David Lynch’s ‘Twin Peaks:’ Anglo-Saxon Folklore Wrapped in Plastic

In formalist and interpretive film histories, David Lynch’s “Twin Peaks” has been dubbed as one of the few popular postmodern works portraying psychosexual exploitation within a seemingly serene environment. In the series, which originally premiered in 1990, Lynch applies and manipulates a proto-traditional Western outlook on typical abusive patterns to produce critical commentary regarding the illusion of innate security among one’s own.

The show centers on the sudden murder of virtuous, infallible high school student Laura Palmer in the town of Twin Peaks, Washington. In the pursuit of finding Palmer’s killer, spectators discover Twin Peaks not as an aspiration, but a cerebral veneer hiding its fair share of secrets.

This quintessential lack of a “grounding” in the midst of surrealism and eccentricity is a defining characteristic within postmodern-era film and television, and Lynch’s series is no different. Instead of defaulting to the reaction- and resistance-oriented streams of postmodern artistic technique, “Twin Peaks” loosely adopts postmodern conceptions of both reaction and resistance. It is a series that is both constricted and constructed by social context and privileges articulated by the series’ exposition, and embodied by its characters.

Conventions of social hierarchies and structures within the female category place Laura as something of an ‘Alpha Girl’ to the Twin Peaks universe. On the condition of network television, Palmer was conventionally attractive, wealthy, popular and, of course, blonde.

“David’s work isn’t consciously coherent, but its coherence on an unconscious level is inescapable — almost against your will,” Michael J. Anderson, who played The Man from Another Place in “Twin Peaks” said. Dean Valentine, then-president of the United Paramount Network stated that the main problem of network television was that there were “too many ‘Friends’ clones — urban, affluent, white, twenty-seven-year-old yuppies who just want to get laid. Most of America doesn’t fit that bill,” Valentine said. Lynch’s reactive-resistant approach to this archetypal figure appears indirect on the surface, with the perception of Laura Palmer becoming less black-and-white as the series progresses.

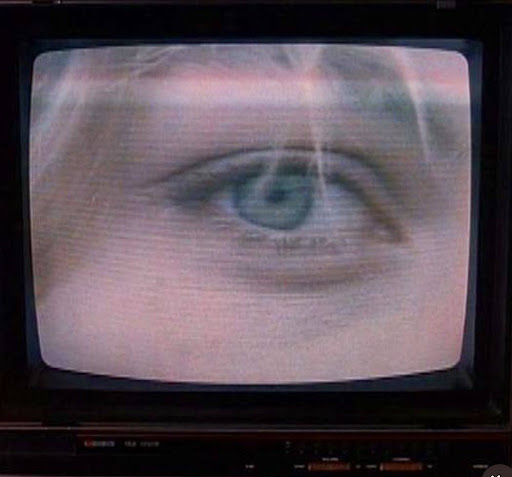

“Twin Peaks” is a work simultaneously cohesive with and critical of its target audience. The show intentionally does little to differentiate the narrative from the setting, forcing the audience themselves into a state of tension between nature and reality. In the audience’s perception, nature is a benign place, bound only to unregulated physical and behavioral patterns, enveloped by an intrinsic darkness. After Laura’s death, a town-wide search party was conducted, and the forest was the one place Special Agent Dale Cooper didn’t look, because it was the one place where she wasn’t idolized.

Although often associated with “pure beauty,” blonde hair has historically retained a dualistic denotation in Western culture. Blonde hair symbolized lust and weakness, and simultaneously represented something sacred and powerful, akin to a supernatural quality. Highlighted throughout the series are Laura’s various excursions into the unrestrained forests of the Pacific Northwest, which are masked with ambient coloring and distorted uses of light and shape, all deliberate actions from Lynch. The distorted imagery of the forests with the celestial imagery of Laura composes an almost meta futuristic oppositional force to the implicit anxieties to viewers: both predator and prey, Laura Palmer was the ultimate postmodern paradox.

Twin Peaks was considered a cerebral environment by its outsiders, but follows a view rather prevalent: physical beauty is aristocracy. Lynch knows this, taking account of Laura’s overtly Germanic racial characteristics, mostly her blondeness, bridges an ontological gap between conception and reality that emulates shifts in the Anglo gene pool. The concept of blondeness as both a passive and celestial motif was conveyed throughout Anglo-Saxon mythology and folklore. From the “adorned golden tresses” of Eve in John Milton’s “Paradise Lost,” to the sorocide in 17th century Scottish ballad “The Twa Sisters,” in which a blonde woman is murdered by her dark-haired sister, and a harp is made from the strands.

In 1863, Victorian ethnologist John Beddoe published an article in the Anthropological Society stating light hair is becoming less of a dominant feature that is slowly becoming “fazed out” by dark hair. Beddoe alleges a population-wide change in Teutonic and Nordic gene pool, attaching “great importance” to ontological depictions of Anglo-Saxon features. These findings evolved into folktales, creating something of a hyper-legend standing tradition evolving from throughout the Germanic imagination. The myth is as follows: if a blonde woman is murdered, her hair rises out of the grave to expose her killer.

The very first images we see of Laura herself are of her hair, peaking out of the plastic before she is properly identified as Laura Palmer. Lynch, in his dreamlike shots of Laura’s excursions into the forest, satirizes this symbolic position by disacknowledging it artistically. Considering Laura is one of two steady characters to have blonde hair (the other being Double R Diner owner Norma Jennings) along with her perception, the series on a superficial level confirms the notion that blondeness is a signal of class, meant to inspire aspiration. The aspiration itself was never the precise act of going blonde, but the idea of a teenage girl possessing the sociosexual capital to do so. Lynch knows this, and the people of Twin Peaks affirm it. The locals know Laura, the desire that surrounded her, and the forces who wished to control it. Laura Palmer functions ideally as a character that operates within a certain racial and socioeconomic position whilst holding a space in Twin Peaks that was subversive and submissive at the same time.

One’s perceived attachment to the established Plathian, archetypical, alpha-girl imagery of Laura Palmer displayed by her blondeness is not just subverted but completely destroyed towards the end of the series — when her killer is revealed. A sexually abusive spirit known as BOB possessing the form of Laura’s father, Leland. Leland’s displays of BOB’s position are purported early in the series — the former frequently breaking into song, dance and tears, not in sadness but in guilt. The disturbingly surreal and poetic space “The Black Lodge” becomes Laura’s home after being killed in which we see tears, a display of vulnerability in response to being harmed — an authentic but very much gendered sense of agency that was seldom present in her life. We know she made choices that ultimately were not trumped by her displays of perfection and security, the exploitative motives and systems decided this for her.

Regions: Boston