Filmmakers and Their Global Lens: Inuk Silis Høegh

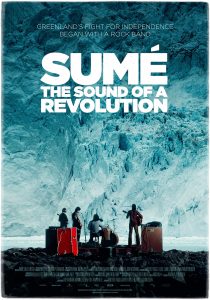

Dana Knight speaks with Inuk Silis Høegh about the first ever Greenlandic Film at Berlinale

Inuk Silis Høegh comes from an acclaimed family of artists, his father is famed photographer and videographer Ivars Silis and his mother is Aka Hoegh, one of Greenland’s most prominent artists who is often cited as being one of the originators of the country’s independent artistic identity. Staff Writer Dana Knight spoke with Silis Høegh at Berlinale in early 2015 about his work, SUMÉ – The Sound of a Revolution.

Dana Knight: This is a very special project being the first Greenlandic film to be selected at Berlinale, could you please introduce the film and tell us how it came about?

Inuk Silis Høegh: SUMÉ – The Sound of a Revolution is the story of the first Greenlandic rock band and its huge impact in the new awakening of the Greenlandic people in the 1970s. A protest against the Danish rule and a revolution of the hearts and minds that ultimately led to Greenland obtaining a Home Rule Government in 1979.

My creative producer Emile Peronard got the idea for the film. I have always thought that Sumé’s music’s impact on Greenland could make a good story for a film. So when he wanted me to cooperate with him in making it into a documentary I didn’t hesitate for a second. Here was a very talented and dedicated guy wanting to work with me on a story about a cultural awakening in my country. And it would turn out to be a perfect timing for such a film, here around the 40th anniversary of Sumé‘s first record Greenland is again in the midst of a debate about values and identity.

DK: SUMÉ seems to occupy a very unique place in Greenland’s musical and social history, having had a great impact on the mentality and lifestyle of the time. Could you explain in what ways?

Silis Høegh: Among other issues Sumé‘s lyrics put feeling of alienation, loss of direction and the reestablishment of own self-esteem into words and questioned peoples indignation towards authority. I think all of those issues are just as much in play today as they were 40 years ago. Yes, a lot has happened since the cultural revolution in the 1970s. Power has shifted, but the Greenlandic people as a separate modern nation has only just started shaping itself. And where Sumé‘s lyrics were indirectly criticizing the Danish rule, that criticism seems just as relevant towards our own political leaders of today and towards the economical powers.

Silis Høegh: Among other issues Sumé‘s lyrics put feeling of alienation, loss of direction and the reestablishment of own self-esteem into words and questioned peoples indignation towards authority. I think all of those issues are just as much in play today as they were 40 years ago. Yes, a lot has happened since the cultural revolution in the 1970s. Power has shifted, but the Greenlandic people as a separate modern nation has only just started shaping itself. And where Sumé‘s lyrics were indirectly criticizing the Danish rule, that criticism seems just as relevant towards our own political leaders of today and towards the economical powers.

And with globalization and the requirements for different qualifications the citizens are not as homogenic a group as before. I think the basic discussion of values and identity as individuals and as a people that Sumé‘s lyrics were an important part of, is as important than ever before.

DK: Where does the archival footage come from?

Silis Høegh: Back in the 1970s there were no Greenlandic TV channels or Greenlandic filmmakers. We knew this, but were still quite shocked at how little footage of Sumé we found in the research. Even still images turned out to be very few and mostly point-and-shoot images made by amateurs. Cameras were an expensive hobby and it turned out that almost no young rock listeners could afford it in Greenland back then. So the footage we could find was from Danish archives – foreign film crews on short visits to Greenland. And there was not one single film clip of Sumé in Greenland! So we were actually working with the idea of using new footage to mirror the past, as the band – now all around 60 – was playing again.

But Emile’s grandfather – who was the first Greenlandic minister of Greenland in the Danish government in the period of Sumé – had shot some 8mm footage on his trips to Greenland. It was a Greenland we hadn’t seen before.

We then started to ask around for 8mm home film footage from people’s attics and basements. And even though we only found a couple of minutes of worn silent footage of Sumé playing an outdoor concert in Greenland, we were fascinated by some of the scenes of life in the 1950s – 1970s. We tried to think of ways to incorporate silent footage of Greenlandic everyday life from the period of Sumé.

DK: How did you approach the material, the film has a free-flowing quality to it.

Silis Høegh: I am not very structured in the way I approach my art. Even though I like to script things and ideas quite thoroughly to have a set frame, I work more intuitively with collected material. Fortunately Emile has this detective gene so he was very good at digging in archives and collecting a good pool of possibilities for us to work with.And then we were lucky to get a really fantastic editor Per K. Kirkegaard on board who saw the potential in the previously unseen footage. And by trial and error, and with the help of Sumé’s music and lyrics we found a way to use this previously unseen footage shot by amateurs, a more unfiltered intimate look into peoples’ lives. It turned out to be real gold for our project.

DK: What were the challenges of putting together a film like this?

Silis Høegh: The lack of footage from Greenland in the 1970s called for creativity. The 8mm film had no sound so we couldn’t use it as reportage footage. But in the end the solution of making the music resonate with these images was the key. Also the story takes place in two different countries far apart – Greenland and Denmark – and in two different time periods – the 1970s and today. So the challenge was to make an engaging story without having to make a history lesson and also not confuse the viewer by jumping in time and space too much.

DK: Where did you find funding?

Silis Høegh: We wanted it to be a Greenlandic film even though the funds for filmmaking in Greenland are minuscule. But we got a lot of support from local funds and managed to raise half of the budget at home. We then looked towards the Nordic countries and made it a co-production with Bullitt Film in Denmark and Jabfilm in Norway. In this way we were able to get co-production funding from the Danish and North-Norwegian film institutes and from the Nordic Film and TV Fund. And we also pre-sold the film to DR in Denmark, SVT in Sweden and NRK in Norway. All in all it was all about finding our way in a new territory as the first Greenlandic documentary film ever to do international co-production. And when we needed more editing time than budgeted, Emile had to be really ingenious to find the lacking funds and we put quite a lot of our own money into finishing the film.

DK: How did you get into filmmaking? Did you go to film school?

Silis Høegh: I have always had an interest in cameras, I was a cameraman filming handball matches at the local TV station as a teenager but didn’t think much of it. I got into filmmaking after a detour in Media Communication Studies in Denmark. It was quite a revelation to realize that I wasn’t satisfied with analyzing media campaigns using cinematic language but that I wanted to create myself. My parents are artists and I always thought I wanted to be something completely different. So I got accepted for a MA Filmmaking course at the University of Bristol and found myself buckling my safety belt in taxis because I didn’t want to die before I got to film school.

DK: What is Greenland’ film scene like at the moment?

Silis Høegh: Greenland’s film scene is quietly exploding although the first feature film produced and directed by filmmakers from Greenland really only just came about six years ago. And now the first feature film ever from Greenland at the Berlin Film Festival premiered. And seven directors presented their work at a reception at the Berlin Film Festival, backed up by Greenlandic government funds. As smaller and cheaper cameras came out, it became possible to get going easier, but the sparse infrastructure and the wild climate still present big challenges so sometimes I don’t know how we manage to finish films on these really minuscule budgets.

But our hope is to find more international cooperation in the future, to learn and get access to funding abroad – maybe we can use the fact that we are so far away from the rest of the world as an advantage.

DK: What are your film influences?

Silis Høegh: I watched a lot of Chinese films when in film school and enjoyed the way Zhang Yimous told universal stories with a hidden criticism towards the Chinese system while balancing the threat of censorship. And I love Wong Kar-wai’s visual style and poetic intimacy.

But I’m really a sponge, I like most well-told stories. And for example I loooove Apocalypto by Mel Gibson. An action movie set in the ancient Mayan culture and in their own language. Maybe because I feel some sort of kinship with an unspoiled indigenous people living close to nature. It wakes a feeling in me of being a son of the earth.