Hollywood Was a Matriarchy

The Forgotten Decade of Women’s Power and Independence in Film

Kerry McElroy writes about Female Resistance at the Film Industry’s Dawn in this first series installment of Bette, Marilyn, and #MeToo: What Studio-Era Actresses Can Teach Us About Economics and Rebellion, Post-Weinstein

We are almost at the year anniversary of the first #MeToo reverberations in Hollywood. All of us, from creative professionals in film industries to film journalists and scholars, women and men, are reckoning with the shifting spheres of culpability and power following last year’s cataclysm of scandal in the film industry and beyond. The #MeToo movement of the fall is beginning to bear fruit. Signs are emerging that activism may, in fact, finally, translate into real sustainable change after a century of exploitation of women as the filmic static quo. A-list creative women are helming Time’s Up, an advocacy group against sexual harassment in the industry. Multi-million dollar legal aid funds are emerging. Even a high profile commission, supported by Anita Hill, has been formed to contend with what precisely has been going on in this business for so very long.

In this climate of truth-telling and investigation, independent film must not be overlooked by any means. Just as reverberations of this sea change have been felt in the worlds of theater, fashion, music, and media, independent filmmaking’s status allows for no assumption of innocence in terms of gender abuse. What greater proof is needed than to recall the decades-long touting of Harvey Weinstein as “the king of the independents”? In this cultural moment, we are obligated to look to moral culpability in all types of filmmaking throughout a century of cinema—not to look away or place blame elsewhere.

At the same time, there are positive approaches to be taken, when we are willing to stretch beyond traditional definitions of what “independent film” actually can mean. I propose that we as writers, filmmakers, and scholars use this moment in part to reconnect with a long history of women carving out spaces of independence within decidedly non-independent film. We can do this via film history—resurrecting, revitalizing, and giving credence to long-buried and ignored tales of women’s places within Hollywood film. Whether we choose to face this new era with economic revolt, political agitation, or labor organizing, film history can serve as a vehicle for this moment. Such use of history via memoir and interview implies that writers and scholars who research women in Hollywood can serve as real allies to women working in the business today, providing them with historical evidence that bolsters #MeToo and Time’s Up.

Now more than ever is the right time to go back in the historical record, and find instances of women’s large and small rebellions within film, against huge obstacles in both institutional film and the larger patriarchal culture. Within this broader project, the reasons for beginning at the beginning—the 1910s—are twofold. The first is that a comprehensive chronology is a natural way to explore the positions of women in film across a century, the good and the bad. The second is less obvious but more interesting. An armchair historian might assume that if we trace the history of women in film chronologically, from its beginnings through the decades, we will find a system that reflects the evolution of history that oppressed women most severely early on and less so with each passing decade. Such a teleological view, one that sees the march of history as the march of progress, is nearly always proven false. With a little digging into the historical record, we find, surprisingly, that the 1910s were quite revolutionary for women in film, with a utopian feeling of unlimited promise. It took the tightening of male corporate control in the next decade to end up with the misogynist problematic we know so well today. As the radical creative and gender possibilities of Hollywood’s 1910s were swept under the rug, a space where men could rule with an iron fist over casting decisions, body type, contracts, and sexual availability was fully enacted. One might say we are only just now, like both industry and scholarly Rip Van Winkles, finally coming out of that century-long stage. A return to the 1910s to discover and name women’s independence in film is, of all times, particularly in order.

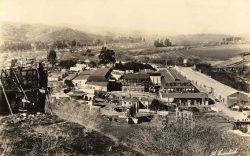

In this excavation, we should be particularly interested in the establishment of Hollywood as the first city in the world built on performance. By 1920, in a massive and rapid migration, 85% of films in the U.S. were being made in Los Angeles. In press write-ups, LA was billed at city of the future, an entertainment hub, alive with new technological and artistic possibilities. One 1913 Universal Weekly headline summed up the feeling of the moment: ¨Where Work is Play and Play is Work: Universal City, California, the Only Incorporated Moving Picture Town in the World, and its Unique Features. ‘Movie’ Actresses Control Its Politics” (qtd. in Cooper 8). The image evoked was one of a futuristic playground where seemingly anyone, but especially women, could make something unique of themselves. Adela Rogers St. John is emblematic of this spirit of liberation and the “New Woman” in the “new city,” when she writes that the early Hollywood of Pickford, the Gishes, and the Talmadges was a matriarchy (qtd. in Hallett 43). Similarly speaking of this 1910s era, screenwriter Lenore Coffee remarks, “Remember this was the day of women” (qtd. in Hallett 57). This metaphorical day included not only women performers, but women directors and a large number of women screenwriters as well.

While women filled a number of industry positions at this time, it was the day of the actress most of all. From the plucky proto-feminist Helen Holmes in The Hazards of Helen to the demandingly physical stunt work of Gene Gauthier and Pearl White, the actresses of the 1910s projected a powerful, middle- and working-class feminine courage. Above all, they infused the global New Women with a front-and-center Americanism that reverberated around the globe. These women became international stars, depicted on the covers of fan magazines in scores of languages and on every continent. To international audiences, critics, and intellectuals alike, these women represented an American physicality and bravery. America appeared to be a kind of gender utopia on-screen, and Hollywood seemed to be one too.

Indeed, the emergent city of Los Angeles was ideally suited for independent women. In what was still, relatively speaking, an independent film industry, L.A.’s geographic and industrial space allowed newly-arriving young, modern women to live independent and in a fresh way. This possibility influenced many thousands of young girls to take part in the migration to L.A.—not only from around the U.S., but from around the world. Film and cultural historian Hilary Hallett has written about Hollywood’s “feminization of western migration,” noting that the new situation in which “female migrants outnumbered male ones… effect[ed] a ‘stunning’ reversal in western migration patterns” (Hallett 11). Going against all traditions of the western boomtown, Los Angeles had—seemingly overnight—become a uniquely more feminine place than any other western city. “‘There are more women in Los Angeles than any other city in the world and it’s the movies that bring them,” one shopkeeper bluntly asserted in 1918 (Hallett 12). Further, one in five of these new women were divorced or widowed, making them a relatively older and more experienced demographic than traditional female urban migrations to date. These were not country girls seeking service positions, but often sophisticated women looking to start new lives and careers on the West Coast. With all of these seemingly positive factors—how did a business that began with so much promise for women come to be not only just like any other in terms of male capitalist control, but the very symbol of predatory sexual exploitation?

What is certain is that this moment of gender possibility did not last. By 1917, the new industry saw a return to both separate spheres of work and gender norms. Gloria Swanson, arriving to Los Angles in 1916, described a business totally run by men. How did this happen so rapidly? We have to look to the roots of western capitalism, and then on to specifically American capitalism, for the answer. Film historian Jane Gaines has explained the closing of the window for women’s professional independence in young Hollywood as one in which traditional capitalist business models reasserted themselves at the very moment women might have had a chance for real success or independence. In Gaines’ words, “no one knew that motion pictures would become big business. This was not yet a significant industry and with so little at stake (so little power, so little capital), much more could be entrusted to women” (Gaines 105). Institutionalization and corporate organization pushed women out of conversations and decisions they had been a part of just a few years before. Business historian Karen Mahar provides an interesting parallel perspective to Gaines, explaining that when the concern for business legitimacy trumped the concern for cultural legitimacy, this is when women were pushed out of positions of influence within the film industry (qtd. in Cooper 93). We might see 1915 as a watershed moment for this, as the year that the US Supreme Court ruled film a business and not an art. From this point on, according to film historian Jennifer Bean, “the exhibition of motion pictures is a business pure and simple, originated and conducted for profit” (Bean 18). This would have swift and dramatic consequences for women directors, writers, and performers.

To delve deeper, we require an understanding of how the 20th century American corporate model latched on to some ideas of patriarchal pseudoscience to convince itself that women did not belong in business. We can think of the great Hollywood shift of the mid-1910s as patriarchal thinking excused by the “modernity” of Fordism—the early twentieth century glorification of the corporation, the assembly line, and the minutely specific role for each individual worker. In this sort of industrial pseudoscientific thinking, it is of the essence that everyone labors in the precise role suited to them. Women are not suited to leadership roles, so the theory goes, and so it is better to have no women at all than to force women into roles where they will not “fit”. At the beginning, when there weren’t executives per se, women could play. As film became more respectable, conservative, and concerned with profit, experimentation with gender roles was out. Once those with power were cementing a serious system with massive amounts of capital and an executive structure, obviously those executives had to be men.

The flip side of the Fordist unsuitability of women for executive positions is the suitability of women as sexual objects or protected wives and mothers, with no nuance between the two. This reversion to types of women and their available status leads us directly through the entire twentieth century and into today’s Weinstein moment. In this conception (which is far from dead and buried), women had a sphere, and it ought to be the home. If women were around the studio environment than they had better understand the role they occupied—to be sexualized and sexually available. Outside the protection of the private sphere, in an industry that was explicitly public and performative, these women had little reason not to expect exploitation.

Once we understand the roots of misogyny within the emerging film industry, we can understand what the hell has been going on over the last one hundred years. As the earliest days of creative and financial independence gave way to rigid, capitalist, mid-century cultural norms, sexual exploitation was given free reign. Concepts for which we now have a modern feminist vernacular—“slut-shaming” and “victim-blaming,” for example—were not only accepted but became firmly entrenched, legitimate cornerstones of the business. A hierarchy of women was established—of decent women to be left alone, and bad women to be abused in any way that the men in power saw fit—in a kind of droit du seigneur. There was also the implicit understanding that the women who came “out here” deserved what they got for choosing to get involved in the system at all.

While it is not surprising that both Los Angeles, as a new metropolis, and Hollywood, as the site of the new film industry, came to mirror the same racist, misogynist, classist, and capitalist structures of broader American society; the lost potential for a more revolutionary possibility can weigh heavily on historians of the early industry. Speaking to the current cultural moment, criticism of Hollywood as somehow radically left remains an unfounded right-wing talking point. The historical record proves just how false such claims are. Both in terms of content and production, many scholars concur with cultural historian Steven Ross or feminist film scholar Allison Butler in identifying Hollywood as “a conservative popular cinema” (Butler 23). It is now evident that the failure to create a new industry outside of America’s more traditional capitalist patriarchy was intentional, not simply failure of imagination or creativity. In light of #MeToo, we can see how it also led to specifically hazardous industrial conditions for women.

Still it is here, in the period when the Hollywood system solidified, that we find case studies of women who managed to maintain independence, assert financial freedom, or foment creative rebellion. These cases demonstrate that while an indictment of the system is necessary, a pronouncement of women as merely exploited and enslaved is too simplistic.

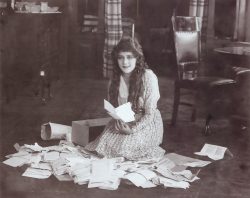

Mary Pickford was the most famous woman in the world until 1925, both a star for twenty years and the “first superstar” at a time when the term was just being coined. The world had never seen her level of popularity; modern global celebrity was a completely new phenomenon. From 1912 to 1932 (fifteen of its first twenty years), Photoplay voted “Little Mary” its number one star. Her ascent to superstardom has been called “the Pickford revolution”— the transforming of a theatrical diva into the recognizably modern global media celebrity. A woman who lived to old age, she wielded great power in the first era of Hollywood and showed real business savvy. Her fame and influence was of such a new sort, in fact, that mogul Adolph Zukor remarked she could have become anything she wanted in life, from president of US Steel on down (qtd. in Hallett 27). Pickford pulled off a hat trick: seen as America’s Sweetheart, she managed to be a brilliant businesswoman (the highest paid in the world) and a supporter of women’s rights without being labeled shrill or militant.

“Are you any better as an actress this week,” he replied, “than you were last week?” I said, “No, sir, but two people recognized me in the subway today. And if I’m going to be embarrassed that way in public, I’ll have to have more money” (Pickford 75).

Throughout her life, in both her publicity and writings, Pickford emphasized the working-class affinity between star and spectator. She declared, “I think I admire most in the world girls who earn their own living. I am proud to be one of them” (qtd. Hallett 70) People were astonished by Pickford’s persistently rising salary. At a time when most girls made $8.00 a week, she made $50,000 dollars a year! The battle to rein in “the power of the stars” was publicly fought, often on moral grounds, and incredibly gendered. The male-capitalist machine of rival studios and publicity mouthpieces in the press often expressed outrage about Pickford’s salary, while of course the earnings of the men who signed her checks went unquestioned. In 1916, Motion Picture Weekly moralized, “When a girl is only twenty-three… yet receiving a weekly salary that is the equivalent of two and hundred and fifty working girls’ wages, there is need of an explanation” (qtd. Gledhill 48).

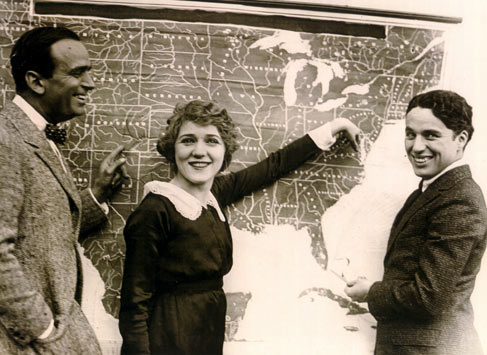

At the height of her powers, Pickford’s recognition of the shift from Hollywood’s earliest freewheeling, egalitarian days to the capitalist-misogynist studio era led her to famously cofound United Artists with Charlie Chaplin and husband Douglas Fairbanks. This seizing of production by the performers themselves was a true watershed moment in Hollywood history. With this, the United Artists group single-handedly started a trend for actresses to seek their own production companies.

Another of the most famous actresses of the silent 1910s, who shared many commonalities with Pickford, was Lillian Gish. Both were launched by and eventually broke away from D.W. Griffith. Both were intelligent, independent, and savvy with money, and both managed long and successful careers despite not fitting the mold of the sexualized and empty-headed actress stereotype. Gish considered herself a professional businesswoman throughout her filmic career, and wouldn’t marry. She declared that marriage is like running a business, and she simply couldn’t do both successfully. In letters to friends at the height of her stardom, she spoke of remaining in the acting profession to give her sister an education and buy a home for her family. Silent era actress turned film history icon and critic, Louise Brooks, once wrote that “it was Lillian Gish who most painfully imposed her picture knowledge and business acumen upon the producers”, describing her as incurring their wrath for her good sense (Brooks qtd Hastie 116). Gish is another actress in the history of Hollywood who managed to forge her own path while maintaining her integrity.

From the late-teens, the system calcified onward, and women were forced to work harder to find economic freedom and self-reliance. The next article in this series will move into the 1920s to look again at moments where women found liberation and autonomy in spite of the system. The 1920s were a paradox: extravagant wealth and star power set against solidifying control and ever stricter norms around sexual (mis)conduct. Even as women lost institutional power, the salaries of a few star-actresses ballooned. Unions were formed. How, precisely, did women carve out independence in the Hollywood film industry of this era? And what can particular scandals (like the 1921 Arbuckle episode) teach us about the current Weinstein moment?

References

Butler, Allison. Women’s Cinema: the Contested Screen. Wallflower, 2002.

Cooper, Mark Garrett. Universal Women: Filmmaking and Institutional Change in Early Hollywood. University of Illinois Press, 2014.

Gaines, Jane. “‘Of Cabbages and Authors.’” A Feminist Reader in Early Cinema, edited by Jennifer Bean and Diane Negra, Duke University Press, 2002.

Gledhill, Christine. “Mary Pickford: Icon of Stardom.” Flickers of Desire: Movie Stars of the 1910s, edited by Jennifer Bean, Rutgers, 2011.

Hallett, Hilary A. Go West, Young Women!: the Rise of Early Hollywood. University of California Press, 2013.

Hastie, Amelie. Cupboards of Curiosity Women, Recollection, and Film History. Duke University Press, 2012.

Pickford, Mary. Sunshine and Shadow. Doubleday, 1955.

Regions: Los Angeles