Otosan – Lonely Lord: Hikikomori, Posthumanism and the Early Works of Aphex Twin

Hikikomori: a middle-class Japanese youth withdrawn from social conventions; engages in all social interaction via computers.

The 1990s and early 2000s introduced digital communication, a phenomenon purported by East Asia, leading to a shift in the otherwise harmonious marriage between language without sound and sound without words. With this newfound method of communication, a new question emerged: does technology strengthen or hinder visibility for previously esoteric forms of language? Historically, academic disciplines have been largely concerned with the speaking being, as languages in the Indo-European category evolved to place higher emphasis on real-time speech as to situate the body of a speaker in direct communication with their subject.

Historically, Indo-European applications of linguistics emphasize speech, while languages such as Japanese, that originated in written form, can better alienate a subject from its speaker. British cultural critic Scott Wilson makes this connection between the Hikikomori movement and the social bond in Japanese cultural practices: “The subject of desire,” he wrote, in his 2010 article “Braindance of the Hikomori” published in critical theory journal Paragraph, “‘is an element among others of a ceremonial where the subject composes itself precisely.’” In “Braindance,” Wilson positions individual subjectivity in a Western context, different from the artistic formality of Eastern social ritualism. This comparison purports an idea that the Japanese social experience was perceived as more decisive by the West.

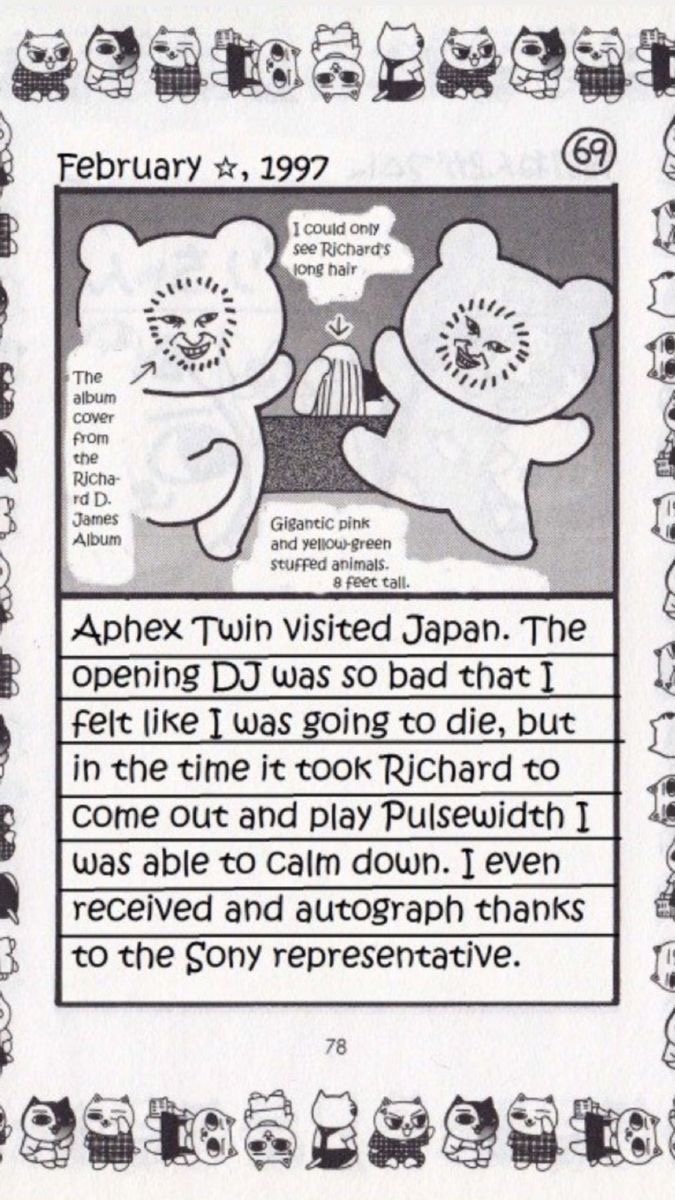

Although hikikomorism originated as a paranoid fantasy, this newly discovered overlap constructed an omniscient eyewitness account and simultaneous figurehead of those who interact exclusively through virtual means. In the late ’90s came the realization of the “Bedroom DJ,” an international figure of post-human sociocultural practices. Originating from game theory, the socioeconomic prospect of efficiency within communication practices was an important factor in the socialization of individuals who partook in hikikomori in quick and close correspondence to the proto-futuristic and ambient tone of British musician Richard D. James, better known as Aphex Twin.

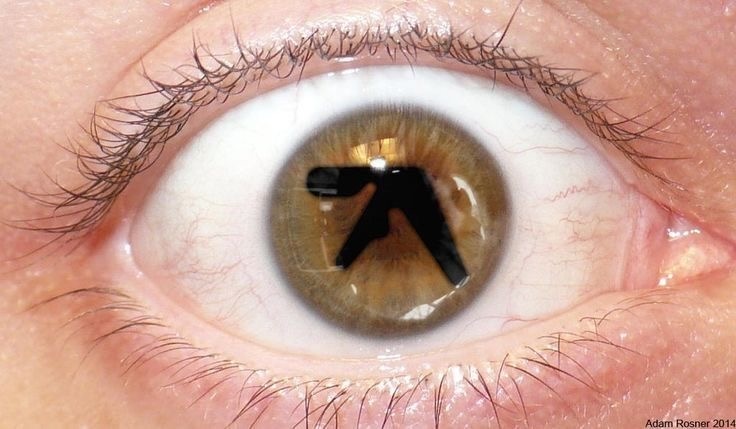

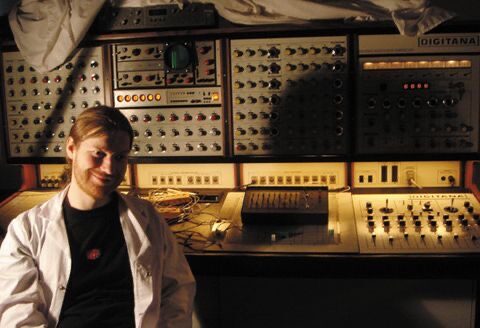

Emerging in the late 1980s, James garnered notability as a DJ in various clubs throughout South London, known for pioneering the genre of “intelligent techno,” inspired by cerebral tracks. James’ first critically acclaimed work, Selected Ambient Works Volume II, was produced in his home studio, a bedroom in his parents’ basement. Selected Ambient Works was a double CD produced in a space of perpetual fatigue. “This was me basically going asleep, dreaming up a track in an imaginary studio with imaginary equipment, and then waking myself up and re-creating that track,” recalled James, noting the speculative nature of his works. It is a speculation that becomes reflexive with repetition. The individual tracks on the album did not have names or titles, but rather tracks were denoted by thumbnail images of either the alphabet or hieroglyph. This wasn’t new for James; preceding works of his, like “Windowlicker,” also carried perverse modes of ambiguity, both aesthetically and sonographically. The use of delay and tone create a reflective yet distorted atmosphere for the listener — with James coining the term “braindance” for description and developing a centerpoint of stimulation for the electronic genre.

By the 2000s, hikikomori spaces were in direct communication with the ambient work of Aphex Twin, the notion of braindance implying a point of introspection within the electronic genre that serves as an ambient backdrop to the audio-visual dependence of hikikomorism. A stance dependent on non-physical environments introduces the idea of the hyperobject, a term conceived by ecophilosopher Timothy Morton to describe entities so large inscale they outsize human perception entirely. One invention within the definition of the hyperobject is the Internet. Morton’s concept of hyperobjects has been widely adopted by the social sciences, citing the Internet as the supreme representation of the hyperobject in the 21st century. Hyperobjects adhere to the entities that engage with them, this case being the hikikomori, and are willing to change in form or function to accommodate their users.

The feeling of insanity that can arise when listening to early works of Aphex Twin acknowledges a period of rhythmic synergy. Critics acknowledged Aphex Twin’s commitment to a rhythmic ambiguity that coincides with traditional electronic music but deviates through an asymmetry between modes of sound and language. The works produced by James between 1995 and 2001 were characterized by rapid and asymmetrical rhythmic sequences referred to in formal analysis as MicroRhymatic Ensembles. In 2015, Musicologist Anthony Papavassiliou, a researcher at Laval University, studied breaks in Aphex Twin’s “Windowlicker” which force a listener to continuously re-evaluate the structure of the rhythm, forming an open-ended approach toward aesthetic sonification and acknowledging a mode of sound within a piece. This emphasis on habitual asymmetry consistent within Aphex Twin’s work directly paralleled posthuman generativities and sentiments. Braindance was a genre that drifted and imagined a use of sound that was never fully alert, representing the essence of self-reflexive and socially autonomous individuals who characterized the social guidelines of the hikikomori.

This subversion of commercial electronic music was imitated in James 1997 “Come to Daddy” music video, which features images of children (all with the face of Richard D. James) engaging in various erratic adversities before coming face-face with Dad, a skeletal figure with the face of Nosferatu. The visual and musical clichés addressed by critics mainly suggest that the vulgarity of posthuman irony comes from a position of inertia and lack of synaptic correlation with the physical world. This manifestation of internet art — the medium of code and aesthetic sonification — fostered intercreativity. James himself was accused of solipsist sentiment, the tones of his music not definitively concerning a physical environment. Consequently, language becomes somewhat displaced in “Come to Daddy” with the introduction of internet art, its many genres filling the gaps between material and proto-geographical origin.

“There’s something magical about having all your equipment in the same room as your bed, and you just get out of bed and like, do a track in your pants and stuff.” The work of Aphex Twin centers James’ physical and speculative proximity to the digital sphere. A listener immediately immerses in its complexity and from that, its beauty. The crux of the hikikomori is the tension between solace and disturbance, which is embodied in James’ early work. Ambient Works II is an album that lives in a bubble, made for the self-amusing and introspective essence of a posthuman atmosphere.