Directing Under Dictators: Shin Sang-ok, the Prince of Korean Cinema

In 1978, the South Korean Park Chung-hee regime shut down a film studio that defined the country’s postwar film industry after the release of a forbidden kiss scene. Six months later, the studio’s head was abducted by the North Korean Kim Jong Il regime. The head was a South-Korean director and producer, Shin Sang-ok, who directed the film that caused the controversy: “Rose and Wild Dog.” Shin’s career survived two authoritarian governments, as well as an abduction and imprisonment. Through these constricting experiences, he continued to make films — whether under surveillance, direct orders or freely, proving that systems of censorship and political warfare will fail in their efforts to squash creativity and passion.

After starting his career in the freshly post-war South-Korean film industry, Shin quickly grew to fame with his popular melodramas. His company, Shin Films, became one of the country’s most influential studios, producing over 300 titles during what is considered to be the “golden age” of South-Korean cinema. This earned the director the nickname “The Prince of Korean Cinema.” Yet, from the beginning, his artistic freedom and creative independence was restricted by censorship.

In 1962, the Park regime seized control of South Korea after Park’s 1961 military coup. Shin’s creative liberties were cut short soon thereafter. The new regime sought to gain ideological control over the industry and make film a propaganda tool for Park. With the 1962 passing of the Motion Picture Law, the Ministry of Public Information controlled the South-Korean film industry through the producer registration system, regulating film import, and enforcing censorship guidelines with mandatory screenings before distribution and licensing. Politics, social issues and ethics in films were subjected to significant censorship and oftentimes punishment towards the responsible production studio — unless the film could be used as pro-South Korean propaganda, in which case the production studio would be rewarded by the Park regime. These strict guidelines limited the ideological and creative autonomy for filmmakers, prompting a rise in formulaic genre films.

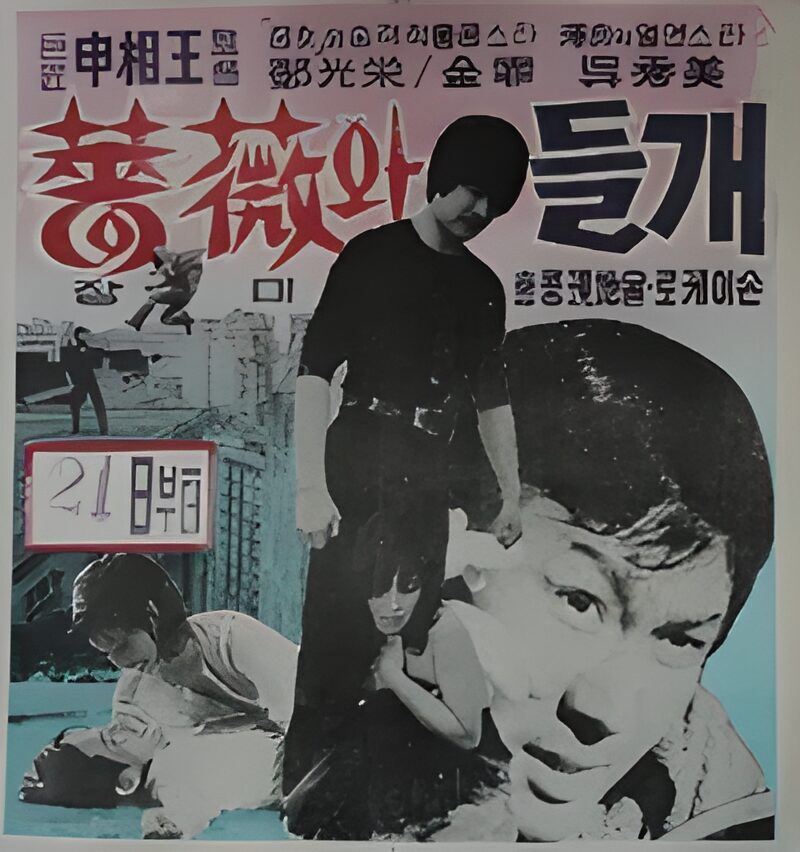

At first, Shin obliged by Park’s requirements and Shin Films was favored by the regime for its quality, yet ideologically safe, films. But in the early 1970s, Shin began experimenting with increasingly independent artistic choices that did not adhere to the regulations. Shin Films’ dominance in the industry and Shin’s willingness to challenge government norms became a liability for Park’s agenda for South-Korean cinema; In 1975, Shin and Park’s censorship battle climaxed with the teaser release of Shin Films’ “Rose and Wild Dog,” a film which would prove to be on the cutting edge of South-Korean censorship policy.

“Rose and Wild Dog” (1976) featured a kissing scene with partial nudity — an act against Park’s obscenity regulations. Shortly thereafter, the South Korean government revoked Shin’s filmmaking license and halted Shin Films from producing further films. The studio officially shut down in 1978.

“Those three years [1975–78] when I was forcibly kept away from film represented the most difficult, frustrating and unbearable period of my life,” Shin said in his 2007 autobiography, “I Was a Film.”

Shin was forbidden from legally producing a film in South Korea. Additionally, his former wife and South-Korean actress, Choi Eun-hee was missing and later claimed to be taken by North-Korean agents. Seven months later, Shin traveled to Hong Kong to find his missing lover and star of many of his films, and went missing.

The alleged kidnappings of the South-Korean cinema icons remain controversial to this day. While some believe Shin and Choi fled to North Korea to escape the Park’s stifling censorship, Shin and Choi recount Kim Jong Il ordering North-Korean agents to kidnap them and forcibly make propaganda films. From the moment Choi and Shin went missing until their arrival at the U.S. embassy, varying interpretations of events told by the parties involved lend to conflicting principles of what actually transpired.

Kim Jong Il, a publicly pronounced cinephile, desired to strengthen and internationalize the North-Korean film industry, and sought after one of his favorite directors of the time, Shin, to accomplish his ambitions. Just as Park desired to use film as a political weapon, Kim sought to do the same. After Shin was imprisoned for refusing to oblige to the Kim regime’s demands, the couple was reunited in 1983. Kim established Shin Film Productions as a North Korean production company, restoring Shin’s license to create films.

“Thinking I had nothing to lose, I said I wanted to explode a real train to enhance the movie’s special effects,” Shin said in his autobiography “I Was a Film.” “In response, the approval came immediately. This is only possible in North Korea. It’s the first time I experienced a film shoot so spectacular.” Shin’s appreciation for the North-Korean government’s resources speaks to the urge to produce a cinematic masterpiece. “I Was A Film” captures the nuanced experiences of Shin under Kim’s censorship, sparking controversy over Shin’s willingness to make North-Korean propaganda films.

Although certain liberties were given to Shin, he was still subjected to strict ideological censorship. Kim personally oversaw Shin’s productions, acting as an even stricter governing body than Park’s Ministry of Public Information. Each film was chosen specifically for its ability to act as a propaganda film to promote North Korea in a positive light after the Korean War.

“Pulgasari” (1985–1986) — Shin’s last film made under the Kim regime — is a kaiju film made per the wishes of Kim Jong Il, as he desired to profit off of Japan’s success with “Godzilla” (1954). Kim believed producing a kaiju, or “strange beast,” film like “Godzilla” would appeal to international audiences and open doors for the North-Korean film industry to establish itself alongside Hollywood. Shin viewed “Pulgasari” as a bifold opportunity: both to critique the North-Korean government, and for himself and his now remarried wife to escape to the United States.

Often watched for its hidden political allegory — an allegory which is hinted to be present, but was never confirmed — “Pulgasari” found a unique modern audience. Many audiences suspect the titular character Pulgasari, an iron-eating monster who helps villagers overtake their military government, only for the villagers to have to kill him to save their iron cooking and farming equipment, is representative of the nuclear bomb. With Kim attached as executive producer, Shin resorted to political allegory as his only viable way to express dissent in a subtle manner that could evade censorship.

Before “Pulgasari” was shown to the North-Korean masses, Shin convinced Kim to allow him and Choi on a business trip to Vienna under the guise that they were making deals for the international distribution of the film. Shin allegedly paid off a cab driver to drive them to the U.S. embassy, where they sought and were granted asylum. During their asylum process, Choi gave the first known recording of Kim Jong Il’s voice to the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency, which allegedly included Kim demanding the couple to make films for him.

Shin moved back to South Korea with Choi after post-abolition reforms in the 1990s, and released his 1994 film, “Vanished,” which critiques military dictatorship in South Korea and North Korea, as well as the U.S. government’s involvement in international affairs. “Vanished” was well acclaimed in the international independent film realm, and even had a special screening at the 1994 Cannes Film Festival. It was Shin’s last major film before his 2006 death.

Shin Sang-ok may not be universally known, but his legacy portrays the paradox of censorship — it suppresses, but can also sharpen subtext and symbolism. Shin embodies survival and adaptation under different forms of censorship.

Cinema, in times of censorship, is not only a tool of control in the hands of the government, but can be an act of resistance in the hands of people like Shin.

Regions: Boston