RIDM ’14: The Use and Abuse of Poetry in Documentary Film

Staff writer Patrick Pearce questions filmmakers about the "poetics" of film at Recontres Internationales de Documentaire de Montréal.

Gusts of bitingly cold wind eat away at the inch of precocious snow on the ground, offering a fittingly bracing backdrop to the Rencontre Internationales de Documentaire de Montréal (RIDM). Now in it’s 17th year, the festival offers a late-in-the-season “best-of” selection of international and Canadian films that favors essays, cross-genre films and other non-traditional documentary forms. With 71 occurrences of the word ‘poetic’ throughout the festival literature, staff writer Patrick Pearce invited three filmmakers from the festival to get together around a glass of wine to discuss their work and the idea of poetry in film.

To better follow the procedings, a few summaries and trailers are in order:

Nights, by Québec filmmaker and documentary history professor Diane Poitras, roams the streets and buildings of Montreal after dark, collecting snapshots, accounts and confessions of the city’s inhabitants and night shift  workers. Watch the trailer here

workers. Watch the trailer here

N – The Madness of Reason by Belgian filmmaker Peter Krüger might be described as an experimental biopic essay about 20th century French encyclopaedist, film exhibitor, musician and African adventurerer Raymond Borremans. With this character out to complete his encyclopeadic mission from beyond his tomb, this film draws a shrewd portrait of current day West Africa, it’s culture and spirituality. See the trailer here.

Dream Homes Property Consultants by Amsterdam-based filmmaker Alexandra Handal, is presented as a website for a high-end real-estate agency selling premium Arab properties to the Isreali market. Upon further perusal, viewers discover the homes are in fact Palestinian houses in West Jerusalem that were expropriated in 1948. Through the stories of displaced Palestians, this web documentary-in-disguise shares moving stories of uprooting and loss. Short films can be viewed on the site, and a trailer can also be found here.

Patrick Pearce: “Poetic abuse.” By this, I mean words like ‘poetic’, “poetry’, “lyrical’, ‘dreamlike’, etc. used abusedly in the context of documentary films.

Diane Poitras: I never use the word ‘poetic’ for my film, because often when people say, “I want to make poetry,” it’s a way of saying that if you don’t like it, it’s because you don’t understand my poetry. Sometimes it’s an excuse for not being rigorous, and my answer to that is poetry should be very rigorous.

Peter Krüger: I completely agree about the problem with the word ‘poetic’. It’s the same problem with the term ‘beautiful’. So we wouldn’t read any more that a film is ‘beautiful’, but it’s the same issue actually. If somebody says, “Your film is very beautifully shot,” then I think, “Oh, I have a problem,” because I have never wanted to make beautiful shots. The shots have a meaning and it’s not about beauty. It’s the same thing with poetic. In this words, there is no structure, no tension. If it’s abusive, that I don’t know but it’s maybe it comes out of an inability to defining the film in another way. You have to label it somehow.

PP: It’s kind of a short cut.

Alexandra Handal: Well I find it very unfortunate that words like poetry, at least the context of documentary, are used so loosely, because they lose their meaning. When you think of documentary, words such as truth and facts and history come to mind. And when you think of poetry, it’s the things we can’t explain, the things that we cannot put our hands on, and that’s very exciting to speak about that with documentary, because documentary wants to be something that’s certain but it’s not.

PP: “Gathering and classifying”

Poitras: I had a few pillars on which I could stand on but between that, I was just gathering. For instance, there is a street in Montreal that I know very well because I lived there for 10 years and I knew there were a lot of things happening in that street at night. It’s a little street, not commercial. And every night, at different times of the night, I would say, “Let’s go back to that street,” and people would say, “Oh no, not again.” The director of photography would be against it “because there’s nothing”. I would say, “Wait, there’s actually a lot of things going on.” This is where we got these women who are smoking, the man who’s doing his laundry, and the dog. And these were the type of things that I wanted to catch in the film. Actually, when I talk about my film, I say it’s a journey, exploring different landscapes and states, nocturnal states. This is what I was trying to do; gather the material what would help me to create that afterwards.

PP: And in your case, Alexandra, you were gathering, I felt, a kind of evidence, perhaps archival evidence.

Handal: Yes. It’s a bit like picking up remnants and it’s like an archaeological site. I was piecing together, so that’s why the narration took on many different forms. For example, when I say the directions of how to get to a home, I use landmarks. Palestinians, when they’re describing how to get from one place to another, often describe the place by describing who the neighbour is or what shop is next.

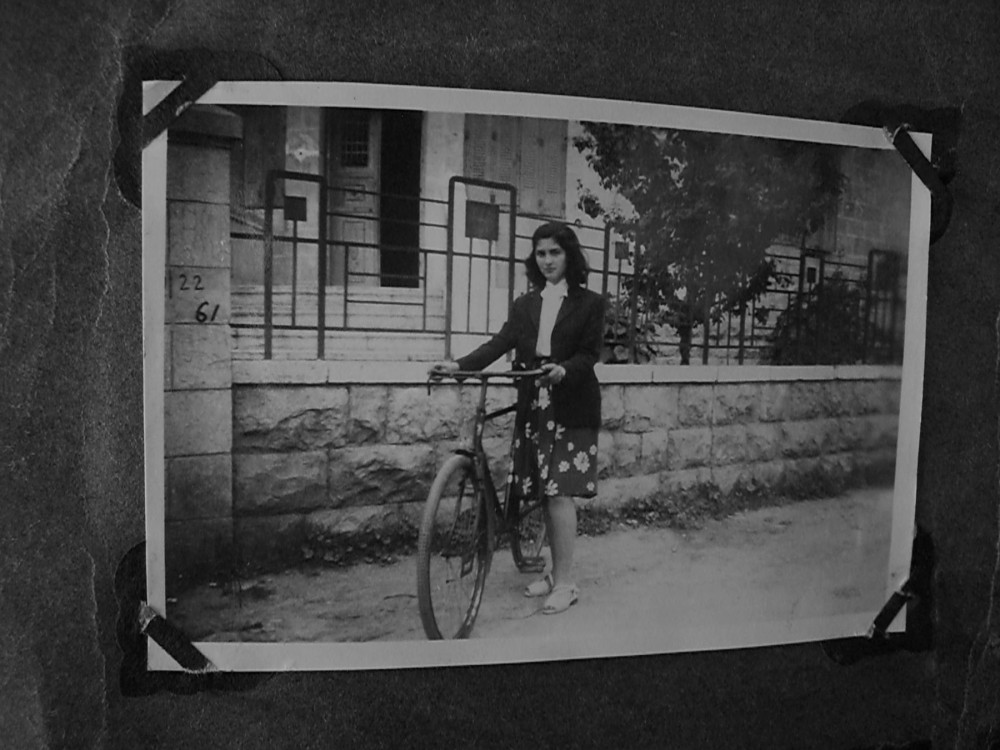

PP: The street where a girl often rides her bicycle, for example…

Handal: Yes. So you read the directions of how to get to a home in the present, it’s only later when you view the films that you actually realize that everything you’ve read – all the people, places – basically none of that exists anymore. These people are now refugees and are unable to get to their home. So ‘archive’ is not about that place far away in history; it’s the present. Memory is always about being in many states at the same time. It’s how you understand your present.

PP: By taking elements of the past and recontextualizing them in the present, you’re giving them, of course, irony…

Handal: Yes, exactly. That’s what I wanted.

PP: Peter, your film is all about classification, but I’m particularly interested in the classification of what is currently going on in West Africa and the conflicts, because your film, despite its fictional qualities, does have a traditional documentary grounding.

PP: Peter, your film is all about classification, but I’m particularly interested in the classification of what is currently going on in West Africa and the conflicts, because your film, despite its fictional qualities, does have a traditional documentary grounding.

Krüger: Yeah, absolutely. One of the reasons why I wanted to make the film has to do with the fact that classification is innocent when it’s just for an encyclopedia. But when you start defining people, i.e.: this person comes from Mali and that person comes from Burkina Faso, it’s the same process of classification. We give them a name; we give them a location; we give them identity cards. It’s also an act of violence in a certain way. In the Ivory Coast, this process of identification led to civil war. Similar to what happened with Jews in the Second World War; it’s something which comes back once in a while in history.

At one point our main character doesn’t know if he really exists or not, is he dreaming or not dreaming. Then in the middle of the film, he realizes that he’s dead. There’s no question about it. He has seen his grave. He died and now he’s a spirit in the world of the living… he doesn’t know why yet and at a certain moment, he has to find a new destiny.

In his perspective he thinks, “Well, I have to continue my work because it’s not finished. So I have to continue to define the world.” And the world he sees today, it’s another world. It’s a world with UN, with rebels and so forth. So I decided, if this spirit has a life beyond that, then it has to continue to define things he has never seen before. So he defines he sees rebels and he says, “R, Rebel” He discovers the UN and he says, “Ah, U-N”. But, of course, these are elements which are not in his encyclopedia, because he never experienced them in his lifetime, but which will be contained in future versions because an encyclopedia goes on and on forever. So this spirit will never have any rest because it has to continue to define.

PP: “Puzzle-solving”

Krüger: We had a very clear structure in terms of story. However, I also shot a lot in a very intuitive way. For instance, going to a cut and then other scenes starting, coming from black, going somewhere else. Panning up to the sky, and the next scene starting from the sky panning down, which means in the editing I had a lot of possibilities in going from one scene to another scene but in a very associative way. Of course, it gives an enormous liberty in the editing. It also means that you can create meanings you didn’t expect in the beginning.

Poitras: Well, in my case, actually when I started the editing, I didn’t know exactly what would be the structure. I had this idea of many experiences of the night. There is not just one night; there’s yours and mine, and each of them are different. We saw associations of feelings, association of situations that would help the editing. But i didn’t want the film to rely on characters, so there would be huge spaces for the audience to to project their own experience in the film. So that’s why you go into a room, you see something, you go out. You don’t stay with these people. You see some people sleeping with a baby, but these are just little experience that may trigger memories of people in the audience, that’s what I wanted to do. I need some place to be obscure, not understandable to everybody, not open to everybody. And, for me, night is another form of that.

PP: Which ties into the quote at the end about dark energy…

Poitras: Yes. That makes the three-quarters of the universe…

Handal:Yes. You said four percent of the…

Poitras: Of the universe is made of dark energy and from which we don’t know anything…about which we don’t know anything. I thought that it’s important to bring back these ideas, that we don’t have to control everything, to know everything.

Krüger: As long as the viewers is taken somewhere to a certain place and he wants to watch further, that’s enough basically. It’s very refreshing to know that there is a meaning which we didn’t know of before, and that neither the editor nor me, we exactly know what we are doing. We know that there is a meaning, because we feel it works, the material say it works. If we don’t, we cannot actually express it or define it in words why or what is. That’s very good because that means that we have created something; it was not predicted or foresee before or something. And that, for me, is the essence of creativity.

Handal I’m quite interested in the idea of a moment containing the traces of other moments so that way you can create the threads. In the beginning when you’re perhaps watching something you’re not aware of but at a later moment, it starts to have new meaning. So, for me, it just stayed really when you mentioned ‘train’ earlier. I said to myself, “Wow.” It’s amazing, the image of a train because train has this idea of freedom and the ability to go places and this was actually…the sound was actually of a place that walking into a barrier [a border fence]. And so, you actually can’t move. How do you bring it back to the human stories – the stories of loss or pain – things that everyone can relate to in a way. For me, looking for that language, the visual language, the tensions, those small moments, this was, for me, the whole work.

Regions: Canada