“The Studio Doesn’t Own Me’’

The Rise of the Tabloids, Studio Fixers, and the Socialist Feminist Wisdom of Marilyn Monroe

Kerry McElroy writes about female resistance in the 1950s for this fifth series installment of Bette, Marilyn, and #MeToo: What Studio-Era Actresses Can Teach Us About Economics and Rebellion, Post-Weinstein.

The previous article in this series focused on, among other things, the impact of prewar international affairs on female suspension practices, legal battles over actress rights, and some forgotten racial history of an underground integrated Hollywood. It also looked at early intellectuals, all women, who began to theorize the treatment of people in the Hollywood system (de Beauvoir; Powdermaker). This article turns to the 1950s, which saw the Hollywood studio system shaken for the first time. It might stand to reason that as the studio system grew weaker, women grew stronger. Not so fast.

Naomi Wolf’s seminal The Beauty Myth (1990) is useful in helping to understand what happened in the 1950s, as entrenched forms of male power weakened in Hollywood. It argues that whenever women begin to assert themselves, then and now—educationally, politically, or legally—capitalist misogyny reasserts itself, forcing newer and ever-more ridiculous standards by which women should live. Wolf has dubbed this phenomenon “the Iron Maiden” (Wolf 17).

This premise is all the more apropos to Hollywood—a place that has always used the illusion of glamour as a cudgel to keep women from revolting against dehumanizing conditions. In the 1950s, the way things had been done in Hollywood for decades was under serious attack for the first time. Ticket sales were down and studio power was weakened by both financial and political elements. The industry responded to these threats from television, shifting culture, and the government not only with hyper-feminine characters and roles, but continued emotional, physical, and sexual abuse of women.

This series has followed Hollywood rebels since the 1910s, but it finds women in the 1950s finally faced with more modern opportunities than simply being exiled from the business for not staying in under total studio control. For the first time, an actress might make a new life abroad without quitting the business entirely, able to return to film intermittently for projects as she chose. Other women were actually able to pursue higher-level education and new professions after their acting careers.

At 33, Ava Gardner was considered “old” in the system and decided to take her chance to move away from Los Angeles, something that would not have been allowed a decade before. As she explained, “All the big companies are making money overseas now….It’s not like the old contract days when you had to get a permit from old Father Mayer to even leave Los Angeles” (Gardner qtd Jordan 128).

Starlet Janice Rule was considered a troublemaker; hence her Warner Brothers contract was allowed to lapse after only two films. Her crime? She was troubled by the body standards and beauty practices of 1950s Hollywood. “Because I was afraid of being robbed of my individuality, I fought with the makeup people, the hairdressers” (Rule qtd Roarke). But what was different for Rule, compared with earlier actresses who left Hollywood often for poverty and obscurity, is that she was able to obtain a PhD and become a psychoanalyst (Ibid.). Even if Hollywood was more determined than ever to hang desperately onto the value of women by bodies alone, the real world was changing.

Still, male misconduct continued or even accelerated unchecked as the studio system weakened and the tabloid press ascended. Since the 1920s, there had been a symbiotic relationship between columnists like Hedda Hopper and Louella Parsons and the studios, with these columnists almost behaving as satellite employees. 1950s media had given way to more kamikaze methods of gossip and information extraction from upstart, shameless outlets like “scandal rag” Confidential. This new breed of Hollywood press sought the salacious, and would print rumors or quash stories for money as they saw fit. The studio system, now weaker, saw the new press as bullies. (Petersen; Canote).

The studios were of course no strangers to salacious methods. For decades a sleazy shadow system of detectives and fixers had been employed to keep secrets and hide crimes. This amounted to a system in which male misbehavior, literally up to rape or murder, could often simply be bought off. Women, by contrast, were frequently intimidated or run out of the business if they threatened to come forward with sexual abuse. 1950s Hollywood was a nexus of the paranoid, witch hunt, McCarthyist climate of the country as a whole- but one in which crimes and peccadilloes of sexuality were weaponised.

This was an era in which a Howard Hughes exhibited limitless power, employing teams of men tasked with both procuring him women and then dispatching with them through payout or intimidation. On the opposite side, the studios had private detectives trailing their own actresses (Anger; Austin; Bartlett and Steele). Certainly, the fawning descriptions of Harvey Weinstein in his heyday, as a neo-mogul, should have taken note that he operated in this same old-school way, what with his private army of former Mossad agents spying on and intimidating women for decades (Farrow).

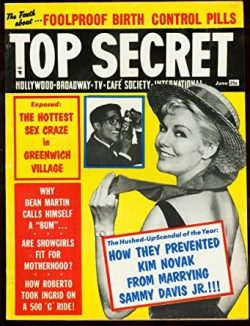

Returning to the 1950s, a series of events involving Harry Cohn, Kim Novak, and Sammy Davis Jr. illustrates the late studio confluence of scandal, sexism, racism, and authoritarian-capitalism, as it flailed and morphed into something new. These events showcase actress rebellion, both professionally and personally—the kind this series has sought to excavate from Hollywood history. Novak was one of countless starlets, considered “on-camera chattel,” who Cohn had tried to threaten and insult into control for decades (Longworth). Cohn’s failures to seduce Novak and his advancing age stand as a metaphor for the waning power of the old ways trying to hang on in the 1950s.

Novak had been a thorn in Cohn’s side and a target of his abuse since her arrival in Hollywood as a working-class girl from Chicago. He tried to change her name, which she had refused. He capped her teeth, bleached her hair, and mocked her “battles” with weight, referring to her as “that fat Polack.” Still, Novack showed quite a lot of courage when in 1957 she refused to show up on the set of Hitchcock’s Vertigo until Cohn had renegotiated her contract, a move no actress would have dared ten years earlier (Longworth).

A pattern ensued of Novak refusing to conform to studio norms, up to and including a clandestine and highly explosive interracial romance with Sammy Davis Jr. Novak was known for saying “the studio doesn’t own me” regarding her secret dates with Davis. While many actresses had battled studio intrusion into their personal lives, Novak was one of the most blatant and most defiant, risking interracial scandal in the conservative era.

In a perfect case of Hollywood misogyny and white supremacy colliding, when Cohn found out that Novak and Davis were dating he hired gangsters to intimidate them and put a stop to it. When this did not work, he paid a black chorus girl $25,000 to marry Davis for one year, and intimidated Davis into agreeing. Nevertheless, the scandal of the interracial romance did make it into the press, and the beleaguered Harry Cohn died of a heart attack the following day (Ibid.). This story cast the emergence of paparazzi against the weakening influence of studio executives. Still, this passing of the baton did little to curb the cruelty, greed, hypocrisy, and racism that had long dominated Hollywood.

We now turn to the actress most synonymous with the 1950s and world-wide celebrity, Marilyn Monroe. Thousands of books and articles have, of course, been written about Monroe. The next article will contribute to this, focusing on the psychological trauma leading up to Monroe’s 1960s death, as well as her meaning to Second Wave feminists.

But even timelier to the #MeToo and Time’s Up moment is the Monroe of working-class and feminist origins, who grew up as a Depression-era, Los Angeles orphan child. Re-situating Monroe through this lens offers a fascinating amount of wisdom. Monroe, in her own words, was a savvy and self-aware economic and cultural actor, with scathing critiques of Hollywood to boot. We can only speculate how Monroe might have contributed, had she lived into her nineties, to the sexual reckoning of the #MeToo moment. But we can be certain that she would have wholeheartedly supported the labor aspirations of Time’s Up, as her interviews of decades ago reveal.

Considering Monroe’s staggering global fame and the current value of her estate, which continues to garner hundreds of millions of dollars in licensing fees, people would be shocked at Monroe’s financial situation in life. Just as Ava Gardner was living as a contracted Hollywood starlet in a rented apartment on “fifty bucks a week,” Monroe never made more than $1,500 a week even at the peak of her stardom (Jordan 16). She always remained a contract player. At the time of her death, Monroe’s estate was worth $100,000, a paltry sum considering the hundreds of millions her films had made the studios (Steinem 3).

Monroe recognized how her hyper-glamorized image allowed others not to take her seriously: “If I say I want to grow as an actress, they look at my figure. Somehow they don’t expect me to be serious about my work” (Monroe qtd in Rollyson 142). Aware of her exploitation, Monroe did start her own production company later in her career (Steinem 81). In fact, Monroe valued working hard. She prided herself on being excellent at keeping house, and had won awards at the fuselage factory where she was employed during the war. As Gloria Steinem notes in Marilyn: Norma Jeane (1988), her excellent and unique feminist reckoning with Monroe, “The Depression idea that a job was a coveted opportunity, a gift, not a right, was a good preparation for Hollywood” (Steinem 90).

Monroe valued hard work and craft, but where she is really overdue to be revisited as a class-conscious activist of Hollywood’s treatment of women is, not surprisingly, in the sexual realm. Monroe had a great deal to say regarding everything from the blurring of sex work and film work to the casting couch, having experienced all of these things. Her positions on sex and labor in Hollywood were also informed by a certain working-class pride.

A class-conscious attitude pervaded Monroe’s life and, indeed, shaped her identity as a woman. She wore only a handful of dresses to auditions and lived on peanut butter when necessary. She slept in her car, and took questionable jobs when she could have easily become an executive’s mistress instead. In fact, Monroe did not even believe in marriage for any reason but love, noting that it “wouldn’t be fair” (Ibid. 87).

Monroe greatly resented the men in Hollywood who thought it was their right to buy, sell, and sleep with women. Certainly, she felt casual prostitution was more respectable than being kept or bought by rich Hollywood men. Speaking of one of the men who molested her as a girl, Monroe said, “Maybe it was the nickel Mr. Kimmel once gave me… but men who tried to buy me with money made me sick. There were plenty of them. The mere fact that I turned down offers ran my price up” (Ibid. 85).

Steinem hones in on a remarkable truth about this “ultimate sex symbol,” exposing complex, perhaps ironic, binds between sex and work: “Marilyn supplied sex so that she would be allowed to work, but not so that she wouldn’t have to work” (Ibid. 90). Monroe’s own words echo Steinem’s claims; she said once in an interview, “If there was only one thing in my life that I was to be proud of, it’s that I’ve never been a kept woman” (Ibid. 50).

Monroe’s more famous quips have become adages: “Hollywood’s a place where they’ll pay you a thousand dollars for kiss, and fifty cents for your soul” (Monroe qtd. In Taylor). But Monroe was sincere, often directly calling out the practices of abusive and exploitative men. Noting the desperate situation of young women, clinging to the lowest rungs of the business while men used and assaulted them, Monroe said, “Hollywood can be a cruel place. Some of those men that take advantage of a starving and lonely girl trying to make the grade as an actress should be shot” (Steinem 50).

Monroe was quite shockingly open about the realities of the casting couch and her own participation in it. In an interview two years before she died, Monroe told writer Jaik Rosenstein that sex had been part of her first work assignments: “When I started modeling, it was like part of the job,” she explained. “All the girls did… and if you didn’t go along, there were twenty-five girls who would…. I’ve slept with producers. I’d be a liar if I said I didn’t…” (Ibid. 89). Monroe’s candor about the casting couch appeared elsewhere: “You can’t sleep your way into being a star….It takes much, much more. But it helps. A lot of actresses get their first chance that way. Most of the men are such horrors…!” (Ibid.).

Even though stardom and success meant escaping the financial and sexual exploitation of many struggling young woman in Hollywood, gaining fame and prosperity left Monroe adrift. It estranged her from working-class people but did not always make her welcome among higher sets. She was “an outsider among the well-to-do, where her lack of education and social skills made her feel personally out of place” (Ibid. 82).

Monroe articulated a lifelong identification with the working class in later interviews, that were often filled with pathos. As Steinem details: “Even as a penniless starlet, invited as decoration to Hollywood parties where men risked thousands on a casual card game, she didn’t want to become one of the rich. ‘When I saw them hand hundred and even thousand dollar bills to each other,’ she wrote, ‘I felt something bitter in my heart. I remembered how much twenty-five cents and even nickels meant to the people I had known, how happy ten dollars would have made them, how a hundred dollars would have changed their whole lives… I remembered all the sounds and smells of poverty, the fright in people’s eyes when they lost jobs’” (Ibid. 82).

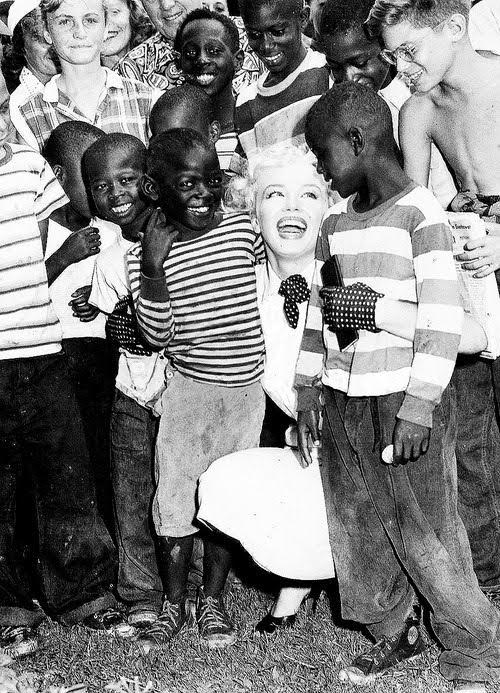

This pride of and in the poor, and lifelong identification with them, meant that she preferred to play to her working-class fans. Some scholars have written about Monroe’s deep commitment to civil rights and her connection with people of color, in this respect. Steinem writes, “She considered herself one of them, and they seemed to sense that (Ibid. 84).

Referencing “the hard way I’d lived,” Monroe displayed both strong class consciousness and a drive for social justice. Few would be aware that Monroe openly praised socialist positions and spoke of communism as “for the people” (Ibid. 94). In one of her final interviews, she passionately argued for civil rights and an egalitarian future in a most Time’s Up fashion: “What I really want to say…that what the world needs is a real feeling of kinship. Everybody: stars, laborers, Negroes, Jews, Arabs. We are all brothers” (Ibid. 32).

Demarcating the 1950s with another landmark case in which an actress took a bold stands leads back to the abuses of the ascendant tabloid press. The 1957 case of Maureen O’Hara versus Confidential reminds that when an actress brought a court case, she was not only going up against major corporate forces, but opening her personal life to scrutiny and scandal. A second case involving O’Hara and Confidential, brought the following year, offers an intriguing, forgotten example of women’s solidarity across racial lines that anticipated this year’s Time’s Up manifesto.

Confidential had become more reckless and libelous, printing more lies and rumors as well as plunging into dangerous new territory in gossip outside social norms like the outing of queer actors and actresses. Much of the Hollywood community felt terrified and terrorized by the magazine but would take no action, as to respond to them or sue them would introduce their charges into the public forum.

O’Hara, in contrast, was utterly outraged by a made up story that she had engaged in sexual behavior in the balcony of Grauman’s Chinese Theatre. In her winning case, O’Hara demonstrated with her passport and filming schedule that she was not even in the United States at the time (Canote; O’Hara).

Around the same time, a class action suit of criminal libel began against the magazine. So many actors were originally involved that it was initially dubbed “The Trial of A Hundred Stars”; eventually all dropped out in fear except for black star Dorothy Dandridge and O’Hara. Two hundred stars begged off or went on vacation, panicked over revelations about their personal lives. Dandridge and O’Hara were among the only to testify, notably both women with much to lose in terms of scandal (Gabler). In the #metoo climate, Dandridge and O’Hara’s united and brave front deserves attention.

The larger libel trial and, especially, O’Hara’s case brought about the downfall of Confidential. The suit ended in a mistrial, but soon after the publisher of the magazine backed down and agreed to stop many of his previous tactics. O’Hara recognized the significance of the case, writing in her 2004 memoir, “Confidential magazine was found guilty of conspiring to publish obscenity and libel. My victory was the first time a movie star had won against an industry tabloid.” She called the case “one of the most important and publicized scandals in Hollywood history” (O’Hara 204). Even if few people are aware of the case now, its ramifications, like those of Olivia de Havilland’s 1943 contract and suspensions lawsuit, were massive (Stipanowich).

The next article will be the series final. It will explore what the breakup of the studio system in the 1960s meant for women. The era’s greatest global superstar, Elizabeth Taylor, was able to negotiate new levels of money, power, and autonomy in the crumbling system. We will examine how her personal scandals both fed the publicity machine and hurt weakened studios at the same time. Finally, we will look at how the Hollywood of the “Swinging ‘60s”, dominated by the likes of Hugh Hefner and Bill Cosby, in fact proffered a phony sexual revolution that merely utilized changing mores to abuse women in new and insidious ways.

References

Anger, Kenneth. Hollywood Babylon. München: Rogner & Bernhard, 1985.

— Kenneth Anger’s Hollywood Babylon II. New York: Dutton, 1984.

Austin, John. Hollywood’s Babylon Women. New York: S.P.I., 1994.

Bartlett, Donald and James B. Steele. Empire: The Life, Legend, and Madness of Howard Hughes. New York: Norton, 1981.

Becker, Christine. “The Production of New Careers: Hollywood Film Actors Move to Television.” It’s The Pictures That Got Small: Hollywood Film Stars on 1950s Television. Christine Becker. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan UP, 2008.

Canote, Terrence Towles. “Naming Names: The Rise and Fall of Confidential Magazine, Part Two”. Web blog Post. A Shroud of Thoughts. 2600 Degrees, August 20, 2012. Web July 14, 2018.

de Beauvoir, Simone, Constance Borde, and Sheila Malovany-Chevallier. The Second Sex.New York: Vintage, 2011.

Farrow, Ronan. “Harvey Weinstein’s Army of Spies.” New Yorker. November 6, 2017.

Gabler, Neal. “Confidential’s Reign of Terror”. Vanity Fair. April 1, 2003.

Jordan, Mearene. Living with Miss G. Smithfield, NC, USA: Ava Gardner Museum, 2012.

O’Hara, Maureen, and John Nicoletti. ‘Tis Herself: An Autobiography. Simon and Schuster, 2005.

Petersen, Anne Helen. Scandals of Classic Hollywood: Sex, Deviance, and Drama from the Golden Age of American Cinema. 2014. New York: Penguin, 2014. Print.

Powdermaker, Hortense. Hollywood, the Dream Factory: An Anthropologist Looks at the Movie- Makers. Eastford, CT: Martino Fine Books, 2013.

Rollyson, Carl E. Marilyn Monroe: A Life of the Actress. Ann Arbor, MI: UMI Research Press, 1986.

Steinem, Gloria, and George Barris. Marilyn: Norma Jeane. New York, NY: New American Library, 1988.

Taylor, Roger. Marilyn Monroe: In Her Own Words. New York: Delilah, 1983.

Wolf, Naomi. The Beauty Myth: How Images of Beauty Are Used against Women. New York: W. Morrow, 1991.

Regions: Hollywood, Los Angles