Why Robert Eggers’ ‘Nosferatu’ is a Horrific Movie Beyond its Gothicism

When Robert Eggers’ “Nosferatu” came out on Christmas day, thousands of people packed into movie theaters across the country to watch the modern rendition of the classic vampire tale, buttery popcorn resting atop jeans and black draping gowns. After a day of opening presents and spending time together, my family and I sat among the eager gothic fans at our hometown theater on opening night. But by the time the end credits rolled and the lights turned on, I couldn’t shake a deep feeling of discomfort at what I had seen, a reaction I quickly realized was not shared by most audience members.

Having had months to process the film, I now know why I felt this way. While the film’s cinematography is undeniably gorgeous and the actors’ performances are impressive, the movie’s ending sends the message that women cannot surmount their sexual shame and trauma, propagating the idea that they must submit to a destruction of self for “greater peace.”

Before I elaborate, here is a brief synopsis for those who haven’t seen the film:

Nosferatu, a 300+ year old vampire, answers a call for companionship from Ellen, a despaired young woman grappling with loneliness and desire in Wisburg, Germany in 1838. The two develop an intimate relationship that turns manipulative and parasitic over time. When Ellen settles into a genuine and loving marriage with real estate agent Thomas Hutter, she begins to feel Nosferatu’s presence again. In an attempt to reclaim Ellen, the vampire takes Thomas prisoner, sets loose a plague and subjects Ellen to psychological abuse and fits of terror from afar. As the torment worsens and Nosferatu kills Ellen’s friend Anna, alongside her two kids and her unborn child, Ellen begins to consider the deal proposed by the vampire: to sacrifice her life and love in exchange for the salvation of the town and everyone she loves. With everything at stake, Ellen is pressured to submit herself to Nosferatu for the “greater good.” In her final act of life, knowing Nosferatu cannot resist the temptation of her body, she exploits his desire for her in order to distract him until sunrise when the sunlight destroys him forever.

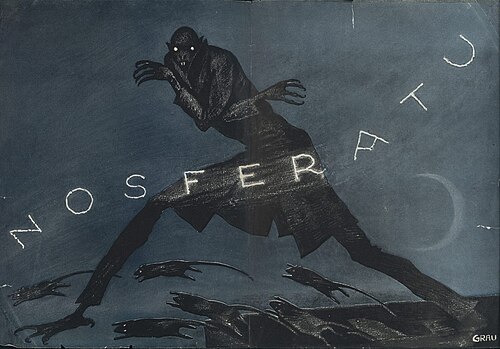

It is important to note that the 2024 film is an adaptation of the original “Nosferatu,” a German silent film made in 1922 by F. W. Murnau and inspired by the novel “Dracula” by Bram Stoker.

Though Eggers stays true to the original plot and characters of Nosferatu (as well as iconic images, like the hand shadows) he pushes the story in a different direction by centering themes of sex and desire, ultimately changing the message of the movie with its morbid ending. Eggers’ adaptation is not the first to interweave these themes with a vampire’s violence and insatiable thirst; we see these elements in the original Dracula novel and in Francis Ford Coppola’s famous “Bram Stoker’s Dracula”, however both of these works end with the death of the vampire allowing the woman to live a life of her own, free from terror. Robert Eggers’ does not follow lead, his screenplay ends with the death of its female victim.

In the 2024 rendition, Nosferatu becomes the materialization of Ellen’s sexual shame and trauma, a metaphor that is made explicitly clear when Ellen says, “[Nosferatu] is my shame! He is my melancholy! He took me as his lover then, and now he has come back . . . He stalks me in my dreams.” Ellen indicates to us, the audience, that Nosferatu is not only a disgusting vampire, but a symbol of oppression.

When German director F. W. Murnau’s “Nosferatu” was made in the 1920s, a social revolution was happening in Germany: women were seizing their right for emancipation. During this decade the “new woman” emerged: a figure who had power over her actions and body, who had autonomy and who embraced the bold act of taking up space. This social change permeated Murnau’s film. By attributing Nosferatu’s death and the village’s resulting survival to Ellen’s sacrifice, she became a heroic woman with rare agency seen in the media of this time period. Through this ending Murnau challenged the “damsel in distress” trope of the Gothic genre, giving his female character autonomy and power in the mid 1800s, a time when women were considered mothers or housewives, and nothing else.

Eggers’ decision to change the main theme of the movie from a fear of the unknown to sexual desire, sexual shame and trauma without changing the ending completely alters the movie’s message. Instead of representing a woman with agency and earned respect, Ellen’s death at the hands of her sexual shame spreads a message to larger audiences that women cannot surmount their sexual trauma and guilt.

The perversion of Eggers’ ending becomes even more clear when Ellen’s sacrifice is not merely of blood, per a classic vampire tale, but instead through the forced consent of physical and emotional submission. In the film’s final scene, Nosferatu engages sexually with Ellen and she dies beneath him. Considering Nosferatu stands as a symbol of Ellen’s shame and trauma, the film communicates that a victim of sexual manipulation, trauma and shame cannot overcome their oppression or oppressor, and the only way to alleviate the pain caused by these experiences is to submit to death or a complete destruction of self.

The problematic and frankly abhorrent narrative is further pushed by Ellen being blamed for Nosferatu’s violence. In his screenplay, Eggers writes: “I [Ellen] have brought this evil upon us . . . I sought company, I sought tenderness, and I called out . . . At first it was sweet, I had never known such bliss. Yet it turned to torture, it would kill me” (p. 87). By making this addition, Eggers places Ellen at the center of the problem, solely responsible for having brought Nosferatu upon her town. Thus she “must” make amends by giving herself away as the final solution.

In the film Professor Von Franz, the occult scientist philosopher, tells Ellen that one “must know evil to be able to destroy it.” He continues by stating that once a person discovers the evil within them, they “must crucify the evil within us, or there is no salvation” (p. 105). Ellen responds that she has done no ill, but “heed my nature” (p. 105). Through this exchange, the male character paints female desire as something evil that must be purged and shamed. Von Franz actively blames Ellen, the victim of the abuse, for the violence committed by her abuser, a harmful narrative that persists through Ellen’s death.

Some argue that the narratives in the film are a reflection of the time period during which the work was born in and the story takes place, however Eggers’ “Nosferatu” was made in our time period and misogynistic tropes should not be excused. Beyond this, the original “Nosteratu” was set in the same narrative time period and was made 100 years ago, yet Murnaux intentionally worked to counter this sexist gothic trope, successfully making a frightening gothic movie while sending a message of female power and agency.

Even in our post–Me Too culture, Eggers’ “Nosferatu” works against these ideals and instead shifts the narrative to push an oppressive message. When analyzed more closely, the insistence on blame, shame and exploitation of the female body, through added components by Eggers, is a direct affront to women’s sexual autonomy and power.

With this message coursing under the surface of the film, I sat in my movie theater seat horrified, for something other than the movie’s gothicism. If Eggers was willing to change the core theme of the original movie, he could have changed the ending of the film to retain its original message, or at least avert a harmful one. Filmmaking comes with a high responsibility to tell stories with care and promote humanity, especially to the audience it is meant to serve. It is unacceptable to promote messages like this in the 21st century, or at all. In our time, despite the source material, Eggers has a responsibility to understand the impact of the messages in the original novel and Coppola’s film, and make the appropriate edits, exactly like F. W. Murnaux and Henrik Galeen (screenwriter) did in the 1920s Nosferatu!

Eggers’ “Nosferatu” was nominated for multiple accolades and received a lot of praise from horror fans, film critics, and general audience members alike. Even so, it is important to see beyond the marketing, aesthetics and acting, and examine the potential impact the film has through the harmful message it perpetuates.

Regions: Boston, Los Angeles