Directed by Women: How About Shot, Edited, & Produced by Too?

Filmmaker and activist Ariel Dougherty reminds us of the abundance of films by all-women crews in the 1970s and 80s.

Over the past year, ever since the May release of the ACLU’s 15 page letter to the EEOC, there has been tremendous public discussion, and countless articles (like this and that), about the lack of women directing major motion pictures.

In contrast, a wealth of movies directed by women have emerged from the independent community for decades. Some are in distribution, many are not.

Even those works in distribution by stalwart feminist distributors like Women Make Movies or New Day Films are largely unknown to the general public. Too few cinema studies programs fail to bring forth feminist films of the past for study by contemporary film students, so a growing gap exists among young filmmakers’ knowledge of works from the germinal period of the 1970s and 80s. Film festivals as well have been lax in addressing the cultural bias against women directors. All of these elements combine to support only the status quo.

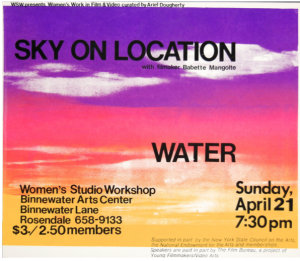

So I decided to skim through the long and wonderful list of Women Film Directors (6,634 were listed at the time of publication; it’s a work-in-progress and welcomes additions) that Barbara O’Leary has created. Babette Mangolte, #2439, popped right out at me. That’s because I included her stellar work, The Sky On Location (1982), in a series I curated called “Women’s Work in Film and Video” over an eight year period, starting in 1986. With support from the Film Bureau, then well-funded by the New York State Council on the Arts, this series often hosted filmmakers to speak with their works.

Women’s Studio Workshop, the sponsoring organization for this series, had wonderful graphic facilities. (They still do: www.wsworkshop.org.) Every show had a silk screened poster that circulated about the Mid-Hudson/Catskill region. (See more of the posters and other films that were programmed here.)

The April 21, 1986 bill featured The Sky On Location and the short film Water (1973) by Deborah Dickson (aka Water’s Dream). These two films are lyric scans of the natural world. The Sky On Location is about the relationship between vast land and sweeping sky of the American West based on a visual diary shot by Mangolte during roadtrips to the West in 1980-81. About it Stephen Price wrote, “Nowhere are [Magnolte’s] abilities as a cinematographer more evident.” In the short, Water, bubbling creeks flow down mountain slopes and effervesce as they crash against rocks and tumble further, hurling faster, then slower, as water meanders toward the sea. Both are about the natural landscape in motion, filmed by cinematographer directors.

On the Directed by Women list, the sole information posted next to Mangolte’s name is “Cinematographer, Jeanne Dielman, 23 Commerce Quay, 1080 Brussels.” This credit is monumental in itself.

The excellent, highly-skilled camerawoman framed and captured on celluloid one of the most remarkable feminist feature films of the period. Chantal Akerman’s now classic revolutionary film Jeanne Dielman, 23 Commerce Quay, 1080 Brussels (1975) follows a housewife through 72 hours within her own apartment – cooking, tending her son, and maintaining an income through prostitution. Akerman herself declared in a 2009 interview, “I made this film to give all these actions that are typically devalued a life on film.”

Shot with an 80 percent female crew, the film premiered at the Director’s Fortnight at Cannes. Despite many getting up, banging their seats and departing the theatre and Marguerite Duras shouting, “This woman is crazy,” the next day 50 festivals requested to screen the film. At age 25 Chantal Akerman had become an acclaimed international filmmaker. Eight years later, when Jeanne Dielman was finally released in the US, Vincent Canby wrote: “It’s about the looks and sounds of ordinary things and people, which it records with such precise, unsettling clarity that it has the effect of finding threats in mundane objects and doom in commonplace characters.”

Mangolte had a long working relationship with the Belgian filmmaker. She shot many of Akerman’s 1970s works – Hôtel Monterey (1972), La Chambre (1972), Hanging Out Yonkers (1973), and News From Home (1977) – and Akerman’s less well-known film on Pina Bausch, Un jour Pina m’a demandé…(1983).

But beyond Mangolte’s own works, which also include What Maisie Knew (1976), The Camera: Je or La Camera: 1 (1977), Four Pieces by Morris (1993) and Seven Easy Pieces (2007), Mangolte was the cinematographer on two distinctively germinal works by dancer-turned-filmmaker Yvonne Rainer: Lives of Performers (1972) and Film About a Woman Who… (1974). As B. Ruby Rich states in her book Chick Flicks (Duke University Press, 1998): “The effect of feminist thinking becomes even clearer in this [2nd] film….” Rich also quotes Rainer, “now she ‘could feel much more connected to my audience, and that gives me great comfort.’”

Rainer and Akerman were not the only renowned feminist filmmakers of the period to hire Mangolte. British director Sally Potter had Babette Mangolte shoot her first full-length dramatic feature, The Gold Diggers (1983). “Made with an all-woman crew, featuring stunning photography by Babette Mangolte and a score by Lindsay Cooper, it embraces a radical and experimental narrative structure,” states International House. Last year lucky Philadelphians had a chance to see The Gold Diggers and more significantly, the night before Mangolte held a conversation with the public.

In the British Film Institute’s DVD release of the film in 2009, critic Jonathan Rosenbaum lauds Mangolte’s cinematography. Rosenbaum was arguing against the initial unfriendly reception of Potter’s first feature:

“Just for starters, there are the gorgeous images by one of the world’s greatest cinematographers, Babette Mangolte — clearly her best work in black and white, as Mangolte has often maintained herself, and perhaps her most impressive work altogether. From the awesome opening pan across an epic Icelandic landscape, which suggests an etching or a woodcut almost as much as photography, the brilliance of Mangolte’s high-contrast palette and its surrealist impact…..defying the chestnut about black and white being more ‘realistic’ than colour, already makes this movie an extraordinary achievement.”

The dynamic between this particular woman cinematographer and three major feminist directors is profound. I am painting here only a modest image of the vastness of Magnolte’s impact on the visual terrain of feminist cinema. In the present day, while clamoring about the lack of women directors in Hollywood pictures, we can point to even fewer women working the key cinemagraphic element, the camera.

This came to mind when a friend mailed me the announcement for Women In Film and Video New England’s Flicks4Chicks contest. Why the lame guideline that only “AT LEAST one woman in a lead creative role: producer; writer; director; director of cinematography; editor” be a member of the team? Akerman achieved 80 percent on Jeanne Dielman and Sally Potter had 100 percent women crew for The Gold Diggers. In the days of making films and teaching filmmaking at Women Make Movies, 1969 through 1980, by my count of the 28 productions that had “A Women Make Movies Production” credit on them, we always had all-women crews.

It’s my opinion that if we knew the history of feminist film and did a better job circulating the works from the 1970s and 1980s, we could hold a grander vision and achieve greater equity in cinema – Hollywood and independent alike.