Reclaiming the Male Gaze: Learning to See Through Film Photography

Every culture shares the way it sees and understands what is beautiful. These standards vary enormously from one society to the next, and they change over time. But one aspect remains the same: Men control these standards.

Men have always observed and transformed the female form into static representations. Sculptures, sketches, paintings, anatomical studies, fashion lines. This act of creation — and ownership — is “the male gaze.”

Seeing is different than gazing. Gazing starts with seeing, then enters a process of observing, perceiving and, finally, creating. This process transforms what one sees into an artifact. Though the artifact exists freely and separately from its maker, it’s entirely dependent on the perception of the gazer.

Sometimes these artifacts are remembered for centuries as blueprints of feminine beauty, mystery and intrigue. Think: da Vinci’s “Mona Lisa” or Botticelli’s “The Birth of Venus.”

These global representations of feminine beauty can be considered a form of censorship. As one artifact of the female form becomes popular, it gains dominance. Simultaneously, other representations are forgotten.

Our senses can also become censored through repeated exposure. When the images we perceive conform to an unquestioned standard, we must question if the standard has become our standard.

When you make the effort to see and feel for yourself what is beautiful, you will inevitably push against the confines of the status quo. We have been trained to expect a degree of normalcy and conformity, all of which can begin to fall away as we reclaim our ability to observe, perceive and feel. We combat the male gaze by developing our own gaze.

I’ve questioned my own gaze for years. As a small child, I observed my three sisters — triplets eight years older than me — become women, and marveled at the power, allure and dynamism in femininity. Simultaneously I saw men lie, cheat and be violent in their reach for women. And I’ve gazed at myself in the mirror, watching my perception of self shift from day to day. My own perception of myself is as capricious as the winds, rising and falling with my mood, my cycle, the day’s events.

If how I perceive myself is that unstable, how varied is everyone’s perception of the other? This shifting instability — of how I and others perceive beauty — became my study.

And so I started experimenting.

With my film camera, I used motion and blur to express the infinite ways a human can be seen, depending on who is doing the seeing. Maybe — by visually representing this instability — something more palpably stable could emerge.

The beauty of film photography is that when I’m behind the camera and she is in front of it, I press a button, the shutter releases and the film is exposed. *Click.* But the image we create together remains invisible. It must be developed after the entire roll has been shot.

Shooting film is a process that takes time. In the moment, the artifact’s lack of visibility allows the person behind and in front of the camera to remain close and grow closer.

With a cell phone or digital camera, the image is immediately available. With film, the connection between who is behind and in front of the camera comes first. The act of observing and perceiving is continuous, uninterrupted.

–

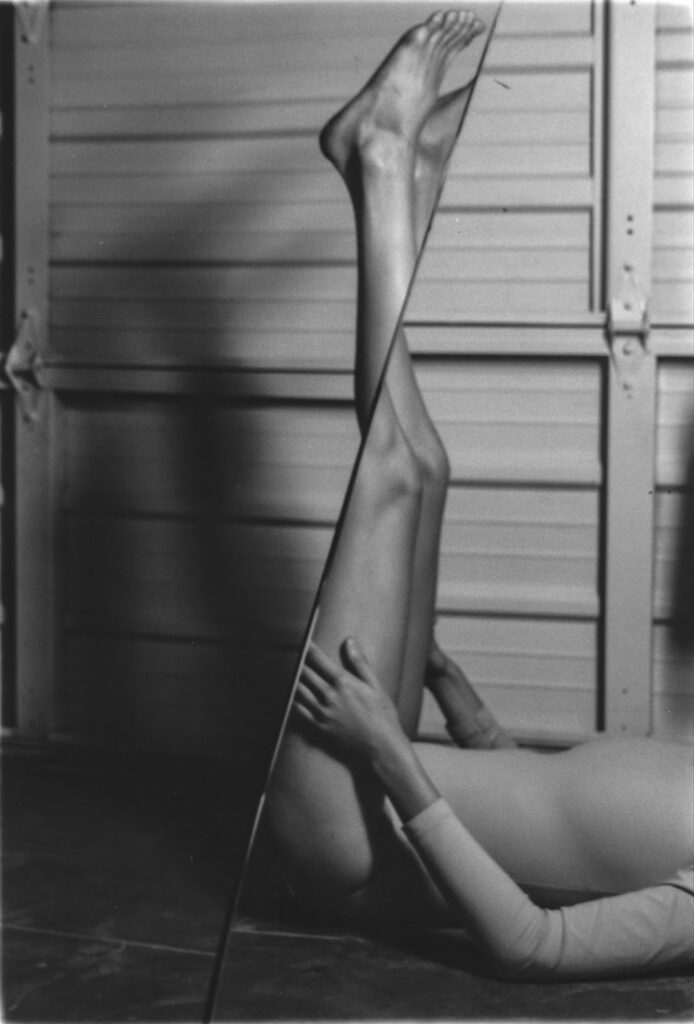

I lived in Los Angeles from 2015 to 2016, working as a food caterer for Hollywood movies and TV shows. I drove all over the city. One day I saw a huge mirror standing against overstuffed trash cans, waiting to be picked up. Down the mirror ran a long, thick crack. It was beautiful.

I asked my dancer friends to pose; I wanted to explore the suffocating, unrealistic body standards that LA — the epicenter of global entertainment — thrives on.

I visited my sister in California’s East Bay. I was outside and she was in the kitchen, and the moment I saw her through the screened window, I saw the living representation of our separation. Two women sharing so much of the same experience, yet so completely different. The screen suddenly embodied our supreme tension — the intimacy of our relation intensifying the expanse between us.

After a year, I left the underground LA art scene to pursue something more wholesome and lucrative. Working in the world of black market cannabis, I traveled to and lived on various rural, off-grid farms. I witnessed the juxtaposition of wild forests and agricultural cultivation. I questioned the ways we control nature’s image to produce the desired effect for our consumption, and I saw the parallels to my ongoing exploration of feminine beauty standards.

Cannabis — used recreationally and medically — is a flower that grows only on the female plant. The evening before harvest, in a field full of ripe women, I joined my image with theirs.

I continued to explore the wild and cultivated qualities of plants and nature by exploring female sexuality through double exposures.

Next was the bathroom — a place of intimacy, cleansing transformation and self-observation.

Over several years, I perceived my own image in these spaces, using different means to represent the barrier of the object (body) and subject (the one who gazes).

The barrier: A sheer, ripped lace curtain.

The barrier: A steamed bathroom mirror. Could I capture the softness I see in femininity through this haze, their reflection, our intimacy?

I am not a static object of beauty. Neither are you. I’ve experimented with visual distortion, symbols and barriers to explore and represent my experience of beauty as malleable, variable and alive. The male gaze can be questioned. Beauty as we see and feel it for ourselves is waiting to be reclaimed.

Regions: Portland