through those big stones. And on those big stones were usually depictions of those ibex goats or fish. So, anyway, the goat connects to her because that species of goat is meant to be like the divine version of her. And then, my great grandma in the film is represented by that goat.

Sara Crepeau: There are so many different tiers of information leading up to this Armenian type of goat.

Emma Varteresian: I did a lot of research on what symbols I wanted to use and what colors I wanted to use because I didn’t want people to ask me questions and not to have real answers. Everything in the film is based on Armenian folk magic. Like throwing salt over the shoulder or sucking on ginger if you’re sick, stuff like that, which my family still does. Even though we stopped speaking Armenian there’s some random traditions that we kept for some reason.

Sara Crepeau: That’s so cool. So like, these traditions have persisted, even if the rest of your family don’t necessarily know where they come from. The traditions they’re just so resilient.

Emma Varteresian: That idea of traditions persisting and being resilient is one of the main themes of the film. Because the goat never gives up and she just keeps going. My Grandmother’s story, it’s very gruesome. When my cousin first interviewed her she was really old so you can tell in the transcript that psychologically, she was making excuses for things and being like, “oh, it wasn’t so bad” because if it was that bad, then she believes she would’ve lost it way back then. You can tell from the way that she says things that she knows it was bad, but she doesn’t want to accept that it was bad. She had like five sisters or something and multiple brothers and they all died at some point. She was the only one who survived. My great grandmother walked all the way from Eastern Armenia to the edge of what is now Turkey which was Western Armenia.

Sara Crepeau: So, I guess to finish up, do you have any advice you would give to someone who’s interested in getting started with stop motion?

Emma Varteresian: I would just say just do it. Just try things. You don’t really understand how to do it unless you try to do it and it goes wrong. It’s a very scary big project but just play around. Don’t take it too seriously. No one ever does stop motion the same. Even the big studios don’t do it the same. They hire artists and those artists are experts at what they do. In Coraline, there was one lady who just did the wigs and the hair and that’s her expertise. No one else can,build a wig like she can and she just does it the way it works for her. So, like, everybody does it differently just find your own process!

Whispers From The Heart of A Rose can be viewed in full at emmavarteresian.myportfolio.com