NYFF Critic’s Choice – “Of Gods and Men”

The Independent’s senior film critic Kurt Brokaw offers his picks from the 2010 New York Film Festival, which runs September 24th through October 10th. For a complete list of his selections, click here.

Of Gods and Men

(Xavier Beauvois. 2010. France. 120 min.)

On rare occasions the essence of a movie is transmitted by a song or piece of music that reinforces the visual content in exactly the right way. When this happens, the moment can be sublime, even transcendent. It happened once in last year’s 47th New York Film Festival during Joao Pedro Rodrigues’s To Die Like A Man. The setting was a silent primeval forest, bathed in red. Tonia, the dying transsexual drag queen, is resting with his young lover, Rosario, and they’re joined by the transsexual Maria and her partner, Paula. The soundtrack quietly eases into the delicate, keening ballad, “Calvary,” executed in a trembling falsetto by the veteran transsexual performing artist, Baby Dee.

The song is about Jesus urging us to weep for our children, not him, to take up the cross and follow him to Calvary. “Who are all the children, who ought to be home in bed?” sings Baby Dee. The cast sits, frozen in their red tint. “What happened to your big sister…wake up, wake up in sorrow, wake up in Calvary.” The New York Times critic Manohla Dargis termed the song and scene “a moment of rapture.”

A very different but equally affecting scene occurs in this year’s festival showing of Xavier Beauvois’s touching and ultimately heartbreaking drama, Of Gods and Men. The setting is a monastery in the mountains of North Africa in 1996, in which the eight French Christian monks in residence are gathered for their evening meal. Most of their food and medical supplies have been carried off by bands of radical Islamic fundamentalists. Groupe Islamiste Armee (GIA) has warned all foreigners out of Africa. The monks have also been told by the Algerian government that they can’t and won’t be protected. Yet all eight have voted to stay. This will be their last supper together.

After the group receives Communion and shares a modest meal, their leader (the excellent Lambert Wilson) plays a recording of Tchaikovsky’s “Swan Lake.” It’s a long scene without a word of dialogue, just the symphony building its stately, swirling movements as the camera slowly examines the faces of the resolute and marked men, all of whom we’ve come to know and like, and some of whom are openly weeping. It is a scene that will break many viewers. “Swan Lake” is surely an unexpected choice as the music to accompany a scene that parallels Christ’s last supper with his disciples, but it works at a deep, deep level. It’s exactly right.

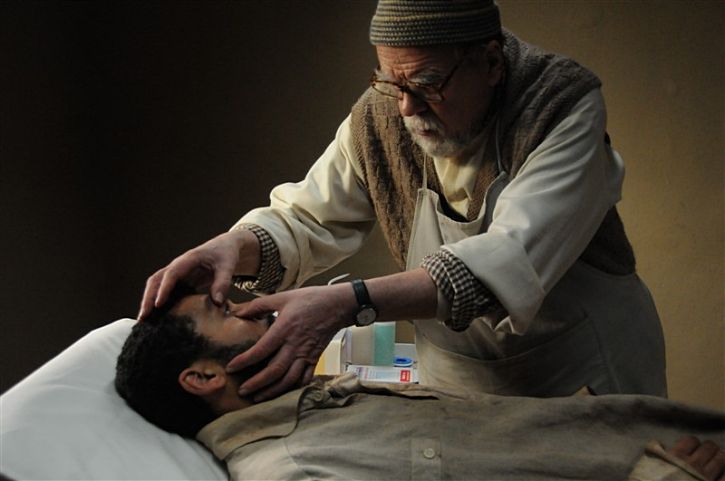

Beauvois’s film has strong resonance today, as similar clusters of monks continue residence in many of the world’s most turbulent and dangerous regions. The Cistercian Order of Strict Observance has 2,600 monks and nearly 2,000 nuns in monasteries and convents worldwide. Their essential mission is to farm and share their food with their neighbors, regardless of anyone’s political intent. One of the monks in Of Gods and Men is the only doctor in the mountain region, seeing some 150 children, women, and men every day.

Most of this inspired and inspiring drama is infused with a firm, confident sense of storytelling, crafted by Beauvois and his co-writer Etienne Comar. The acting is uniformly high and the technical credits are impeccable; it won the Grand Prize at Cannes and is France’s official selection for next year’s Oscars. It has the stature of recent pictures like Katyn and Hunger.

And it has something more: a sense of affirmation and redemption rarely seen in 21st century motion pictures. Consider the religious dramas you may have watched growing up—Pasolini’s The Gospel According to St. Matthew, Zeffirelli’s six-hour Jesus of Nazareth, Rivette’s The Nun, Bergman’s Winter Light, Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc, Pressburger’s Black Narcissus. Many are heavy going, and some posit a punishing or absent God. That is not the stance of Of Gods and Men. The picture has a buoyant sense of goodwill, humor and everyday compassion.

Philip S. Washburn, a distinguished theologian and retired New York minister, tells us that reconciliation between enemies like governments and tribes doesn’t happen easily. Reconciliation is a powerful reversal of hatred, “one of the most difficult of all emotions to encounter. It’s a reversal that arises out of another powerful emotion. It’s a reversal out of love, out of the ‘emotion’ that goes by that name.” The monks understand this implicitly. Washburn says God resides “wherever we let God in. Each breath we draw is connected with the breath of the universe. There is no separation. The burning heart knows we are no longer separated from our source. It knows too we never were.”

Xavier Beauvois has made a film honoring these sentiments.