From Mirage to Millions: The 40 Year Journey of the TMNT

Issue One: Turtle Power

Edited by Francisco Viana

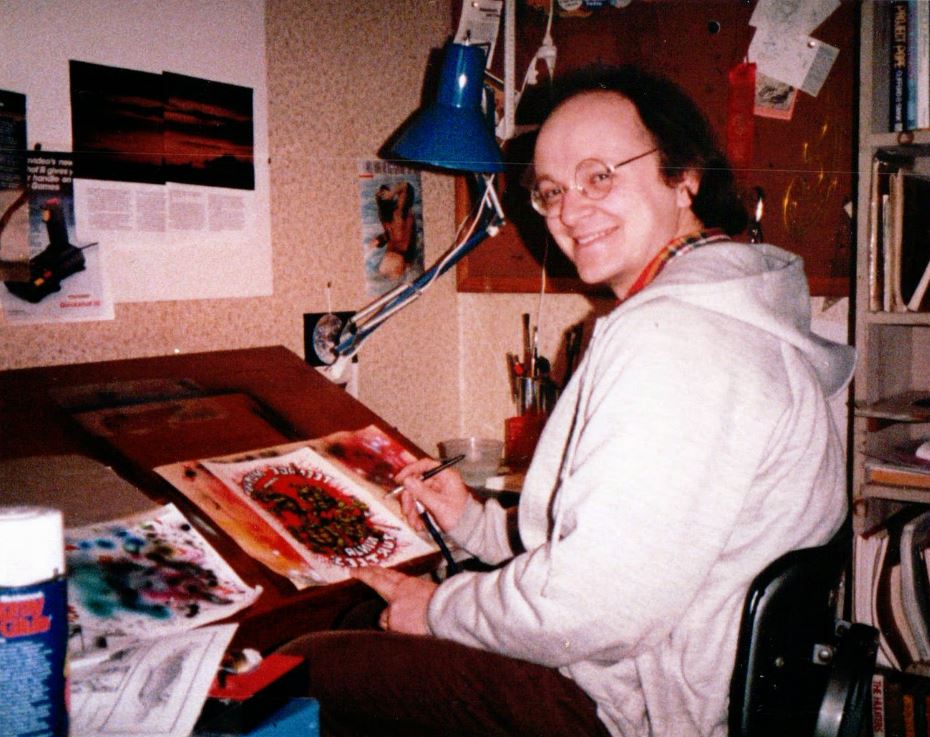

In November of 1983, in the dingy living room of two aspiring comic artists’ New Hampshire home, history is about to unfold. Kevin Eastman, 26, and Peter Laird, 33, are sitting together on the couch brainstorming their next long-form comic. A sketch pours out from Eastman’s pen: a turtle standing on its hindlegs. He adds a bandana, some nunchucks and three more turtles striking dramatic battle poses. Before Eastman knows it, he and Laird are laughing their heads off at these ninja turtles, the prototype of what would become their livelihood for decades to come.

What started as little more than a quick doodle shared between two friends exploded into one of the most profitable franchises in American popular culture. The Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles (TMNT) were a near-instant success. Their popularity came as a shock to the duo, who were unsure whether they would ever earn back the money they put into publishing the first issue. Years later, in 2023, a new addition to the franchise would gross $28 million at the domestic box office during its opening weekend.

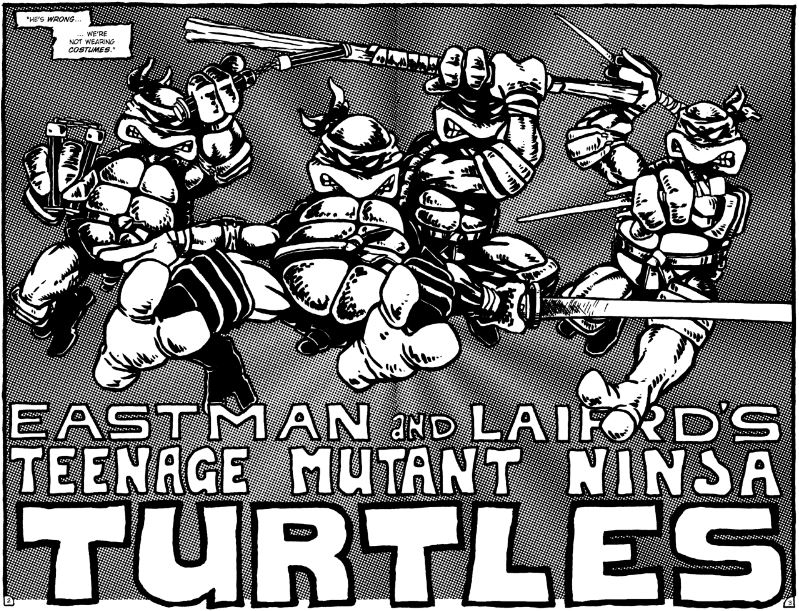

Eastman and Laird self-published their first issue of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles in May 1984. “Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles #1” was a forty-page black-and-white comic published with a tax refund and a thousand dollars in borrowed money from Eastman’s uncle. The only color Eastman and Laird could afford to print was a red overlay for the cover, featuring the four turtles on New York City rooftops in menacing battle stances. After printing their first run, there was just enough money leftover to buy an ad in “Comic Buyer’s Guide,” the American comic industry’s leading periodical. The turtles quickly became the poster child for Eastman and Laird’s independent comic publisher, Mirage Studios, a company named after the fact that there was no physical studio outside of their living room.

“It’s got to be their absurdity that made them popular,” says Bill Cody, the owner of Geek Inc. Comics, a brick-and-mortar Illinois retailer that has been in business for over ten years. “They’re different enough from normal superhero books that it feels like you’re reading something different but it scratches that same itch.”

The core turtles team is composed of four brothers, all of whom are named after Italian figures of the Renaissance Era. Eastman and Laird chose this theme because they thought it would be funnier and more memorable than trying to come up with authentic sounding Japanese names. Leonardo, Raphael, Michelangelo, and Donatello are raised by their adoptive father, Master Splinter, who happens to be a mutated rat-man with expertise in martial arts. Splinter trains his sons in the art of ninjutsu. The turtles defend New York City and the rest of the galaxy with these skills, squaring up against countless monsters, robots, ninjas and aliens.

Leonardo, the team’s leader, is a blue-wearing katana wielder, whose maturity and strong sense of discipline shine the brightest when Splinter is not around to guide them. Donatello dons a purple bandana and acts as Leo’s second-in-command, using his bō staff and affinity for robotics to solve complicated problems for the team. Raphael is a sai-wielding brawler whose wild attitude is matched only by the color of his fiery red bandana. Finally, Michelangelo is a fun-loving goofball, with his orange bandana, scarily fast nunchucks and hidden artistic side.

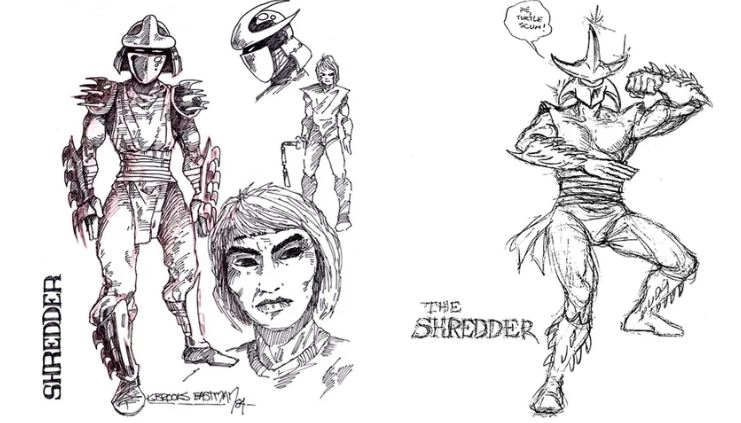

Though the turtles were conceptualized from little more than an inside joke, the ideas were refined into an amalgamation of Eastman and Laird’s favorite comic book characters. For example, the turtles’ origin story is a bar-for-bar parody of Daredevil, a Marvel superhero whose powers were awakened after exposure to radioactive chemicals. Daredevil’s mentor Stick was reworked into the turtles’ Master Splinter, and the supervillain organization known as the Hand became the turtles’ number one enemy, the Foot Clan. The Foot Clan’s leader, however, has a much less glamorous origin, as Eastman and Laird have admitted to designing the Shredder’s samurai armor with little more than a cheese grater in mind.

“People in the know looked at the first issue and saw all the nods to the early ‘80s Frank Miller comics ‘Daredevil’ and ‘Ronin,’ but Eastman and Laird really made TMNT their own thing right away,” says Andrew Farago, curator of the Museum of Cartoon Art and author of “Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: The Ultimate Visual History.” “They were influenced by their heroes and their contemporaries, but they knew they had to build something beyond that if the series was going to last.”

“TMNT” #1’s release coincided with a much larger shift in the dynamics of the publishing industry. The mid 1980s signaled the end of the Bronze Age of Comic Books, an era characterized by flux within major comic publishers and a rapidly evolving market. Within Marvel and DC, the two most prominent publishers at the time, many veteran writers were moving on from their grunt illustrator positions. Several figureheads within the Big Two, such as Jack Kirby and Mort Weisinger, were either retiring, earning promotions to management positions, or hopping over to the competitor’s side. These changes in power sparked the rise of small-print self publishers like Eastman and Laird.

As smaller, more diverse publishing companies found their footing in the eighties, the manner in which comics were distributed underwent a complete transformation. Comic books moved away from being cheap mass market products hawked at every checkout aisle at the grocery store. The Bronze Age market was characterized by an increase in specialty retailers that sold higher quality products to narrower audiences. Suddenly, comic readers had a reason to accumulate hoards of whatever new issues grabbed their attention.

One major factor contributing to the turtles’ initial success was their desirability among collectors. The first few issues of “TMNT” were printed as an oversized edition that resembled magazines more than traditional comic books. In addition to being printed on larger paper, the issues were twice as many pages long as the average comic book from Marvel or DC.

Due to their small print run of only three thousand copies and the widespread transition away from disposable mass market comics, the turtles were instantly sought after by collectors. A few months after “TMNT” #1’s second print run, copies of the first printing were resold for up to twenty times the original cover price.

These issues became even more coveted following Mirage’s “Guest Era,” a twenty-two issue period in which the ninja turtles were exclusively written and illustrated by creators outside of Mirage’s regular staff. Not only were the original issues small in quantity, they were also becoming a smaller and smaller percentage of the work that Eastman and Laird actually collaborated on together.

By 1987, TMNT had reached the height of its popularity. They had recently licensed the turtles to Palladium Games as playable characters in their tabletop roleplaying games. Reprints of old issues were averaging about 125,000 sales each and Eastman and Laird were revered as local legends in the indie comics scene. One night, the duo received a call from an unknown number. On the other line was the head of Playmates, a small California based toy company that would change the turtles’ legacy forever.