New Doc Explores Benefits of Restorative Justice Practice

Marie-Emmanuelle Hartness interviews Director Julie Mallozzi on her new film Circle Up

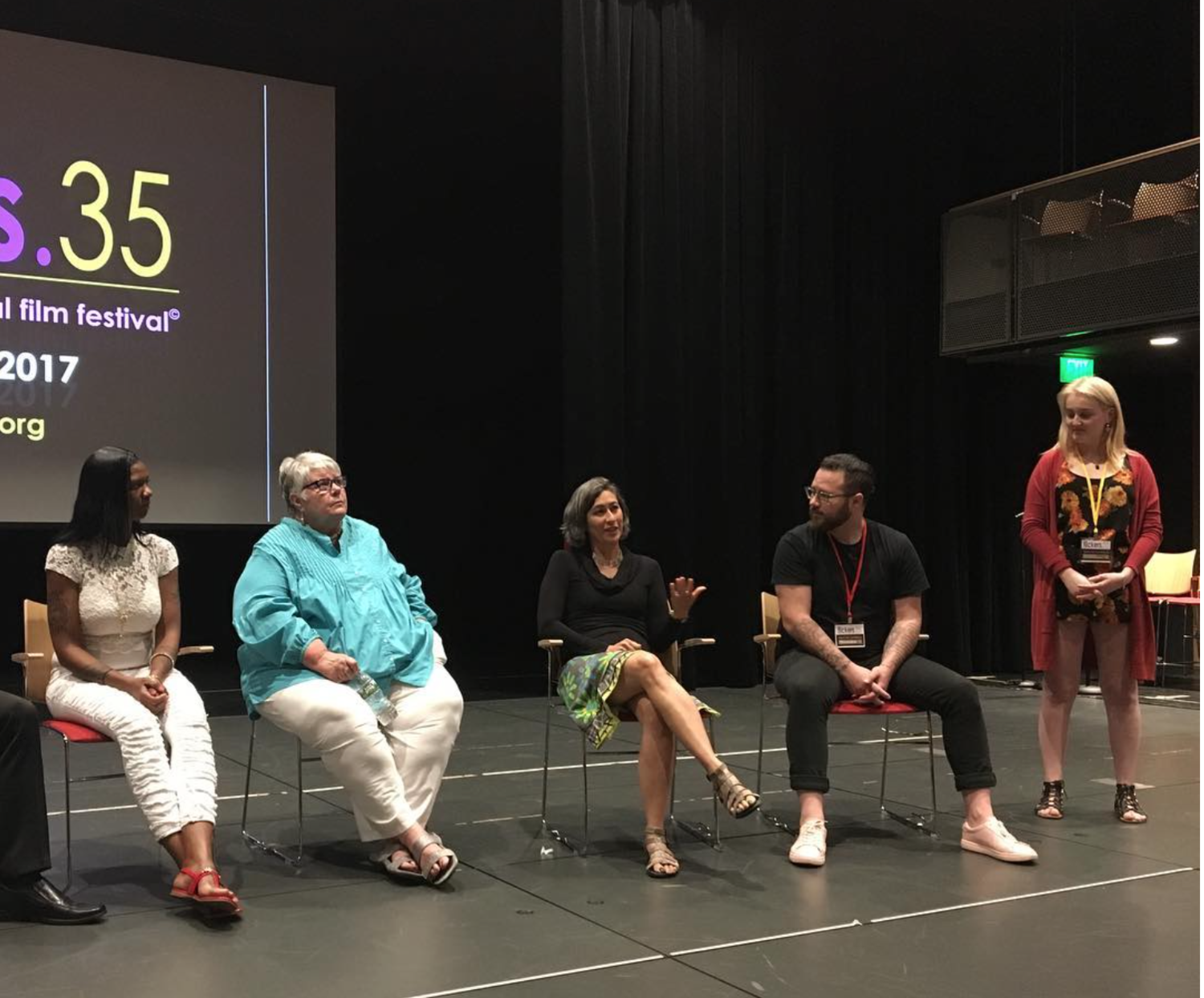

In Circle Up, Boston-based filmmaker Julie Mallozzi explores the power of peacemaking circles in restorative justice. Peacemaking circles are a traditional form of justice-based restorative practice that originates in many Native American cultures. Circles, in this context, are arrangements that provide community members a means to discuss and resolve conflict. Individuals take turns expressing themselves in a non-adversarial way. In Circle Up, Julie follows Janet Connors, a woman who practices circles to cope with the murder of her son and to help parents survive loss and reach the otherwise improbable state of forgiveness. Janet teams with Clarissa Turner to organize circles for parents and young kids exposed to crime. One of Julie’s subjects, Ismael, is an eighteen-year-old boy who does not expect to live past 21 because of the violence that has plagued his community and peers. Through peace circles, Janet and Clarissa give hope to Ismael and his friends. They help them envision going to college, getting a job, becoming parents, and breaking the mold of inevitable violence. I met with Julie after a highly emotional screening and Q&A at the Brattle Theatre in Cambridge, as part of the Globedocs Film Festival.

In Circle Up, you explore the power of resilience and personal journey, but you also open a dialogue on justice and forgiveness through peacemaking circles. What drew you to making a film on restorative justice?

I was originally drawn to the cultural practices of peacemaking circles which is an indigenous tradition that is used to help resolve conflict, build communities, and heal after harm has been done. It is used in Native American culture but also Maori culture and some indigenous African cultures. This tradition is simple but different from our kind of modern western way of living because it puts everyone on an equal footing, and it allows people to speak and listen, with empathy, to everybody else before they speak. Ten years ago, I heard about this practice, and I liked the idea of a Native American ritual being used in an urban setting to prevent gang violence. So, I started doing research and filming circles around the country. In the meantime, I was doing my film Indelible Lalita, so it took me five years of gestation while I made this other film, to find a story. Five years ago, I met Janet Connors; that’s when it became her story and her personal journey and her use of the peacemaking circle. It was no longer a topical film about circles; it became a life story about forgiveness, accountability, and justice. And it expanded beyond Janet to some other mothers.

In previous circles you filmed, which issues were your subjects working on resolving?

I received some funding from Mass Humanities to travel around the country, and I discovered peacemaking circle practices in schools in Oakland, California. They are trying to find alternatives to punitive systems and to suspending and expelling students in order to end the school-to-prison pipeline. Because being cast out from the community doesn’t help the kids or the community at all, so they replace that with a restorative justice system. They use the peace circles to build community in the classrooms against bullying and to resolve conflicts between teachers and students. I also observed a support group in Chicago using Spanish-speaking circles for people who have lost loved ones to homicides. When I first attended, there were three new parents whose children had just been murdered, and there were new people showing up every couple of weeks–raw, on the battlefield–and the support circle would help them get through that.

Are there mainly mothers attending these peace circles?

There is a movement among mothers, and I have a short version of the film that I’m showing to some community settings. This week there is a conference in Boston called Mothers for Justice and Equality; the women gathered have all lost children to homicide. They have assembled from across the country and are working to heal from this trauma. They are all fighting for peace, anti-violence, and gun control. I will be doing a workshop on storytelling and social change. It’s so meaningful to me to bring my film to an audience of 100 people committed to a peaceful response to violent crime. My aim is to help them amplify their stories and make a change in their communities. It is different than an art project; I guess it’s more of a social justice project.

But it is through the art form of filmmaking that you engage the community.

Yes, and the film has become a training tool for people.

How did this project affect you as a woman and as a mother?

It was very deep and was more emotionally moving than other films I’ve worked on. It was great working with my editor Shondra Burke because she is very good at getting at the emotion. I also learned to work with trauma survivors, something I had not done before. It was a really different process. For example, it’s not easy for Janet to be in an audience and watch her son’s blood appear on the screen, not once but twice. We had a conversation about whether she could handle being in the film and about what it means for someone to see a loved one in pieces, dead on a big screen, and having to keep reliving this experience in interviews. And for young people, there is a risk of being re-traumatized; if their cousin was just murdered a few days ago, their wound is still completely open. It was very delicate. I didn’t want to come as a filmmaker seizing their story and thus cause more harm. We collaborated and made sure their stories were respected, they were part of how their stories were told.

What was the impact of filming on the community members? In what way would you say that filming helped with the healing process?

Being in a film definitely affected the moms and probably also Ismael, the main kid I interviewed, but I think the circle would have proceeded that way whether I had been filming or not. But the idea that other people will see you, together, in a peace circle—that made a difference for Janet and the other moms. Their stories could be seen beyond the circle and help more people. Their stories had suddenly more power and value that way.

You usually film on your own, but this time you had a camera person and more collaborators. What changed in your filmmaking process?

Yes, I have always shot all my other works. I was trained with a small core of professors at Harvard and a cohort like Allie Humenuk, Amanda Micheli, and Nina Davenport. Our teachers were our heroes: they were filming, editing, taking their own sound, and we were taught that way. We had a DIY kind of pride, but things have changed, and even our mentors don’t do it that way anymore. I’ve been working with Shondra and Thomas on freelance projects, so it felt like a very natural process to work together on Circle Up. I would always be on set; Thomas would film and I would take sound or the other way around.

How did you produce this film? You said you had a grant originally?

I had a couple of very small grants. There was a crowdfunding campaign and a lot of working for free. It is a typical story of an independent documentary! I’ve had previous works where I have raised public television funding, so I was able to pay myself and all the expenses but it was not possible with Circle Up. I hardly earned any money; I invested some of my own money, and we did a very extensive crowdfunding campaign. We raised $54,000 with Indiegogo. We received funding from Mass Humanities, a little bit from LEF, a little bit from the Center for Restorative Justice, $1000 from a Mass Media Fellowship, a RISD grant… very small amounts of money. And that’s why it took me five years; if I had had more funding I think it would have taken me three. I’m not the only one with this problem. I feel like it is getting harder and harder. There is so much competition and as a mother trying to be an artist, to make a living and to be a good parent is a challenge. To try to do those three things feels like being 150%, being a superwoman!

Lalita, the subject of your previous film, came all the way from Montreal to support your premier in Boston. Do you stay close to your subjects beyond the making of the film?

We naturally become friends in the process. I was trying to get the Monkey Dance kids to come too, and I’m actually making a little follow up film on the Monkey Dance kids, 15 years later. When you spend five years with people in an intimate context, you naturally become friends with them and you keep in touch.

This is an important and timely film, what is the outreach you’re working on?

I’m partnering with the Center for Restorative Justice at Suffolk University. They are coming on as a lead organizer, which is great because I’m just a filmmaker, and I want to make another film. I don’t want to spend next five or seven years only distributing this one. Also, I’m not a restorative justice practitioner with tons of contacts in the field, and they are. So we are working on some pilot projects, for example to get the film to juvenile justice facilities in Connecticut and get the film showing in prisons. If you can get the prison system or probation or juvenile justice system or a whole school system to integrate into curriculum, then suddenly you can have 50 screenings all at once and 30 very highly affected people who are target audience.

Do you see this film as appropriate for all ages? I noticed your daughters were here, but I guess they been through the process of your film for a long time.

I talk to them, actually, I asked them if it should be restricted to kids above seventh-grade or eighth grade. I think it depends also if the kids are living in similar circumstances, they could see it at a younger age because they are exposed.

How was it to work with your husband on the music?

I am really pleased with the results and the process of the music was very cool. In my previous films, he composed. This time, instead of writing it all out, he improvised. He thought about the textures we wanted. He brought some baselines and a few melodic lines, but he let the musicians primarily improvise. We went to our friend who has a recording studio in a barn; we played sections of the film and they would be improvising to it. We recorded the tracks, so we could edit them in. Since the film was still being edited, we had to do mini adjustments. But, I’m very happy on how it came out.

What is your distribution plan for Circle Up?

This kind of project really spreads by word-of-mouth, especially this one because I’m aiming not just at the usual television but also at community-based screenings. It doesn’t have to be just people affected by crime and violence; forgiveness and justice are everyday concepts that we all struggle with. I hope people can look it up on social media, through newsletters, and pass it along so that it can find its home.

You mentioned at the end of the Q&A that people could interact with Circle Up by filming short personal clips?

We are starting a little social media flurry on people speaking for up to a minute about forgiveness, justice or accountability. We are organizing by the hashtag: #circleupdoc. We have been filming people after screenings. We are also setting up an online kiosk on our website where people can click on a button and record a clip to be automatically fed to social media. We are envisioning something bigger than just the film itself: an ongoing conversation on justice, forgiveness and accountability.

Regions: Boston