John Cassavetes Talks Comedy, Life, and Reputation in Rare 1989 Interview

A new book offers an intimate collection of interviews with the highly influential director

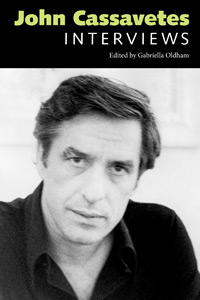

Before there was independent film, there was John Cassavetes. In John Crittenden’s brooding cover photo to Gabriella Oldham’s 24 gathered interviews and solo statements from 1958 to 1985, he’s guarded, challenging, looking half-ready to give the interviewer a piece of his mind at any moment. Cassavetes died in 1989 at 60, having written and directed nine indie features over three decades.

Oldham, a New York-based film historian and scholar who’s building a shelf of seminal texts (First Cut: Conversations with Film Editors; First Cut 2: More Conversations with Film Editors; and Keaton’s Silent Shorts: Beyond the Laughter) identifies the essences of this pioneer: an actor’s director “who felt compelled to let his actors unleash their potentials, shape their own cinematic realities, and play them out naturally on the screen”…a specialist “in men-women relationships and their emotional dysfunctions”…and always an artist “with almost child-like admissions of a belief in humanity’s better self” and “a surprising naiveté he transferred to his characters, both male and female.”

Cassavetes believed in improvisation from tightly written scripts. He worked close-in with a trusted company of both pros (Peter Falk, Ben Gazzara, Seymour Cassel, his wife Gena Rowlands) and amateurs. He crowd-funded pieces of his first feature (Shadows, 1959) on a late-night radio show. He befriended oddball actors like Timothy Carey, who most directors wouldn’t touch. He acted in highly commercial movies (Rosemary’s Baby, The Dirty Dozen) so he could underwrite highly uncommercial movies “about dissolving marriages, love that degenerates into betrayal, the difficulty two people have continuing to communicate well once they live together.” Frank Capra was his idol; he admired the work of Robert Aldrich, Marty Scorsese, Elaine May, Don Siegel, and Shirley Clarke.

In all 24 of the pieces chosen by Oldham, Cassavetes is on point, poised, wary, touchy, and sometimes confrontational. He doesn’t totally trust even the critics who have most applauded his work, and he’s come to accept that his primary audiences may forever be in festivals, museums, and classrooms. Once in a while, Gena Rowlands offers a comment on the six dramas her husband built around her: “With John’s scripts, it’s like being an astronaut on the moon for the first time—the air is very light, you have to wear heavy boots, you have to push yourself out into areas that are very frightening.”

Oldham’s concluding piece is a “lost interview” done in 1985 with the film critic and historian Joe Leydon, first published in MovieMaker (“The Lost Interview: John Cassavetes,” Jan. 29, 2009). Thank you to Mr. Leydon and MovieMaker for permission to reprint. It’s a lion-in-winter summation and Cassavetes is mostly looking back on his prisoner-of-love efforts. But it also perfectly complements a piece of advice Cassavetes gave to aspiring directors as well as actors: “Say what you are. Not what you would like to be, or have to be. Just say what you are. And what you are is good enough.”

— Kurt Brokaw

The Lost Interview: John Cassavetes

Joe Leydon / 1985 (2009)

From MovieMaker, “The Art and Business of Making Movies” (online), January 29, 2009.

Reprinted by permission of Joe Leydon.

Author’s Note: Back in 1985, I wrote the interview—greatly expanded from a piece I originally wrote as film critic for The Houston Post—as a spec freelance article. At the time, unfortunately, no one was buying what I was selling. One editor informed me that Cassavetes was “yesterday’s news,” while another admitted to actively disliking the man’s work. So I consigned the manuscript to my archives, where it remained until I unearthed it, and slightly revised it, as a memorial tribute to mark the twentieth anniversary of John Cassavetes’s death.

Here’s the scene. It is early 1985 and John Cassavetes, somehow both casual and intense sits at a cluttered desk in his office at Burbank Studios, surrounded by blown-up stills from his current effort, Big Trouble. The movie, a comedy now in post-production, is planned as a major summer release by Columbia Pictures. Its stars, many of them in photos surrounding Cassavetes’s desk, include Alan Arkin, Peter Falk, Beverly D’Angelo, Charles Durning, and Robert Stack. Cassavetes is smiling, clearly enjoying himself. The assistants who drift in and out of his office with reports on looping and editing are smiling. And, if you can believe the advanced word dribbling in from studio people who have seen the rushes, Columbia is smiling a great big corporate smile.

What is wrong with this picture?

After all, this is John Cassavetes, the first Angry Young Man of cinema, the gray eminence of American independent moviemakers, a virtual deity to every film school student who dreams of making a splash outside the Hollywood mainstream. Here is the creator of such rough-edged, defiantly unpolished, semi-improvised dramas as A Woman Under the Influence (1974), Opening Night (1977), and Love Streams (1984), pictures in which life is served up like steak tartare: Raw and not appealing to every taste.

This is the maverick director who never walks near a studio backlot, except when he takes an acting job to supplement his meager production budgets. Here is the iconoclast who, along with his wife and frequent star, Gena Rowlands, has gone deeply into debt many times, to the point of mortgaging his West Coast home, to pay for his handmade projects.

Now this same man is wrapping up work on a Hollywood comedy. No kidding.

As he drives to the St. Moritz in Studio City, seeking a break from post-production and a quiet place to talk, Cassavetes grins wolfishly as he considers his atypical assignment as a Hollywood director for hire. “Well,” he begins, dividing his gaze between the windshield and his passenger, “Peter Falk is a real good friend, for one thing. They called me in the middle of the night and said, ‘How would you like to do this? The producer-writer-director [Andrew Bergman] is exhausted. He finds it too much for him to do all these things. It will be kind of fun if you come on for five weeks and have a good time with Peter and everybody.’ And I said yes immediately because I wasn’t doing anything else.

“But as it’s turned out,” the legendary indie adds as he pauses for a traffic light, “This is my seventh month. It’s a lot more difficult than I thought it would be.”

But not as difficult as convincing Columbia you were the man for the job, right? Not really, Cassavetes replies. He has worked in the past with the studio, which released his movies Husbands (1970) and Gloria (1980). Despite all the stories of his epic battles against the Hollywood system, he has more than his fair share of supporters and admirers among the production powers that be.

“Oddly enough,” he says, “I grew up with most of the people who are heads of studios. And while they don’t like my kinds of films, when I make ’em, I really never had too much trouble getting a job in a more commercial area. I just don’t want that, usually.

“But this appealed to me,” he continues. “I thought it’d be fun. I’ve never done a comedy before. In fact, they were a little shaken when I told the actors, ‘Look, I’ve never done comedy before—so let’s cut all the laughs out,’ I said, ‘Laughs are easy to come by. Let’s push the story.’”

Bergman’s original screenplay was sort of a comic take on Double Indemnity, with Alan Arkin as a hard-working insurance salesman drawn into a high-stakes scam by a brassy femme fatale (D’Angelo) and her con man “husband” (Falk). Hoping to collect on a special clause in an accidental death policy, the plotters match wits with a straight-laced, ultraconservative insurance executive played by Eliot Ness himself, Robert Stack.

“So far,” Cassavetes says as the restaurant comes into view, “I think the studio likes the picture a lot, oddly enough. I think they have a lot of respect for me. And I have a lot of respect for them in that they’ve gone along with me. They’re rooting for me to be able to accomplish this.

“I’m not saying it’s not dangerous. It is dangerous because I’m greedy. I don’t want a film that could be my last film—as all films could be—that would be something that could be pigeonholed. I want it to be funny, but I want it to be truly funny. I want it to be something that could happen to somebody.”

Could Big Trouble really be Cassavetes’s swan song as a director? The very idea brings a slight chill to the conversation, causing a frisson that cannot be blamed on a blast of air conditioning as we enter the St. Moritz. Cassavetes remains jocular while we’re at the bar, speaking with mock gravity about the car we left outside with a parking attendant. (“I don’t know if this place really does have valet parking. Maybe that was just some guy who took my keys . . .”) Then he orders a Coca-Cola, instead of the expected pre-lunch cocktail. (This is in deference to the cirrhosis that already has ravaged his liver and bloated his stomach, and will kill him four years hence. –JL)

It’s spooky: From some angles, Cassavetes’s gaunt face evokes memories of the late John Marley, who starred in Faces (1968). Later, after we return to Burbank, he will politely but firmly decline when I ask to take a photo. Even spookier: The sudden intimation of mortality during a pleasant conversation—it’s like something out of one of the director’s movies.

Cassavetes appears both amused and intrigued when I mention my curiosity about a recurring motif in his work: The unexpected, frightening realization that life is short and fragile.

“You mean, how do I look at the death sentence that’s been given all of us? Well, yeah, I think that’s what good drama is made of: Life and death. I mean, if it isn’t life and death, it’s a comedy. Everything passionate, everything to do with love and hate, anything that is important, has to do with someone saying, ‘Hey, this is the last time. This is it, right now, this day that we’re living is the time.’

“I guess I’m colored by the fact that, when you’re making films, me and all the other people working on it work like it’s the last time, the last film, like there is no other film. So I guess the characters become implanted with that, too. In the writing and in the execution. It’s the last time, and we might as well live because we don’t have much of an alternative.

“I think you feel mortality more when you’re most alive, really. Because that’s when you don’t want anything to happen to you. When you’re depressed, let’s face it, you don’t really care about death that much. You think, ‘Listen, that might be a solution to my problems.’ But if you’re having a wonderful time, if you’re feeling life and it’s really grappling with you, then you get worried. It’s like a rich man being afraid of being robbed. A poor man is not so afraid of being robbed—unless, of course, it’s payday. But the day after, you don’t care anymore.”

Cassavetes cares very much about Big Trouble, in large part because it really could be his last film. One moment, he indicates as much. The next moment, however, he contradicts himself: “I could do another movie, easy.” It all depends on his health, he says.

“With this kind of disease, you don’t know whether the liver regenerates or it doesn’t.”

Is it difficult, even after making so many movies about facing up to mortality, for Cassavetes to consider the possibility of his own death?

“Well, emotionally, as I look at it, I’m not aware of anything that’s wrong with me. I guess I can’t cope very well with things that mean a lot to me—like most people. It comes out in different reactions. But I can never face anything that I don’t want to happen. I’ll fight to the death, you know. And I think there have been certain things in the past number of years—well, I wasn’t aware that they were happening, or that they meant that much to me, but they evidently did. They’re personal things; I don’t want to discuss them with myself, why should I talk about them with you?”

Cassavetes is smiling as he speaks, but there is a slight edge to his voice. “That’s fair,” I reply. “I’m conducting an interview, not a psychiatric session.”

“Well you’re doing both,” he retorts, exploding into laughter, vigorously slapping the table where my tape recorder is whirring. “But, seriously, they were personal things. I don’t cope well with the loss of people I love and things like that. I went through a really terrible manic period and I think my health broke down on me. So I’m taking better care of myself. Gena is insisting that the strong body I’ve been given should be cared for a bit more. I don’t know. I guess other people wouldn’t think about it as much, but I rest when I can.”

Faced with his serious ailment, Cassavetes’s reaction is one of annoyance, not fear. “Not having as much energy is very frustrating. I used to have enormous energy and could accomplish a great deal. Now it takes me a longer period of time to accomplish what I could accomplish in a very, very short time. Outside of that—the rest of it—well, that’s life.”

The hard-scrabble days of Cassavetes’s early directing career were long behind him. But he vividly recalls the period in the late 1950s and early ’60s when, still young and optimistic, he tried to revolutionize the art of moviemaking in America. The New York-born son of Greek immigrants, Cassavetes was profoundly influenced by his father, a Harvard-educated businessman who made and lost millions. “My father was a gambler because he had to be,” Cassavetes notes. “From that point of view, I’m very similar. I had to be a gambler—I had no choice. So I’d rather enjoy it, rather than think of it as something terrible or repressive. I’ve been selfish all my life. And the thing Gena says is, ‘What I don’t understand about you is that you’re proud of it!’”

Legend has it that in 1959, Cassavetes actually solicited funds for his first feature, Shadows, on a late-night radio talk show. The legend, Cassavetes admits, is true. At the time, he recalls, he was establishing himself as an actor in live television and sharing his expertise by conducting an acting workshop in Manhattan. After supervising a particularly successful improvisational exercise, he thought of translating the classroom activity into a movie.

“So I went on this show—Jean Shepherd’s Night People—and I said, ‘Wouldn’t it be wonderful if people each sent in a dollar and we’d go out and make a film?’ The next day, seven thousand dollars came in, in dollar bills, and people from all over brought in equipment. It was like a miracle. So then we had to make the film.

“Of course, it cost considerably more than seven thousand dollars, but people continued to send in money. Suddenly there were people calling me up and saying, ‘Well, I’m gonna put in one hundred dollars.’ Hedda Hopper called me up and sent me thirty-five dollars; I thought that was very sweet. But I told her, ‘Fine, I’m taking it. But you don’t get a piece of the profits.’”

Shadows, a highly praised psychological drama, attracted the attention of Hollywood producers. But Cassavetes was less than pleased by the two movies he subsequently made for major studios: Too Late Blues (1961) and A Child Is Waiting (1963). Much closer to his heart is Faces, an ultra-low-budget, 16mm production which took four years to film and edit. (He helped finance the movie with his salaries for acting in The Dirty Dozen, for which he earned an Oscar nomination, and Rosemary’s Baby.) Faces, a drama about the tensions of an upper-middle-class marriage, opened in 1968. Critics and audiences responded with an enthusiasm that took Cassavetes by surprise.

“I was young,” he recalls, “but not that young. We sat around, [producer] Sam Shaw and me, and some of the reviews came in. And they were very important to us, because this was a picture that counted on the press. So we were looking at them. And then we started laughing, ’cause the reviews were so good. I remember one that Roger Ebert happened to write. Sam and I laughed and laughed and laughed and laughed. Sam started pointing at me, I started pointing at the paper and we were laughing. We weren’t laughing at Ebert, but what he said seemed so excessive in praise.”

Not all of Cassavetes’s movies were met with such a reception. “A couple of pictures later,” Cassavetes recalls, “Ebert rapped me. My first thought was, ‘Where’s that first review? Why is he saying I’m such a bad director after this excessive thing? Maybe he’s trying to balance it?’

“I think that all artists, in some strange kind of sick way, pay more attention to the bad reviews. But with me, it’s like I’m somebody who built a car by hand. Somebody takes a ride in a factory-built car and gives that car a good review. Then he rides in our hand-built car that we spent four years on and says, ‘Well, it’s rough, the shift doesn’t work.’ I wanna say, ‘Yeah, but what about the car?’”

Remember: It’s early 1985 and Cassavetes has been polarizing critics and audiences for more than fifteen years. Husbands and A Woman Under the Influence, two brilliant movies that are arguably his best, were very well received. (Cassavetes himself was a Best Director contender for A Woman Under the Influence and Rowlands was Oscar-nominated as Best Actress.) But Minnie and Moskowitz, The Killing of a Chinese Bookie, Opening Night, Gloria, and Love Streams sharply divided critics and failed to attract large audiences.

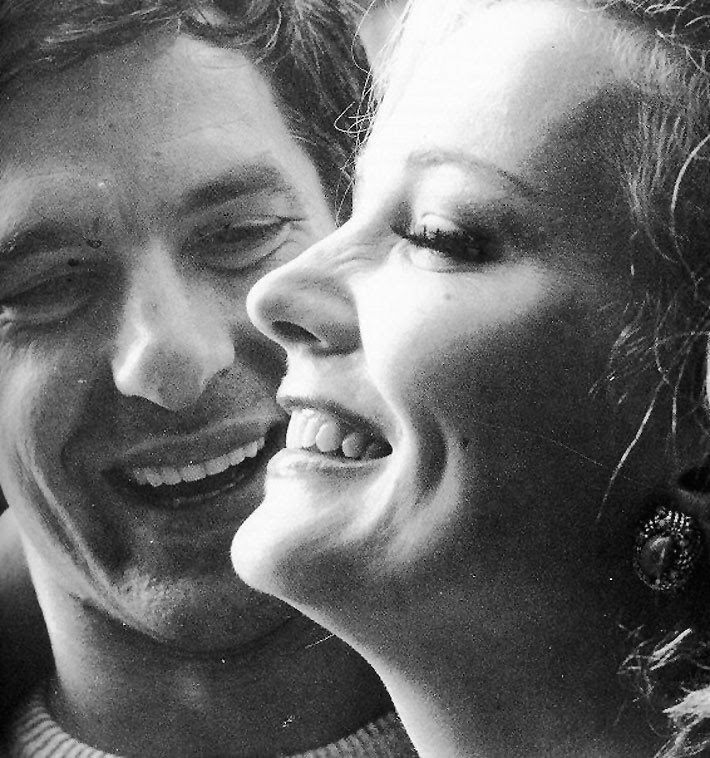

Still, Cassavetes had managed to maintain his drive and enthusiasm—as well as his strong working relationship with his wife of thirty-one years. “Gena’s point of view is totally different from mine,” he laughs. “But I think that’s great. God, if we agreed on everything—can you imagine? Just see us, walking through life, and we’re getting a little older, and people say, ‘Oh, they’re just alike! They agree on everything! If she says ‘blue,’ he says ‘blue.’ They really are together!’

“Well, if Gena says ‘green,’ I say ‘red!’ If I say ‘red,’ she says ‘blue.’ It’s like clockwork! We’re totally, diametrically opposed on everything. I admire the hell out of her, because this has led me into at least an understanding of the way a person with a totally different background, a totally different cultural understanding of life, feels and thinks. The beauty of working with her is that I think she’s a great actress. I think anybody working with her would know it.”

Trouble is, in 1985, some of her best work isn’t easily available for public scrutiny. Minnie and Moskowitz, which was financed by Universal Pictures, occasionally pops up on late-night TV. Gloria, made for Columbia, is available on VHS. But the movies Cassavetes financed on his own are rarely revived—mainly because he seldom permits them to be shown anywhere but museums and film festivals. Our conversation is timed to a retrospective of his work at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

“You know, through the years we financed our own films. And at a certain point, there was a stop put on that by people just not buying them. For any reason. So now, later on, when people come over and say, ‘Oh, we’ll give you a dollar for the film,’ well, I’d really rather show them in museums for people. I’ve already taken a tremendous financial loss.”

So, at fifty-five, is Cassavetes still a maverick?

The question elicits a melancholy smile. Cassavetes stares at his soft drink for a moment as he calmly considers his answer. “People used to love to call me a maverick because I had a big mouth and I’d say, ‘That bum!’ or something like that when I was young. Mainly because I believed it and I didn’t know there was anybody’s pain connected to the business. I was so young, I didn’t feel any pain. I just thought, ‘Why don’t they do some exciting, venturesome things? Why are they just sitting there, doing these dull pictures that have already been done many, many times and calling them exciting? That’s a lie. They’re not exciting. Exciting is an experiment.’

“Now, from the point of view of a guy in his twenties, that was true. But when I look back on it, I think, ‘Yes, that man was a maverick. But . . .’”

His words trail off into weak laughter.

“That reputation keeps with you through the years. Once the press calls you a maverick, it stays in their files. I’ll be dead five years and they’ll still be saying, ‘That maverick son-of-a-bitch, he’s off in Colorado, making a movie.’ As if they really cared.

“You know, in this business, it’s all jealousy. I mean, this is the dumbest business I’ve ever seen in my life. If somebody gets married, they say, ‘It’ll never work.’ If somebody gets divorced, they say, ‘Good. I’ll give you my lawyer.’ If somebody loses a job, everyone will call him—to gloat. They’ll discuss it, they’ll be happy, they’ll have parties. I don’t understand how people who see each other all the time, and are friends, can be so happy about each other’s demise.

“I think people—studio executives and filmmakers—should hate each other openly and save a lot of trouble. It’s like me and actors. I never get along with actors, not on the level of friendship, because I don’t believe in it—only on a creative level. Now, through a period of years, Peter Falk and I have become very good friends, as have Ben Gazzara and I. But only after a period of years. That friendship came out of working on Husbands together and the success that came out of that and a lot of other films, too. Sometimes we’ve been successful and sometimes we’ve been unsuccessful. The creative part of it has always been successful. That’s been the bargain of it, our relationship.

“But I’m sure that the moment I was no longer interested in anything artistic, Peter would not be my friend anymore, and that would be fair game. I probably wouldn’t be his friend, either, if I weren’t interested in art.”

Even so, the opportunity to work with Falk was the primary enticement when Cassavetes was offered Big Trouble. Stepping in at the last minute to direct someone else’s script is usually not his style. But he’s tried it and he likes it.

“I’ve thought about it awhile,” he says, “and I think that’s the best way to come into a picture. You don’t have to hunt locations, you don’t have to go through all the hassles, you don’t have to say, ‘This isn’t right, that isn’t right.’”

Cassavetes pauses and takes another sip of his drink.

“It’s been a lot of trouble,” he says, “but I’ve enjoyed it.”

Making Big Trouble?

“No,” he says, smiling once again. “I meant my whole life.”

Postscript: Big Trouble was spottily released—dumped, really—by Columbia in the spring of 1986. Reviews were mixed, although Vincent Canby of the New York Times, not always a fan of the moviemaker, wrote that it was “great seeing Mr. Cassavetes direct a heedless comedy that appears to be a result of special friendships, rather than (like Husbands) an exhausting analysis of them. He can be a very funny man.”

Cassavetes never directed another feature film. He died on February 3, 1989, at age fifty-nine. His children, son Nick (The Notebook) and daughters Xan (Z Channel: A Magnificent Obsession) and Zoe (Broken English), have all continued their father’s work behind the camera, on many occasions with their mother in a starring role.