“What Would Happen If ‘The Goods’ Got Together?”

Thinking #MeToo and Time’s Up Through a Century of Hollywood History

Kerry McElroy writes the series conclusion of Bette, Marilyn, and #MeToo: What Studio-Era Actresses Can Teach Us About Economics and Rebellion, Post-Weinstein.

This series has chronicled a century of Hollywood history, focusing on actresses who’ve navigated oppressive labor and sexual norms. Spanning eleven decades, the series revealed unexpected openings and also missed opportunities. Time and time again, women seemed poised to move ahead in American film, only to be curtailed by an industry that remained stubbornly misogynistic and objectifying.

We’ve looked at Naomi Wolf’s Beauty Myth and her central concept of the Iron Maiden— the way powerful beauty standards work as roadblocks to female resistance (Wolf 17). Nowhere was this strategy more effective than in the Dream Factory, which weaponized glamour in new ways.

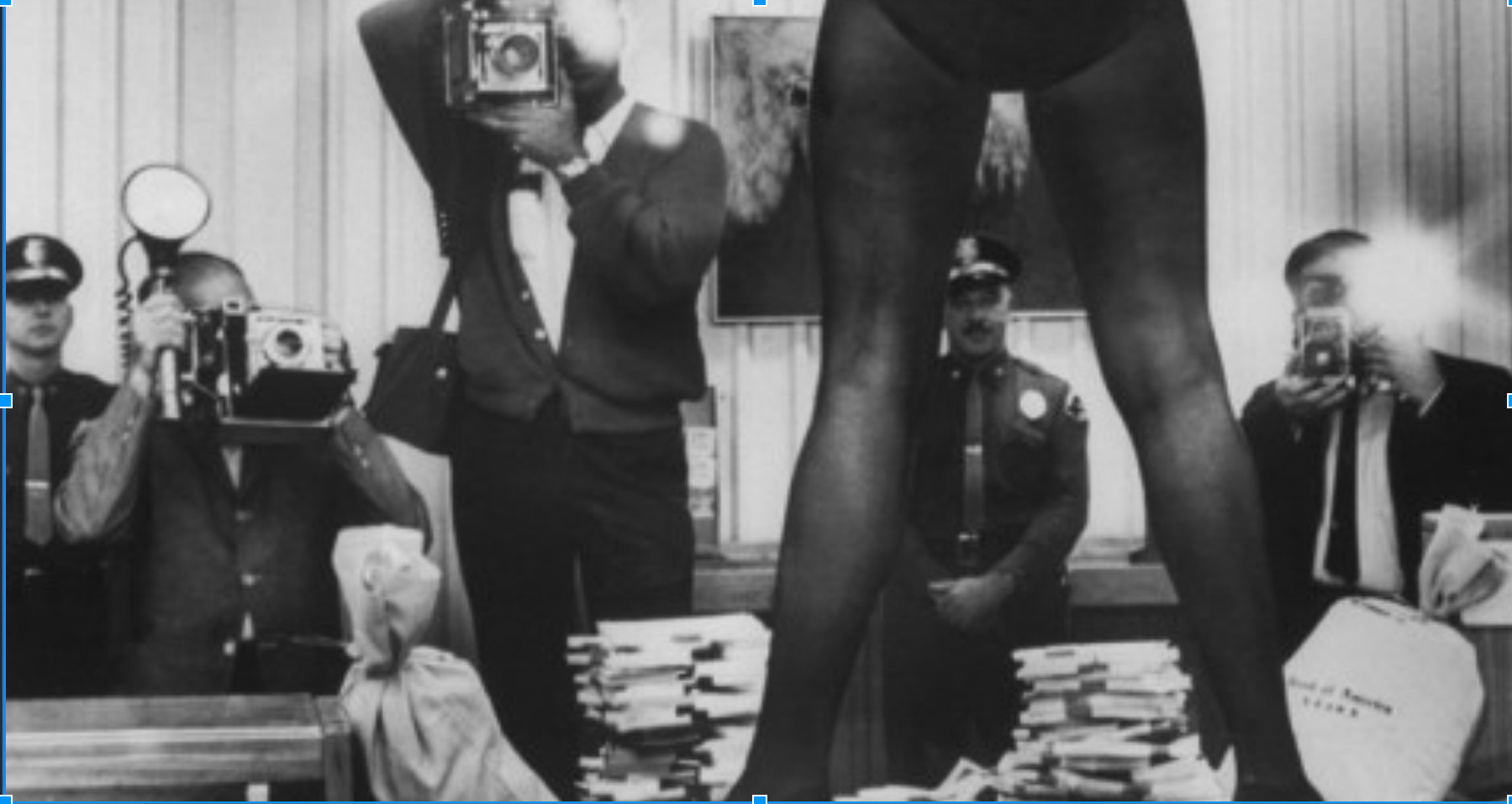

This series took as its starting position the fact that something unique (and uniquely seductive, dangerous, and toxic) has been going in Hollywood, Los Angeles since the 1910s. Hence it has been unapologetic about its Americanist lens. Moreover, the series has relied on American economists to analyze one of the most iconic industries of the century. Peter Drucker, as example, helps to get at the heart of Hollywood’s capitalist misogyny. In his 1980s history, The Concept of the Corporation, Drucker notes that the corporate culture of the studio system was as racist and white male oriented as any of the other American corporate industries. But the film industry was of course particularly misogynist compared to “ordinary” American businesses, because it traded in the buying and selling of women’s bodies and sex. In the high studio era, the ownership of women by the studios amounted to a state of indentured servitude, making this business something new and dangerous altogether (Drucker 28).

Another major thread of the series has been how the recorded histories and the historical winners of Hollywood silenced women’s voices. The impulse to minimize what has gone on in Hollywood for a century between women and men is written into its male-dominated history. This “abuse by film history” included the ways in which truly traumatizing events have perpetually been written off as fun and sexy scandal or gossip, or buried in glamour and nostalgia.

Amber Tamblyn is a contemporary voice worth calling attention to as we conclude the series. This actress-turned-activist offers the kind of institutional critique “from the inside” that we’ve traced throughout Hollywood history. Tamblyn is one of the most eloquent voices of #MeToo movement, and her creative work helped anticipate the sea change of 2017. Tamblyn’s perspective is unique: a Los Angeles native from a studio-era Hollywood family, Tamblyn worked as a teen star before turning a critical eye upon the system. In 2013’s Dark Sparkler, a multimedia book of poetry, art, and essay, Tamblyn ruminates on the tragic lives of Hollywood actresses historical and contemporary, including professional, sexual, and financial exploitations. Tamblyn writes of her own experience as child of Hollywood and its accompanying financial realities:

“I took a break from writing about the dead…to walk around my childhood neighborhood. Everything’s for rent. Or for sale, for ten times the amount it’s worth…My childhood neighborhood is a shrine to my success, and I’m a car with a bomb inside, ready to pull up in front of it and stop pretending” (Tamblyn qtd Branch).

At the forefront of #MeToo, Tamblyn has been adamant about giving voice to a century of women who, in certain ways, lost their own. She shares with this series the conviction that to understand this moment—and its long overdue feminist reckoning—we need to analyze the institutional history of American film, focusing particularly on the experiences and voices of women.

Finally, a goal of this series has been to highlight not only exploitation and abuse of women in Hollywood but instances of courage and candor—women resisting the system. Examples include women who brought contract disputes or individual legal cases. Moreover, in class action suits and “whisper networks,” we have seen forms of solidarity that took shape and helped women survive predatory climates.

Still, these historical examples of resistance give us warning. There are no guarantees that any gains made last year in the #MeToo and Time’s Up movements will remain. Hollywood doubles down, as this series has shown, in response to threats to its power structure. The industry wants nothing more than scandals, like those surrounding Harvey Weinstein, to be neatly swept under the carpet without analysis of the structural economics and sexism that have allowed such behavior to flourish for one hundred years.

To help explore some of this, the series turned to French philosopher Luce Irigraray, and her vocabulary for understanding women’s bodies in the marketplace: use-value, exchange-value, and exploitation. As we’ve seen, Irigraray’s work bears upon the function of actresses in the film economy. Irigaray keenly delineates how “the use, consumption, and circulation of their sexualized bodies underwrite the organization and the reproduction of the social order, in which they have never taken part as ‘subjects’” (Irigaray 84). Many of Irigaray’s questions anticipate and also challenge our current moment: “What would happen if ‘the goods got together’ and revealed the unanticipated agency of an alternative sexual economy?” (Irigaray qtd in Butler 41).

Bill Cosby’s conviction, the exposure of Weinstein, the growth of online survivor networks, and the strength of the Time’s Up manifesto are evidence that the “goods” are finally “getting together”—to demand pay equity and an end to sexual assault. What Irigraray was calling for in 1987 almost seems a reality. The question is whether we are truly witnessing the end of female exploitation and male profiteering in the industry.

With the events of the last year, it feels in some ways as if the American film industry is finally catching up to gains made by women in most other workplaces decades ago. A challenge moving forward, one acknowledged in the Time’s Up manifesto, is to remain intersectional. The strength of the movement rests in its ability to forge solidarity between A-list stars and lesser known actresses, between white women and women of color, and between women who work above the line as performers and women who work below the line in countless middle-class roles. The sea change #MeToo and Time’s Up seeks is one that must affect everyone in the industry: directors, producers, actors, makeup artists, assistants, on-set laborers.

We need to remain vigilant, keep political pressure elevated, and never neglect historicization. This has been the purpose behind this series. The industry establishment will look to gloss over the movement’s pointed critiques with platitudes. They will try hard to make cases like Weinstein’s seem unique—a matter of personal failing, not untenable and systemic injustice. The goal now is to be strengthened by the events, the voices, the courage, the solidarity of the past year; to “use it,” as Michael Moore has said, “to create a world without Harveys.” Or, as Lupita Nyong’o so powerfully put it in her October 2017 op-ed, courageously released in the first month of #MeToo:

“I hope we are in a pivotal moment where a sisterhood—and brotherhood of allies — is being formed in our industry….Though we may have endured powerlessness at the hands of Harvey Weinstein, by speaking up, speaking out and speaking together, we regain [our] power. And we hopefully ensure that this kind of rampant predatory behavior as an accepted feature of our industry dies here and now. Now that we are speaking, let us never shut up about this kind of thing….I speak up to contribute to the end of the conspiracy of silence” (Nyong’o New York Times).

References

Branch, Kate. “Amber Tamblyn Goes Dark: The Actress Opens Up About Her Poetry, Hollywood, and Lindsay Lohan.” Glamour. n.pag. April 10, 2015.

Butler, Judith. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. New York: Routledge, 1990.

Drucker, Peter F. Concept of the Corporation. New York; Signet, 1983.

Galo, Sarah. “Amber Tamblyn’s Dark Sparkler: An Unsettling Meditation on Early Fame.” The Guardian. 8 April, 2015. n. pag.

Irigaray, Luce. The Sex Which Is Not One. Ithaca, NY: Cornell UP, 1985.

Nyong’o, Lupita. “Lupita Nyong’o: Speaking Out About Harvey Weinstein.” New York Times. October 29, 2017.

Olsen, Mark. “Michael Moore Proposes A Plan For ‘A World Without Harveys’.” Los Angeles Times. October 13, 2017.

Tamblyn, Amber. Dark Sparkler. New York: Harper Collins, 2015.

Wolf, Naomi. The Beauty Myth: How Images of Beauty Are Used against Women. New York: W. Morrow, 1991.

Regions: Los Angeles