NYFF Critic’s Choice – “A Dangerous Method”

The Independent’s senior film critic, Kurt Brokaw, is viewing the entire main slate of the 49th New York Film Festival, showing at Lincoln Center September 30-October 16th. Below is one of his critic’s choices—from among 27 feature films plus numerous ‘special event’ features, masterworks, “views from the avant garde” and shorts. His complete list from 2011 is here.

A Dangerous Method

(David Cronenberg. 2011. France/Ireland/UK/Germany/Canada. 99 min.)

A Dangerous Method is this year’s The King’s Speech. Keira Knightley enacts Sabina Spielrein, a suffering Russian teenager in 1904 who finds a “talking cure” through the eminent psychiatrist Carl Jung (Michael Fassbender), just as Colin Firth acted a suffering King George VI who overcame his stutter through intensive talking exercises with the eminent speech therapist, Lionel “Birdie” Logue (Geoffrey Rush). Both pictures are elegantly severe and impeccably produced, but this is the first film by one of cinema’s darkest artists that you needn’t enter with a sense of dread, fearing some awful new mix of Cronenberg shock-and-awe.

The director, now 68, seemed comfortable and assured telling an audience at Lincoln Center that he never looks back on any of his previous work, and his unspoken advice was that we shouldn’t either. This takes some getting used to; you may be reminded of your initial uncertainty when you entered into Scorsese’s The Age of Innocence based on Edith Wharton’s novel, or Truffaut’s The Story of Adele H., a tale of Victor Hugo’s daughter. We’re not accustomed to directors appearing to depart from their known specialties, but Cronenberg makes the leap. He takes his biggest risk in the opening minutes as he unleashes the full fury of 18-year-old Sabina being carried, kicking and screaming, into Jung’s care at Burgholzli hospital in Zurich. She becomes one of his first patients.

There’s no preparation for the kind of mad scene Knightley delivers, and such meltdowns in asylum and prison movies have traditionally been centerpieces or movie climaxes, going back to Olivia de Havilland’s 1948 role in The Snake Pit. Here, barely 30 seconds after the opening credits, Knightley’s giving us everything she’s got. Even her best past performances in films like Atonement and Pride and Prejudice hardly prepare us for such a full-throttle exhibition of (partially) paralyzed rage and hysteria. Viewers may squirm, wondering whether the actress can sustain such extremes of emotion, let alone become the alluring engine driving a heady examination of psychoanalysis-in-the-making.

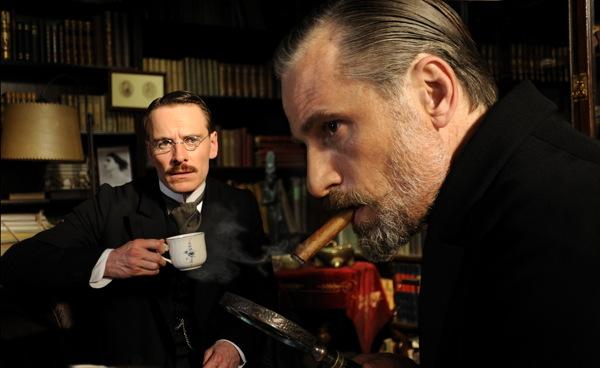

Stay with the virgin Sabina. Watch her negotiate her first steps into what will become a full-fledged adultery and subjugation to the empathetic and suavely handsome Jung. See how she comes to understand the whippings formerly administered by her own father, which she enjoyed and stirred her sexually, and which Jung vigorously repeats. A year later Jung begins corresponding with Sigmund Freud (Viggo Mortenson) and soon they meet, with Freud mentoring Jung. By then Sabina has sorted out her own sexual drive into elements of destruction and transformation. She becomes more of a spurned lover who enrolls in Zurich’s medical school, eventually writing a dissertation on schizophrenia for her degree in psychiatry under Jung’s guidance. Though Sabina wanted a child by Jung and never forgave him for “smashing my whole life,” she shortly marries a physician, has children, and becomes the first female psychoanalyst in the Soviet Union. Jung loses both his mistress and his mentee, though he does his best to convince Freud that Sabina was the one who willingly gave her virginity and plotted their affair, later admitting to Freud that he lied.

Just as Geoffrey Rush helped us understand the pathways around and through stuttering in The King’s Speech, Mortenson, Fassbender, and Knightley give us a fascinating tutorial in psychoanalysis. You can guess which of these two medical treatises may have more appeal to Lincoln Center audiences on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, where every other person seems to be on the couch. Christopher Hampton’s screenplay has a long history, first starting as a movie script for 20th Century Fox, based in part on A Most Dangerous Method, a 1992 history of psychoanalysis by John Kerr. When Hampton’s film script didn’t work out, he adapted it for the London stage as The Talking Cure, with Ralph Fiennes as Jung. Today both Hampton and Cronenberg evidence great pride in the accuracy of their screen version, which draws heavily upon the correspondence of Jung and Freud, as well as Sabine’s diaries and her letters to each.

Once the film takes hold, and it draws you in quickly, Knightley proves she can hold the screen quite convincingly alongside Fassbender and Mortenson. A Dangerous Method is a splendid example of a stage play opened up into a smart, sensitive, and gloriously photographed triumph of moviemaking.