Filmmakers and Their Global Lens: Eugene Jarecki

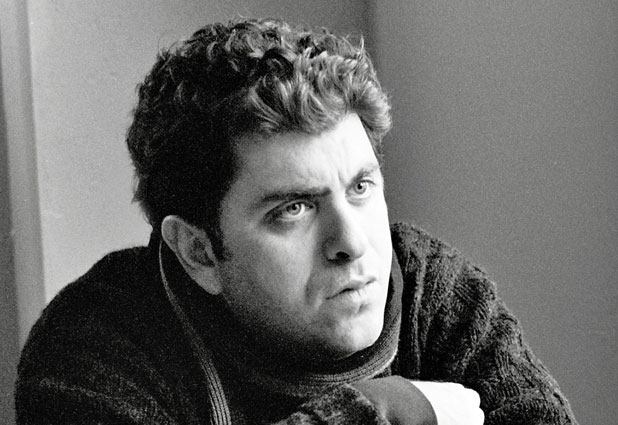

In this installment staff writer Dana Knight speaks with the documentarian behind Why We Fight and The House I Live In.

The Independent’s Dana Knight met Eugene Jarecki at The International Festival of New Latin American Cinema in Havana, Cuba in December 2014.

Dana Knight: When did you start making films?

Eugene Jarecki: I started making films when I was about 21 years old and I was getting out of college. I had been a stage director of plays, I was inclined toward plays and theatre about the human condition, humanism, political conditions, political revolutions, the need for political systems that are of service to humanity, that was even a theme in the plays that I did, sometimes Shakespeare, sometime other [authors]. But when I got out of university, the idea of reflecting some of those passions in movie-making captured me, probably not for very original reasons. America was seeing the birth of what has now become the quite famous “independent film movement” and I was graduating college in 1991 right when that was happening.

DK: Did you go to film school by the way?

Jarecki: No, at that time it was just university. I decided to start studying film on the side at New York University. I took some film classes, mostly just as a technician, to learn about lenses, editing, lighting, composition. The direction of actors and the direction of scenarios, that had come very naturally with the training and experience I had with stage plays and bringing that into the world of movies was exciting for a lot of reasons. And yet I had probably envisioned that I would be a Hollywood filmmaker, it wasn’t clear to me that I would make documentaries. Documentaries at that time were things you saw in school in a boring lunchtime in your cafeteria with a projector burning the film and showing it on the wall. And sometimes they were good and sometimes they were bad, they always got you out of class and they gave you an opportunity to sleep without being noticed by the teacher! So that wasn’t really what I thought I would make my life about. I thought I would make my life about more obvious Hollywood or independent films with actors. And to this day I still do that kind of work also but my documentary work is what I’ve become more known for.

DK: Could you talk about making your first documentary and the subject you chose to explore?

DK: Could you talk about making your first documentary and the subject you chose to explore?

Jarecki: In my early 20s I was working on scripts for Hollywood films and I had plans to make Hollywood films but that was very difficult to make happen. It’s very competitive and it’s actually very hard to write a very good screenplay, you see so few movies that are really good. And I wasn’t content to make something bad, so it was a struggle almost within myself to find a voice that I found credible and passionate. While that struggle was going on, I had to make a living, so I started taking whatever jobs I could using a camera or being of service on movie sets. But I also did some political work at that time, I worked for a couple of politicians, very often in sort of media-thinking and media strategy and by accident I ended up on a state department delegation from America to come to Guantanamo Bay. It’s funny that I’m here in Cuba now…

DK: So that’s your connection to Cuba?

Jarecki: In a way, although I never left Guantanamo Bay at that time. I just went there and I filmed a crisis that was happening with patients who had been detained at sea and were suspected by the US government of being HIV-positive. And they had been brought to Guantanamo and kept there in conditions that they were protesting with a hunger strike. So I had been sent with a bunch of members of the US state department. And Jesse Jackson was going to go down and mediate the hunger strike. Instead, as it turned out, he joined the hunger strike because he found the conditions unacceptable. And that was a very dramatic thing to film and I suddenly found myself there […]. I had gone down with cameras because it sounded like an exciting piece of history and I brought cameras with me. And those cameras captured the images of that day. And when I got back to New York I was contacted by the news media because strangely it turned out I was the first person to have filmed inside the base. And I was only allowed to film because no one questions the presence of cameras since we were with the state department. So I got back and I had this strange independent status in the middle of this otherwise official delegation. And that created an opportunity and I sold these images to television. And I never sold anything in my life, I could barely get arrested in Hollywood! So it was a very exciting shift for me when suddenly I realised that I could film real images from the real world and make things that people wanted to see. And from that day forward I started quite passionately finding ways to express myself, my concerns about the world, my desire to see systems improved, my feelings for human beings and their struggles through documentary film.

DK: From all the documentary films you made so far, which one is the closest to your heart?

Jarecki: That’s a different question maybe from which one I think is the best film. I think I’m best known for the film Why We Fight or maybe for the more recent film The House I Live In. Both of those are kind of larger profile than the other films. The House I Live In is probably closest to my heart because it concerns people very close to me and communities with whom I’ve been captivated for most of my life.

DK: The subject of your film, the drug war, is so universal, it’s happening in so many places but you weaved in a very personal narrative, you had a very personal introduction to the film and ended on a very personal note, which made it very moving.

Jarecki: Right, that was the goal. The film is both a kind of universal look at a subject, a scientific look, a political look, an economic look. It has all those elements but I wouldn’t have been interested in the subject in the same way if I didn’t have such a personal connection to it. And I have a personal connection to the drug war in a different way than a typical poor person in America because the drug war targets poor people, it doesn’t target comfortable people like me. So my connection to it is second-hand, it’s through the experience of others with whom I’m connected that I actually saw the difference between their life experience and my own. And that difference in a way is the main subject of the film. Even though the film is spending most of its screen time on the special damage that the drug war does to communities of colour, the poor communities in America. What shines out so terrifyingly is how history has repeated so often and abuse by the strong of the less strong, of the advanced of the less advanced, of the defended against the less defended. You see this chapter by chapter throughout history and the American drug war is just the American version and the latest version.

DK: This almost makes democracy and all the big words we have, the American dream etc, a joke. There is a point in the movie when someone says, “The real question we should ask is not: why the addiction? It is: why the pain?” So why are the American people suffering? They are the consumers of drugs after all.

Jarecki: That’s a beautiful question. The American people are suffering, yes. And they are suffering from a kind of heartbreak that came with the collapse of the American dream. And the American dream collapsed because capitalism in many ways almost came to destroy democracy in America. And the American dream is made of that idea of democracy and when you unleash capitalism against it, [it weakens it]…Democracy is a more noble system, it’s probably a more sustainable system, a more survivable system and of course a more decent system. But it doesn’t have the “weaponry” in the short-term to fight back against capitalism which has very powerful short-term weaponry, very powerful short-term incentives that cloud people’s judgement, divorce them from better sense. So at the end of the day, capitalism is winning this contest right now. Of course, in the long run, in human history, democracy has made great strides and I don’t know if the current American chapter of abuse is going to end that long historical story. Unless America and the other partners in the Western world allow that kind of capitalism in the modern era to continue unchecked. [If that happens] the planet won’t survive and if the planet won’t survive, nor will the democracy on it.

DK: Your film is not only about the drug war, the topic is so much larger than that because this problem permeates so many other areas of life.

Jarecki: Yes, there was no way to pursue the investigation of this film without following it into areas that stretch very far and wide.

DK: One compelling argument you make in the film is that the drug war is also race-related. You say that the war on drugs is never about drugs, it’s always connected with race. And you go back in history and give the example of the Chinese immigrants in America and the need for them to be eliminated from society for economic reasons. Can you expand on that?

Jarecki: America’s history is so much a history about race, America has struggled with racist issues ever since the country started. And that makes a lot of sense because America also tried to be and was quite a multi-cultural ground and such a place is more likely to have racial concerns than a racially monolithic place. Very often we talk about the example in Nordic countries: look how great Norway is at this, look how great Sweden is at that. And Americans would rightfully say: look at those countries, they are all of the same cultural background, they have very similar common denominators. This country is trying to balance the complex interactions of an incredible tapestry of people. And as these Nordic countries now take on African populations, Asian populations, Middle Eastern populations and other non-Nordic populations, they too meet greater complexities, as we’ve seen in Holland and elsewhere. So I think that America’s history is specially about race but that’s not special to the American people or their psyche, I think it’s special to the American experience.

Having said that, there is no way therefore to take a look at American history with something like our drug laws. One would imagine that they have nothing to do with race. But what is surprising is that they have everything to do with race and actually nothing to do with drugs. As you may know, we’ve been at this for over 40 years, we spent over a trillion dollars, we had 45 million drug arrests and what do we have to show for it? Nothing. Drugs are cheaper, purer, more available than ever before and more in use by younger and younger people than ever before. The only thing we do have to show for it is the vastest prison population, 300 million people behind bars. And this proportion of the population is racially profiled. And this tells you that we have not only an explosive and disastrous approach to drug control but that within that, it has been incredibly influenced by those strands of racism that already surged through the country’s veins. So looking back, the first drug laws we see in America are the opium laws targeting the Chinese. It wasn’t illegal under the opium laws to take opium all across America, it was only illegal in California, where Chinese immigrants were landing. And it wasn’t illegal to use opium in any way, it was only illegal to smoke opium. White Americans used opium widely but they didn’t smoke it, that is a Chinese practice. So we were concerned with that time, we being the American public consensus. The government was concerned about the arrival of the Chinese migrant workers willing to work for cheap, willing to work longer hours, and therefore a threat to American job security. Well, if you’re the land of the free and the home of the brave, with all men being created equal, you can’t exactly just put people in jail because they are Chinese, you have to have a defensible-sounding rationale for putting them in jail. So you make something illegal that is a practice of theirs. It’s not just a coincidence that this happened to be a practice that just these people do. And this is true in the case of Mexican Americans targeted by our marijuana laws. Until the use of the word marijuana, that plant was just called hemp. We suddenly started calling it “marijuana” when we wanted to mexicanise it and identify it with the Mexican communities. We also call it “Mexican opium.” So at that time we’d look at that drug and identify it as a specially Mexican practice. And therefore we’d have reason to suspect that any Mexican person walking down the street is being involved in that practice more than this other person. We saw it happen to Black Americans with cocaine, first at the turn of the 20th century, then again in the latter part of the 20th century with the arrival of the crack cocaine. Crack cocaine has always been thought of as a Black drug, as if the majority of the crack users are Black. But the majority of the crack users have never been Black, they have always been a minority of the crack users. Black people represent 13% of the American population. Lo and behold, they are 13% of the crack users, meaning they use drugs no more and no less than anyone else in the population and they are a minority of the population. You don’t have to be a math genius to realise they are not the majority users of crack. The majority of crack users in America are White. Yet strangely for a white person to go to jail for crack use is extremely unusual. About 90% of those charged with crack offences in America are Black. In a system where they are only 13% of the users. So that ratio disproportion speaks to the incredible racism in our drug laws which, over and over, chapter by chapter, turned out to have been wars of racial and social control more than laws of narcotics control.

DK: You also look at the roots of the problem, what got those people there in the first place. You say something very moving: when someone is denied a meaningful life, they turn to drugs. It’s such a logical argument, yet this problem is rarely addressed in society in a systematic way.

Jarecki: Sure. We just had lunch here and I ate things that my system is addicted to. And you also ordered an addictive substance, this has extremely refined carbohydrate in it, the milled corn, it has the very quick sugar of this pineapple, and that will speak to your system in an addictive way. If you’re feeling sad today, that probably will make you feel better. We all use addictive substances, I just drank tea, which is an addictive substance. We all have ways of using addictive substances, very often to make us happier. When you are profoundly unhappy, your need for self-medication rises precipitously so it is not surprising that we most often find serious levels of drug addiction among communities that suffer greatly. That’s why the doctor asks in the film “why the pain”? Where is the pain coming from that is producing the epidemic levels of addiction that people in the US suffer from? And the answer is, America is in pain. If you are a democracy holding the torch of the world’s hopes one day, and the next day you wake up to discover that the country had been overtaken by money, wealth and capitalism, [that is painful to acknowledge]. The 400 richest people in America today have more money than the bottom 150 million people. And in this situation, you cannot have a democracy. If you don’t have a democracy and they taught you to believe in democracy in school, what are you supposed to believe in? So it’s no wonder that people feel broken-hearted. For that reason and many other reasons, just basic to life on earth and a shrinking planet, with the climate problem, with challenges everywhere you look, it’s very understandable that people suffer. And in America, our suffering, in a mass-media culture, in a highly industrialised culture, and in a culture that has allowed many social institutions to collapse and bow to the God of capitalism, most often we buy a product to fix our pain. We consume to fix our pain. America has a capitalistic solution to everything including our pain. That’s why we have an industrialised medical system, so it comes as no surprise that we have an industrialised self-medication system known as the drug crisis in America.

DK: Having dwelt on this issue for a long time, do you see a way out in the near future?

Jarecki: Yes. But I don’t think the way out is an easy one. I think that America needs to take a long, hard look in the mirror and recognise how profoundly we have slipped as a country from what we idealised the country to be. It’s like suddenly realising that you need therapy and America profoundly needs therapy. And it needs the therapy of realising its tendency towards certain addictions. And the primary addiction of the country is the kind of consumerist quick fixes that come with capitalism. It is the capitalism’s answer to what the church once did for people, or to what literature once did, or what community once did, or what agricultural collaboration once did, or collective barn-raising, or small-town medicine. All the things that bound people together and gave them a sense of meaning, those things are lacking in modern life and they are replaced by a substitute that is in no way a viable substitute. Capitalism does not have the social concern, it doesn’t have the compassion, and it doesn’t have the long-sighted wisdom because it is interested in short-term profit. It doesn’t have the long-sighted wisdom to care for social affairs and human life, so it is no surprise that it has not provided for the health of the world. It has accidentally benefited people in certain ways when capitalism’s excesses happen to spill over and maybe produce this quality of life that can be pointed to. But while you pointed those, you must turn a blind eye to myriad others that haven gotten profoundly worse.

DK: Ironically though, your Cuban friend who greeted you at the screening of your film has such an idealised and naive view of America. He was saying, “I really hope I set foot on American soil before I die, I love America, God bless America.” This provided an ironic context to your film which is highly critical of the American system. Obviously your duty as a documentary filmmaker is to be critical and look at the whole picture but people from a country like Cuba only see what is positive about the American system and there’s probably a rationale for that.

Jarecki: Yes, that’s true. The Cuban people I meet in the streets and all over this country, and I travelled a lot around Cuba, they have an amazing love of the American people, and I think they have an amazing love of the idea of America and the impression of this undiscovered country north of here. But they also recognise that they see the American government over successive decades as being almost an invading force, like an occupying force, occupying those people and occupying that promised land. And it’s amazing that after so many decades that they maintain that distinction. It’s a beautiful thing that they do, it’s compassionate, it’s poetic and of course at the end of the day it is idealistic but thank God for that, we need more idealism. We need more idealism that combines with pragmatism to say that the world can be better, should be better and will be better. And meeting someone like that Cuban friend today, he is very critical of what’s in the film, he agrees, but he can also separate that from his sense of the American people. Two things can be true. F. Scott Fitzgerald famously said that the mark of an advanced intellect is the capacity to hold two conflicting ideas in your mind at the same time. And that is something that really defines the intellect of the Cuban people that I meet. They are students of history and they have watched two things be true. They have watched their own country succeed against America in many ways, yet they are also aware of the shortcomings of their own country. Both things can be true. They find the American people and the national concept wonderful and they can see the government as a negative and occupying force. It’s a very sophisticated way of understanding life. The rest of us tend to look in more black and white ways.

DK: What political system would you like to see implemented in America?

Jarecki: I don’t know, the closest we probably ever came was several years ago, the emergence of the social democracies of Europe, which were democracies that had a regulated notion of capitalism and a regulated notion of free enterprise and it had not yet become “Reagan-ised” and “Thatcher-ised” where you simply release all the regulations and imagine that somehow magically the rich will remember to take care of all of us while they are cashing their winnings. This was a deadly illusion and it is very easy to realise it was the work of crooks who convinced us of the counter-intuitive idea that somehow by the rich getting richer, that old story of the poor getting poorer, will stop being true. As the rich get richer, the poor have always become poorer. That’s a cliche for a reason. Reagan decided to teach us that that cliche wasn’t true. The cliche is true, most cliches are true.

DK: Also, if the ultimate purpose of all people is happiness, there is again this cliche that being very rich doesn’t lead to happiness.

Jarecki: Yes. People here are cash poor, they make 20 dollars a month and I can feel that they are happier than I am.

DK: What’s next for you?

Jarecki: I have a couple of TV shows that I’m developing, shows that are based in real life, with social and political themes. I have a couple of Hollywood films. Some other projects on prison topics and on the drug war. And a love story. I also have a couple of documentaries, a film that just got into Sundance which I executive-produced called Terror, about the nature of FBI investigations of terrorists. So it continues. I’m also shepherding the work of younger filmmakers. This film that got into Sundance is the work of one of the members of my team, he’s the producer, I’m the executive producer. He had a couple of friends working as directors and I’m shepherding that project along with others. So my life has gotten very rich because I get to help other people make their films while also continuing to make more directly my own expressions.

Regions: Latin & South America