Book Review: “Reappraising Cult Horror Films.”

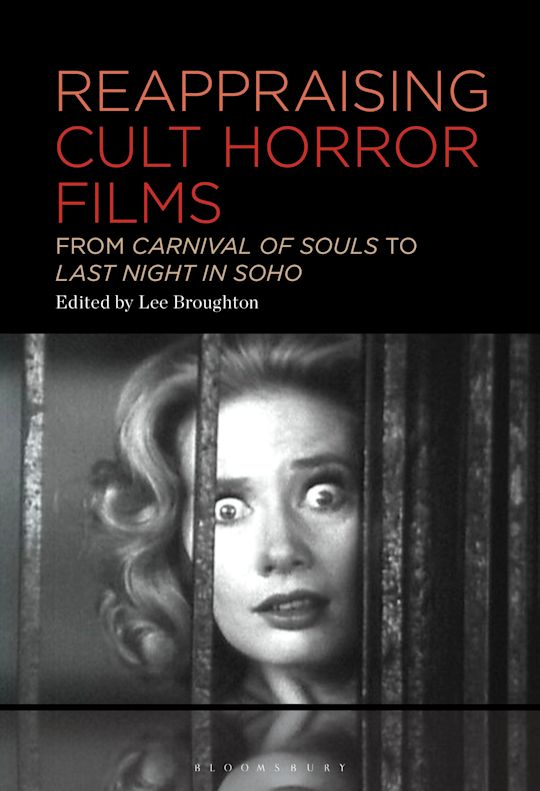

Reappraising Cult Horror Films, From “Carnival of Souls” to “Last Night in Soho”

edited by Lee Broughton. Bloomsbury Academic, hardcover, 288 pages, $108.00. ISBN: 978-1-5013-8758-6

Mention cult horror films to a group of people and each of them will immediately conjure up a different film. Some might immediately think of one or more of the original “Evil Dead” movies. Older movie fans might think back to their video store days and visualize the VHS covers for John Carpenter’s “The Thing” or “Halloween.” Younger cinephiles might immediately think of “Jennifer’s Body.” I immediately think of being a high school kid watching and re-watching 1962’s “Carnival of Souls” and Roman Polanski’s “Repulsion” from a recording of a New Year’s Eve horror movie marathon broadcast. We all have our favorites that we can defend as underrated works of genius.

In “Reappraising Cult Horror Films, From “Carnival of Souls” to “Last Night in Soho,” we get academics do exactly that. The thirteen chapters within the book offer reappraisals of several cult horror films through “critically exploring them from new theoretical and analytical angles or aligning them with similarly themed films…in order to tease out new meanings and insights… that might go some way towards identifying just why these particular films continue to capture the imagination.” Within these chapters readers will be introduced to new films, or in some cases reintroduced to films they have seen a dozen times, but somehow missed the message for the body count.

Lee Broughton’s introduction clearly defines how the book approaches the idea of cult horror films and provides the tendons that keep the chapters together. The first section addresses standalone features of cult horror and begins with “Carnival of Souls.” Instead of giving us more explanation on why this deserves more attention, Bill Shaffer provides production history that explains how this film got made and frames the movies as the paragon of independent horror. Next is a chapter on “The Legend of the 7 Golden Vampires,” a movie that mixes vampires and martial arts, by editor Lee Broughton. From there we climb the mountain of horror movies for a stay at Kubrick’s adaptation of Stephen King’s “The Shining.”. Kamil Koscielski walks us through the well-trod labyrinth of the movie only to point out what most critics and filmgoers have missed in all these year: the strange timeline of the movie dependent not on ghosts but on interdimensionality. The next three chapters in this section investigate the rich tapestry behind the slashing and mayhem of two cult classics and one on its way to becoming one. Cynthia Miller and Tom Shaker reveal the rich cultural references places throughout “Killer Klowns from Outer Space,” while Phevos Kallitsis provides a history in urban planning that’s key to understanding “Candyman.” The last chapter in the section looks at the more recent movie, “The Hunt” and shows how most commentators and right-wing media types completely missed the anti-capitalist message floating beneath the perceived red state boosterism.

The second section broadens the focus out to look at not just a single film, but multiple works by a director. A chapter by Mark Goodall assesses the filmography of Belgian director Jarry Kümel including the films “Daughters of Darkness” and “Maplertuis” and invites the reader to revisit these films to delight in the mix of horror and the surreal. This is followed by Matthew Melia’s re-evaluation of the latter films of Ken Russell including ‘The Fall of the Louse of Usher” from 2002 and Russell’s ‘garage-iste’ philosophy that will resonate with any independent filmmaker.

The last section looks not at a single film or a single director, but at the fixation on place (the US state of Georgia, Australia), culture, and the outsider that guides the narrative of certain movies. The five chapters within this section all reveal the influence of other films and larger cultural movements within the horror genre. Xavier Mendik looks at the movies that ran with the premise of “Deliverance” to give us the white trash trope that has become the core of Rob Zombie’s films. This is followed by a brilliant chapter by Pete Falconer that looks at how Australian filmmakers of exploitation films in the 1970s and 1980s often mixed and matched genres to create something entirely new to cinema. From there we look at twenty-first century French horror and how, according to author Alice Haylett Bryan, we understand them not for what they are, but for the “Frenchness” we see mixed in with the extreme violence of the films. Kev Bickerdale takes us from the gutters of Paris into the high-rises of horror and shows how movies like “[Rec]” and “Shivers” find horror in the vertical. The last chapter brings the reader back to earth with a chapter by James Shelton that looks at how the role of the ‘investigative outsider’ in horror films isn’t always about revealing the horror, but more often about becoming it.

The chapters within this collection will give horror fans new insight into their favorite cult horror films. For the scholar of independent film, the chapters provide important reappraisals that uncover the context that is hiding beneath the buckets of blood and other body parts. For the independent filmmaker, the chapters on “Carnival of Souls,” “Killer Klowns from Outer Space,” Ken Russell, and twenty-first century French horror cinema provide insight on the creation and reception of cult horror through tricks and techniques familiar to all independent filmmakers.