Sundance 2014: Three Films Disturb the Peace

Neil Kendricks on the cinematic raconteurs that stormed Sundance 2014.

Park City, UTAH — Rocking the boat is practically a pastime for the most adventurous films at the Sundance Film Festival, which turned the big 3-0 this year. Robert Redford’s annual indie film oasis served up a sporadically subversive, all-you-can-see buffet, delivering jolts of smart storytelling and provocative themes—if you knew where to look.

Sure, Hollywood’s more commercial aspects have gained a considerable foothold at Sundance in the wake of the festival’s three decades of existence thus far. This year was no exception as star-driven vanity projects in search of street cred rubbed shoulders with their more left-of-center counterparts in the New Frontier, Documentary, and Shorts programs. For these larger films, screening at Sundance is a pit stop on their way to would-be domination of your local multiplex, the on-demand market, or both.

Even though part of Sundance has become a victim of its own success, this essential 10-day showcase of independent film still makes room for wonderfully spontaneous and offbeat movies. Festivalgoers craving a true alternative found cinematic eruptions of creativity and risks spearheaded by filmmakers who delight in their refusal to play well with others. In this respect, Sundance still provides a forum for much-needed cinematic troublemakers who make it their business to run against the grain of our expectations with surprising results.

A case in point is Jim Jarmusch’s welcome return with his new film Only Lovers Left Alive that delves into vampire mythos without using the shopworn words “vampire” or “undead.” This quiet, introspective film is sure to have its detractors. The Ohio-born filmmaker’s deliberately slow pace and signature, minimalist style will make some critics want to drive a stake through the unapologetically literary heart of Jarmusch’s latest, cinematic, tone poem. For the film’s niche audience, however, this odd and strangely trance-like film is a tonic, embracing good books, music and culture rather than caving into the more visceral tropes of the horror genre.

In fact, Only Lovers Left Alive is more of a melancholic love story about a married couple at odds with their environments than your usual vampire romp of flashing fangs and bare necks. Both Adam (Tom Hiddleston) and Eve (Tilda Swinton) pine for yesteryear when they were in their prime and the world was full of promise. But the dark world that they inhabit is riddled with decay and emptiness. Adam kills time driving through the desolate, nighttime streets of Detroit while making stops at a hospital to buy blood from a corrupt doctor (Jeffrey Wright) at a local hospital. Likewise, Eve spends her time in the narrow passageways and bazaars of Tangier, trading playful verbal spars with Christopher Marlowe (John Hurt) who refuses to acknowledge that he wrote Shakespeare’s greatest works.

Needless to say, Twilight’s rabid fan base should steer clear of these intellectual vampires who love poetry and the Motown sound since none of these creatures of the night “sparkle” nor do they mutter nonsensical declarations of chaste love. Instead, Jarmusch’s bloodsuckers are a more heady lot that are cognizant of the fading glory of the Old World with its ripe and succulent pleasures. They are well-dressed ghosts haunting derelict streets in a new century when poetry and pop music with soul have all but vanished. The film blossoms into a quiet lament for the bygone pleasures of the analog world where the smooth textures of vinyl records and the interior music of literature speak directly to the heart.

Ironically, this movie is the first time that Jarmusch worked with a digital camera to make a movie. His images still retain their soft, warm glow that you find in his other films as this analog storyteller ventures into the brave new world of digital filmmaking with no regrets.

Only Lovers Left Alive fits in perfectly with Jarmusch’s ongoing body of work that explores and deconstructs genre tropes. His mise-en-scene slows down the stripped down narratives of his films to a crawl. The defiantly independent filmmaker, best known for 1984’s Stranger Than Paradise and 1989’s Mystery Train, does this in order to take stock of the small details that are usually ignored in most films by emphasizing speed and fast cuts; the barrage of dazzling visual effects are hardly an adequate Band-Aid for movies too often lacking in good stories. If you share Jarmusch’s idiosyncratic point of view, Only Lovers Left Alive stays with you, lingering in the memory long after the final credits roll.

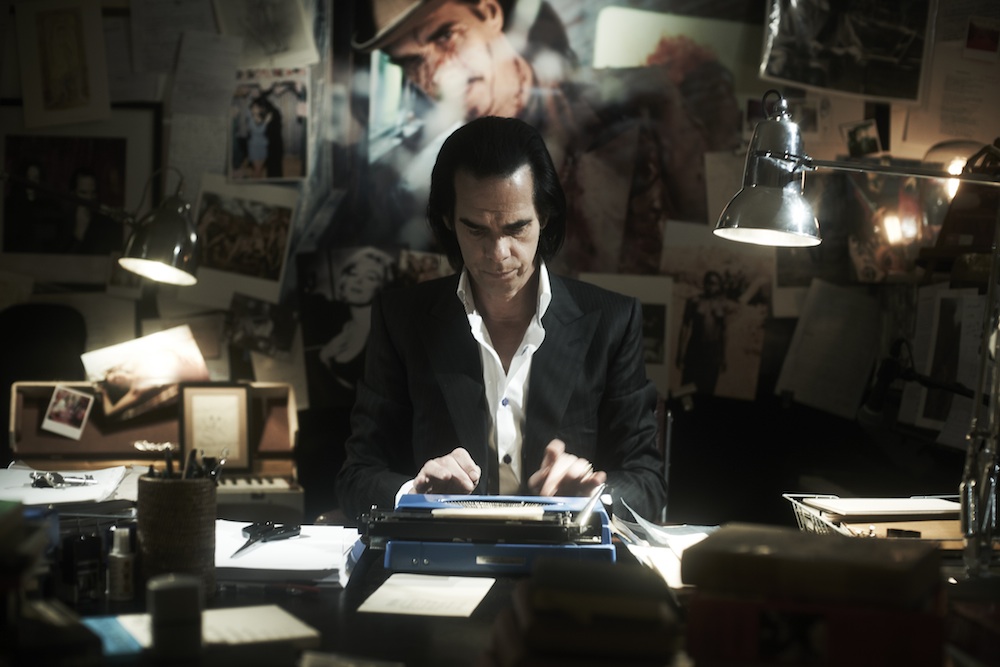

Jarmusch’s neo-gothic romance could make a great double feature with Iain Forsyth and Jane Pollard’s award-winning documentary 20,000 Days On Earth. It had its world premiere at this year’s Sundance. Adam and Eve are soul mates cut from the same cloth as the documentary’s main subject, singer-songwriter Nick Cave whose voiceover opens the film with the declaration, “at the end of the 20th century, I ceased to be a human being.” Of course, Cave is being facetious in his claims since his haunting music is all about the difficulties and challenges, the terrors and triumphs of being human. His running monologue juxtaposed with Forsyth and Pollard’s images create a context for the shifting narrative. One moment, the musician is crafting a song at the piano, the next he sits behind the wheel of a car, while a range of his collaborators sit shotgun in the passenger’s seat.

Like Jarmusch’s film, 20,000 Days On Earth has a rapturous way with spoken language; carefully chosen words are the primary vehicles driving Cave’s narrative songwriting expressed in his statement, “It’s a world that I’m creating—a world filled with monsters and heroes.” Forsyth and Pollard’s lush camerawork—with the sharp eyes of cinematographer Erik Wilson—capture Cave immersed in his process as he composes songs on an old-school typewriter. His fingers bang at the keys, as we hear his voiceover on the soundtrack like the voice of a prophet with a taste for punk rock-inflected blues. In many ways, this documentary demonstrates that Cave has evolved into a complicated artist who is difficult to categorize even though his music is most frequently labeled as alternative rock.

At one point, Cave explains, “Songwriting is about counterpoint” and the juxtaposition of disparate ideas that collide, “then you wait and wait.”

But how do you visualize songwriting, which is essentially an internalized process? Forsyth and Pollard’s answer is to craft a movie that plays with the documentary aesthetic almost as if the form itself is a song struggling to find its ultimate shape. With their background in directing music-videos and installation art, Forsyth and Pollard rise to the occasion, mixing cinema verite footage of Cave writing and recording songs for his album Push the Sky Away with more polished, structured scenes obviously set up for the camera. For instance, the film includes a series of talks where Cave discloses childhood memories and his relationship with his father to a real psychologist. During these filmed sessions, the shrink nods and listens attentively. But these scenes are lit as if Cave is a character in a film noir.

Eventually, the psychologist poses the question “What do you fear?” Cave pauses for a moment. Then, his response cuts to the chase: “My biggest fear is losing my memory because memory is what we are.” This simple statement beats at the heart of what makes 20,000 Days On Earth such a fascinating mash-up of artist memoir and performance as the singer is enthralled by the promise of songs that will hopefully break through to a shared epiphany and transcendence for musicians and audiences alike. This cinematic soul train of Cave’s reminiscences and visits with his old friends is a kind of metaphoric walk down memory lane.

Despite the film’s slick veneer, Cave raises the issues that have defined his life and art with a candor that draws you into this beguiling portrait of the artist as storyteller. It isn’t necessary to know Cave’s brilliant music beforehand, but it certainly helps. This is especially true since many of the faces on screen are not attributed until the film’s closing credits. This lack of attribution is a risky move for Forsyth, Pollard, and their editor Jonathan Amos, and it’s part of their strategy to keep Cave as the film’s focus, jettisoning the usual devices that we come to expect in documentaries about prominent artists and musicians. So it’s no surprise that 20,000 Days On Earth took home both the Directing and Editing Awards for Sundance’s World Cinema Documentary section.

During the post-screening Q&A session, the filmmakers remarked that they wanted their film to evoke a range of feelings in the audience. Pollard said, “For us, it’s the feeling that you get from knowing Nick.” When asked about Cave’s response to the film, Forsyth said, “Nick said he could see himself in the film.” Audiences at Sundance also got a tantalizing glimpse into the inner workings of this enigmatic singer whether they are hardcore fans of Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds’ combustible mix of punk-fuelled blues and angst or newbies who have never heard his music before watching this striking film.

Ironically, one of the most disturbing and memorable films at Sundance 2014 was writer-director Todd Rohal’s remarkable short Rat Pack Rat, which also places an eccentric singer at the heart of its twisted tale. This film’s low-budget atmosphere quickly immerses you in the characters’ isolated world of medical oddities with touches of surrealism and an air of dislocation that even David Lynch would envy. The 19-minute dark comedy about a Sammy Davis Jr. impersonator’s close encounter with a bed-ridden Rat Pack fan with more than his share of serious health and emotional issues left this viewer perched on the edge of his seat with its genuinely shocking twists.

However, Rat Pack Rat never loses touch with the characters’ broken humanity. The fact that the film puts you in the main character’s shoes as he faces a major decision at the film’s jarring conclusion is no small feat. Rohal’s storytelling chops drive home his points without mercy. Keep a lookout for this brilliant short film with teeth that won Sundance’s Short Film Special Jury Award for Unique Vision. No kidding.

Films like Only Lovers Left Alive, 20,000 Days On Earth and the razor-sharp gem of pure weirdness that is Rat Pack Rat, among others, prove that Sundance can still deliver the goods for festivalgoers craving new experiences. During a post-screening Q&A session, one audience member’s question for the creator of Rat Pack Rat was simply “What the fuck?” As the audience waited for his response, Rohal gripped the microphone and calmly says “Thank you.” It was a perfect Sundance moment.

Regions: Utah