‘American History X’: An Independent “Classic” Turns 25

A quarter of a century later, Tony Kaye’s film feels naive at best.

In a recent career retrospective for GQ, Director Martin Scorsese said, “Every other person is like Travis Bickle now.”

This brief blurb is in reference to Scorsese’s 1976 Palme d’Or-winning film “Taxi Driver,” which explores the alienation and racial bigotry that causes a twenty-something year old white man — the name-dropped Travis Bickle — to commit abhorrent violence. Scorsese’s quote speaks to the unfortunate relevance the film still has four decades later, in an era where white supremacist and far-right mass shootings are all too common.

Twenty-two years after Scorsese made “Taxi Driver,” British commercial director Tony Kaye sought to explore similar themes in a more explicit manner with his feature film debut, “American History X.” Despite the troubles that plagued the post-production process (it was taken away from Kaye and edited without his input), the film opened to rave reviews, with praise given to the performances and the film’s searing portrayal of racial hatred, and even scored a Best Actor Oscar nomination for Edward Norton. But a quarter of a century later, “American History X” feels, at best, outdated and naive.

“American History X” chronicles the lives of the Vinyard family, namely brothers Derek (Edward Norton) and Danny (Edward Furlong) and their relationship with white supremacy. The film’s inciting incident begins with Danny getting in trouble for writing a civil rights paper about Mein Kampf, upsetting his Jewish teacher Murray (Elliot Gould). Danny’s Black principal Sweeney (Avery Brooks) threatens to expel him unless Danny takes a one-on-one current events course taught by Sweeney himself. Sweeney’s first assignment for Danny is to write a paper about Derek, a former neo-Nazi gang leader who’s being released from prison the same day.

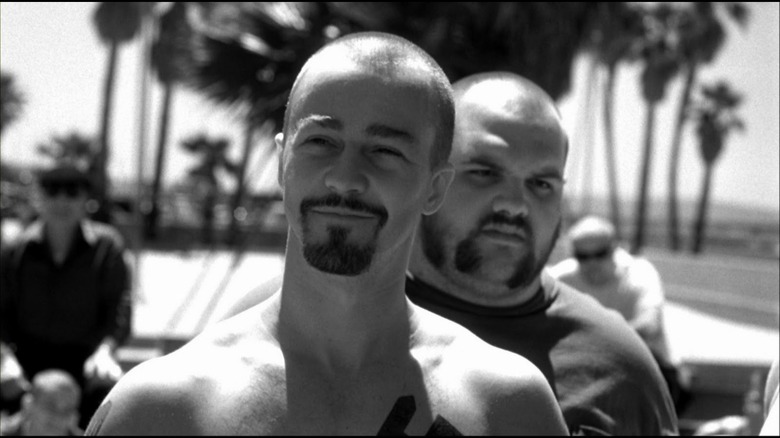

From here, the film takes a nonlinear approach to its story, with Kaye shooting present day scenes in color and flashbacks to the recent past in black-and-white. We see a variety of Derek’s increasingly radical views on race, everything from dinner table rants about Rodney King to brutally assaulting a Korean-owned grocery store that employs immigrants. This culminates in the film’s most infamous scene in which, after a group of Black men attempt to steal his car, Derek curb-stomps one of them to death. Afterwards, Derek is jailed for manslaughter. He initially joins up with the Aryan Brotherhood, but leaves after realizing that the gang does business with non-white gangs. Derek is subsequently attacked and raped by the Brotherhood in the showers. Throughout all of this, Derek slowly becomes friends with a Black inmate named Lamont, with whom he works with in the laundry room.

In the present, Derek, having given up his racist beliefs, is released from prison and returns home to find Danny falling down the same path he did, and does his best to steer his younger brother away. Although Derek seems to get through to Danny, it’s all for nothing, as Danny is confronted in the bathroom by a Black student he’d quarreled with earlier in the film. Danny is shot and dies in Derek’s arms.

Despite its intentions, “American History X” fails to correctly diagnose the real cause of white supremacy and ends up resorting to cliché motivations that feel like excuses for the characters. The main catalyst for Derek’s racism is his father Dennis (William Russ), who’s shown in a flashback to have held racist beliefs himself. This on its own might have worked, showing how casual racism can be passed down and morphed into more extreme prejudice. But instead, the film reveals that Dennis, a firefighter, was shot to death by Black drug dealers while putting out a fire in their home. It’s an incredibly contrived way to provide a “justification” for Derek’s hatred.

The other issue the film has is that it’s too fascinated and enamored with the time Derek spends as a neo-Nazi leader. The film gives Derek multiple monologues, where he gets to spew racial slurs and hateful rhetoric with little to no pushback. In one scene, Derek challenges a Black gang to a basketball game to decide who gets control over the Venice Beach courts. The game is shot with a mixture of wide, sweeping shots of the court, energetic handheld work, and stylish slow motion. It’s edited with quick, propulsive cuts, all of which accentuate Derek’s movement and his skill as a player. The entire sequence is scored by loud, bombastic trumpets and horns, with a triumphant melody that would feel at home in any inspiring sports drama.

On some level, what Kaye is doing here is intentional, using cinematic language to show what makes Derek a charismatic and effective leader. But the film fails to rebuke Derek’s ideology or even reconcile with his actions. The reason motivating Derek’s fall into extremism feels utterly melodramatic, and the film does nothing to explore the psychology behind fascism. It also feels incredibly tone-deaf to ask the audience to be sympathetic for a man who, regardless of any changes in his beliefs, brutally murdered three young Black men.

“American History X” has an admirable goal, and the film should be commended for tackling heavy political issues head-on. But in a modern context, it simply doesn’t hold up to scrutiny. Its examination of white supremacy is surface-level and the film doesn’t seem to have a real grasp on what drives someone down such a path. As Martin Scorsese observed, every other person might be Travis Bickle now, but no one is, or ever really was, Derek Vineyard.