Examining the ‘Ripple Effects’ of War Through “My Father’s Vietnam”

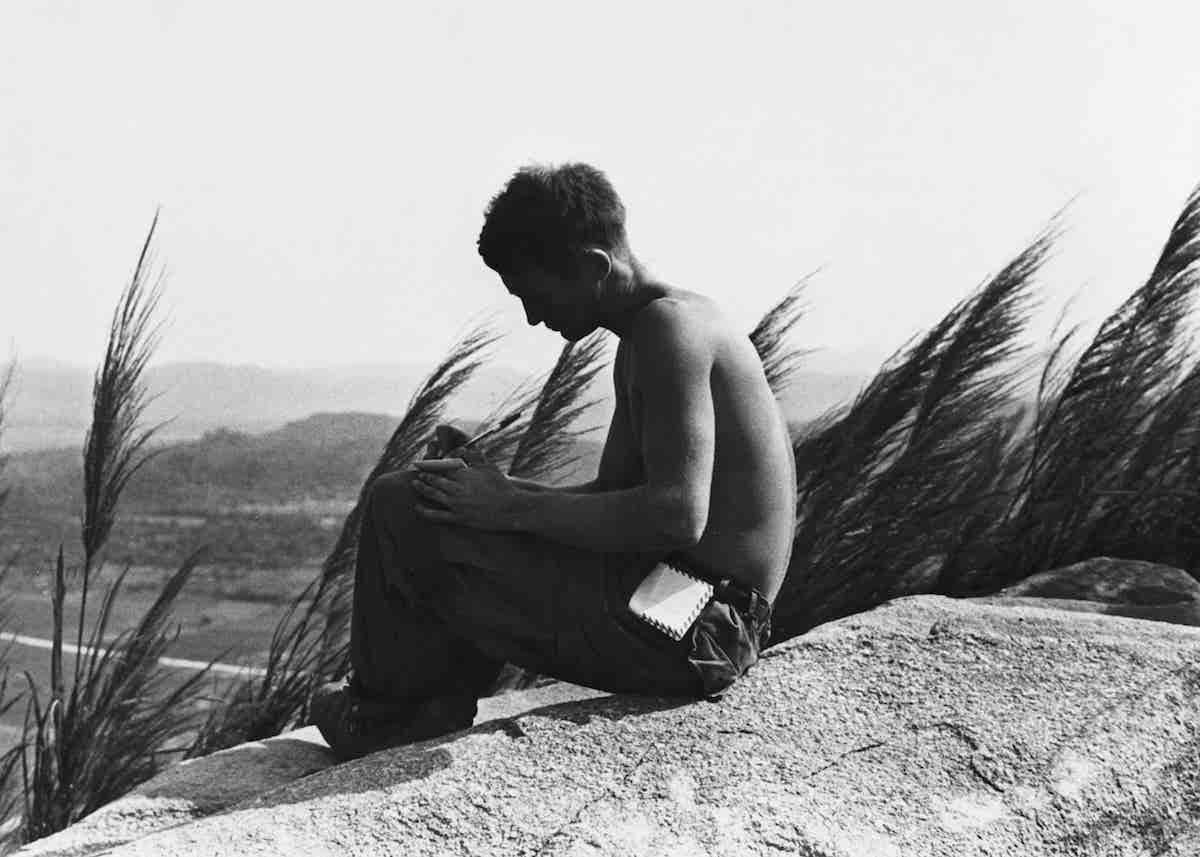

Filmmaker Søren Sørensen recounts what prompted him to explore the Vietnam War's impacts on his father, other veterans, and us all.

My father was a Vietnam veteran.

My father is a Vietnam veteran, though you wouldn’t know it to look at him. He doesn’t have the baseball cap, the button, or the bumper sticker. He doesn’t have the license plate or the license plate frame. He doesn’t have any army buddies or a military-themed tattoo. He’s never been suicidal or dealt with addiction. He’s not a cliché. He’s not what I thought of as a typical Vietnam veteran when I was growing up.

With hindsight, I realize how foolish it is to conjure the typical member of any group, let alone one of the more than 2.5 million who served the United States inside Vietnam’s borders between 1965 and 1973. For many, the Vietnam War began well before 1965 and, for many more, it lasted well beyond 1973. My Father’s Vietnam, a documentary film about my father and two men with whom he served who were killed in action during the conflict, represents an attempt to better know both my parents and to understand their life together a few short years before I was born.

When my sister and I were children, our father’s military service was not off limits as a topic of conversation. It never came up unless we brought it up, which we never did. I like to picture my family sitting around the dinner table in our suburban home 25 years ago, when I was 16 and my sister was 10.

“The chicken is great,” my father might say.

“You think so? I think it’s dry,” my mother would reply. “Can you pass the peas?”

Then maybe I’d ask, “Dad, when you were in Vietnam, did you ever kill anyone?” or, “Did you know anyone who was killed?” or, “Did you almost get killed?”

I didn’t know how to ask. I didn’t know what to ask.

My father was not closed off or emotionally unavailable to me. He would have answered my questions if I had bothered to ask them. But the Vietnam War always felt like a terminal illness. We just didn’t mention it. I didn’t ask and he didn’t tell.

I knew he had stories. I have a clear memory of him making pencil rubbings of two names, out of the more than 58,000 etched into the granite wall at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, DC. I vaguely recall bragging about my father’s military service to classmates, dispassionately peppering conversations with throwaway lines like his friends got killed, he has permanent hearing loss, he doesn’t talk about the war. I imagine I’m not the only person who as a child publicly celebrated the mundane aspects of his parents’ lives. My father (like everyone else’s father apparently) knew everything and could do anything. I once told a local newspaper that my mother was “cool” because she “liked rock n’ roll.” It’s embarrassing to think about now.

As a teenager in the late 1980s and early 1990s, I didn’t think much about the Vietnam War, much less my father’s participation in it. I knew that he enlisted — that he was not drafted — and this disturbed me on some level. According to every opinion to which I had access, the Vietnam War was, to borrow the title of Thomas E. Ricks’ 2006 book about the Iraq War, a “fiasco.” On the other hand, I felt drawn to the 1960s in ways that a lot of my peers were at that time — sex, drugs, rock n’ roll, peace, love, music, etc. Pick your slogan. I started to play the guitar. I got a Jimi Hendrix tattoo. Years later, comedian Ricky Gervais would perfectly distill the Vietnam War’s dubious distinction in two words: “Best soundtrack.” I read somewhere that people often feel drawn, as I was, emotionally and intellectually, to the decade just preceding their birth.

My father loves film and film music. When I was growing up, only his Rolling Stones albums outnumbered his movie soundtracks. My earliest memories of cinema are of my father taking me to the movies: a lot of war, politics, and history for a young person to absorb. In the 10 years between 1985 and 1995, the filmmaker Oliver Stone released 10 films, six of which are set in the Vietnam era: Platoon (1986), Born on the Fourth of July (1989), The Doors (1991), JFK (1991), Heaven and Earth (1993), and Nixon (1995). If we didn’t see one of these films in the theater, we rented it on VHS. Now, as if to emphasize the passing of time, a theme central to my own film, video stores are nearly as extinct as the videotapes that used to fill them.

I can’t think of another period of American military adventure, to borrow again from Mr. Ricks, that has produced as vivid and immersive a cinema as the Vietnam War. Michael Cimino’s The Deer Hunter (1978) Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (1979), Mr. Stone’s Platoon, and Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket (1987) all spring to mind. Given the creative and technological development of music and movies in the 1960s and 1970s, the lasting impression left by films of and related to the Vietnam era isn’t surprising. Many of the people who inspired the characters in these movies are still with us. Vietnam veterans like my father mirror, echo, and expand the enduring appeal of Vietnam War films.

Looking back at the years leading up to the 2006 conversation with my father that would eventually become the basis of my film, four things spring to mind.

Firstly, I remember following the 2000 presidential election more closely than any other I had lived through up until that point. I suppose this makes perfect sense – by 2000 I was 25, I was a college graduate, and I had developed some political opinions. These opinions were basically indistinguishable from those of my parents, but they were opinions nonetheless. Quite aside from one’s feelings about that election’s outcome, its aftermath was a free civics lesson and made for great television. Remember Tim Russert’s dry-erase board? America in 2016 is again experiencing another in a long series of “most important” elections in our nation’s history. If each election cycle wasn’t more important, divisive, contested than the last, voters could lose one or more of the cable news channels we rely on to complain about every four years.

Secondly, September 11, 2001 – coordinated attacks so unusual they’re known only by their shared date –captured and held my attention in a manner I expect is not unique to me. I attended the funeral of a colleague who was on one of the two planes that destroyed the Twin Towers in New York. I visited a Coast Guard recruiter in Boston, ultimately feeling too old and too fat to pursue selective service. I stuck an American flag sticker to the back of my car, and occasionally eschewed National Public Radio for Jay Severin’s conservative call-in show.

Thirdly, my move from Boston to New York City one year, almost to the day, after 9/11 had a major impact on my creative development. I was a production assistant then, working on television commercials mostly, and New York seemed like the next logical step. But it wasn’t my zip code or New York’s aesthetic allure that left the biggest impression – it was the fact that my roommate, Dan Akiba, was in film school devouring the work of filmmakers like Alan Berliner, Nick Broomfield, Werner Herzog, Ross McElwee, Albert and David Maysles, Errol Morris, D.A. Pennebaker, and Frederick Wiseman. Whenever he brought a stack of films home to watch, I’d try to watch as many as I could. My film owes its title to Mr. Akiba — My Father’s Vietnam is a not-so-subtle homage to his short documentary, My Brother’s Wedding (2003), which involves the story of his secular Jewish family traveling to Israel to attend the wedding of his ultra-orthodox younger sibling. I would never have made My Father’s Vietnam had it not been for the films, including his own, to which Mr. Akiba introduced me.

Lastly, I felt adrift. I had just experienced a breakup and was seeing a psychologist. Anyone who has had what they consider to be a successful experience with talk therapy knows it has the tendency to act as a mirror. I expressed a desire to ask my father about his military service and my therapist responded, “Why don’t you?” It seemed so simple. Given Mr. Akiba’s expertise behind the camera, ongoing wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and my growing interest in politics and civics, it was time to break a decades-long silence.

My Father’s Vietnam is the culmination of several years of work. Production was a walkabout of sorts, spread out over five years. When we could afford it, Mr. Akiba and I would travel from Brooklyn to Arizona, Connecticut (where I was born and raised), Florida, Pennsylvania, or Vermont to ask total strangers about some of the most painful experiences of their lives.

In some shots I’m driving alone or walking with someone I had just met for the first time that day. In others I’m absent, the landscapes of places I’ve never visited passing me by for the first and possibly last time. In either case, the film’s depictions of physical movement — often to and from airports — will hopefully evoke visual elements commonly associated with “road movies.” While certainly less rambunctious than Easy Rider (1969), My Father’s Vietnam aspires to evoke the same sense of urgency, disorder, and ambiguity. Deliberately relaxed and understated, My Father’s Vietnam contemplates the “ripple effects,” as my father puts it, of war in a broad sense and the Vietnam era specifically.

In shooting and editing the film, it helped to visualize that ripple metaphor, those expanding concentric circles created when a pebble is thrown into a body of calm water. Films made during and in the immediate aftermath of the Vietnam War represent the sudden splash! of the pebble’s impact, chaotic and disruptive. My Father’s Vietnam represents the quietly fading but ever-present outermost ripples of Vietnam’s impact, as the water continues to be troubled by fresh disturbances – Iraq and Afghanistan – the effects of which we have yet to fully grasp.

Claude Choules, who served in the British Royal Navy during World War I, passed away in 2011, aged 110. Until his death, Mr. Choules was the last WWI veteran alive. It’s strange – I don’t know a thing about WWI. And the image I once conjured of the typical Vietnam veteran depended largely upon a collection of films I still adore despite the broad range of exaggerations and omissions, from the subtly artistic to the savagely inaccurate, they exploit for better or for worse. Proximity to my father – throughout my life and during the making of My Father’s Vietnam – debunked my perceptions not only about him, but also about my friends’ fathers, Paul Daley and Israel Mechlowicz among them, and every other Vietnam veteran I encounter as a result of my film. Without that proximity, there would be no film.

Eventually the last Vietnam veteran will die — perhaps after my own life has ended. Claude Choules was born on March 3, 1901. Peter Sørensen, my father, was born on March 3, 1946. If my father lives to be 110, an age he doesn’t expect to reach, I’ll be over 80, an age I don’t expect to reach. In other words, life is (usually) short. My father makes it very clear, to me privately and in his interactions with audiences of the film, that he doesn’t believe his story to be especially unique. I understand what he means. It’s not false modesty. Everyone experiences life and death. We’re all obsessed in one way or another by matters of life and death, youth and old age, and the passage of time. Anyone who has considered the process of aging and mortality or experienced the death of a friend or loved one, regardless of the circumstances, has hopefully experienced the boundless love and compassion of which individual citizens and communities are capable. As Vietnam veterans reach the ends of their lives, we might consider preserving more than just their heartbeats. We might set aside some of our precious time together to draw out the memories they have just beneath the surface of that rare experience of going to war, where life and death are near enough to one another to be virtually indistinguishable.

My Father’s Vietnam is available on Blu-ray and DVD on September 9, 2016.