New York Jewish Film Festival 2017 – January 11-24

Senior Film Critic Kurt Brokaw picks favorites from the 26th annual fest co-presented by the Jewish Museum and the Film Society of Lincoln Center

Moon in the 12th House

(Dorit Hakim. Israel. 2016. 110 min.)

“Love film? In your 20s and 30s?” asks the splashy new four-color flyer for the Film Society of Lincoln Center’s New Wave program. It’s a $350 (and up) membership obviously aimed at millennials, boasting happy hours and drink specials along with other parties, tickets, talks, preview screenings, and an annual Film Comment subscription.

It’s exactly the kind of positioning and posturing tried by New York’s crown jewel of Jewish culture, the 92nd Street Y, at its ill-fated downtown venue known as 92Y Tribeca. Located at 200 Hudson St. from 2008-13, the facility combined what looked like a sure draw for young Jewish professionals: a 72-seat state-of-the-art movie theater flanked by a giant bar and disco floor. The theater offered trendy indies, femme-centric revivals, previews, and Q&As with stars and directors. It even boasted an original Jewish name, Makor (“source”). But it was a failed experiment, possibly because of its weirdly isolated location near the Holland Tunnel, and perhaps because the notion of packaging a tough, somber take on Tel Aviv millennials like Moon in the 12th House (even if the movie had been made back then) with a night of drinking and partying in lower Manhattan, would have been problematic.

Thus the Film Society’s choice for Opening Night, with its co-presenting partner of 26 years, The Jewish Museum, comes as a real uptown surprise. Will the NYJFF’s traditional blue-hair crowd turn out for this fest’s first searching look at how Israeli authorities seize a booze-and-dope disco den? Will viewers in their 20s and 30s be drawn to writer/director Hakim’s first feature film of the lives of two 20-something sisters, one of whom is the club’s black-leather, astrology-focused co-manager (and the lover of its nasty, cocaine-snorting manager)?

It’s a push toward two disparate audiences, for sure, though Hakim has styled her workmanlike, closely observed drama to appeal to a wide cross-section of viewers. Astrology lovers in particular will be drawn to its title; according to Annie Heese’s Cafe Astrology site, a person in ‘the moon of the 12th house’ “frequently withdraws from contact with the world, and needs a healing, peaceful environment in order to blossom and come out of yourself.”

That description fits Lenny Shoshani (Yaara Petzig), the mopey, near-silent stay-at-home who’s opted to care for her widowed father, paralyzed and mute from a stroke. Lenny drives from their pleasant rural home to a hospital for daily visits and sometimes brings dad home to be in familiar surroundings. She’s a dutiful nurse and caregiver. Her sister refers to her as “a flask—you put water in her, she assumes its shape.”

That astrological 12th house definition also contains another trait that doesn’t define Lenny at all: “You are often flooded with emotions that are hard to define, or completely out of touch with what you are feeling.” That aptly describes Lenny’s older sister, Mira (Yuval Scharf), the black-leathered hostess, gatekeeper and overall poo-bah of The New Limit, Tel Aviv’s most cavernous disco where the sound is at sonic stun and the bathroom stalls are home to every known debauchery. Mira is welded to the gum-chewing short-fuse Doron (Gal Toren), the club owner, who’s coked-to-the-gills and fearful of a police raid at any moment. He’s also unaware he’s gotten Mira pregnant.

Writer/director Hakim is a veteran of Tel Aviv’s vivid night life (she wrote a newspaper column, “Hakim by Night”) which in this film appears some years behind New York’s equally fabled and aggressive downtown club scene of its time (Beatrice, Misshapes, Ruff Club). She wastes no time lining up Moon’s initial story pieces with finesse and dispatch. The core of the film is what happens when Mira, the hot mess, goes from 60 to zero when she throws her cell phone off a bridge, walks away from what local newspapers call “the drug lord of the Tel Aviv scene,” and comes home to her father and Lenny.

Hakim’s debut film, thoughtfully cast and skillfully performed, seeks to fill a delicate cinematic void—what happens to privileged Israeli youngsters growing up in a society of silent or absent parents? It explores Lenny and Mira reaching across generational divides as well as their rural and urban divisions, to reknit their love as sisters.

Will Lenny’s foray into makeup and the club scene (which doesn’t take) draw her to Ben (Gefen Barkai), a sullen 16-year-old skateboarding teen next door who’s housesitting for his traveling mom? Will Mira really give up the persistent Doron and the club life and maybe seek a legit job on a kibbutz? Will the reconciling sisters be there for a declining parent? These are not common questions for an Opening Night NYJFF audience on Manhattan’s Upper West Side.

Hakim gives Mira her own astrological definition of that moon in the 12th house: “It’s people who lock what they look for deep down inside, and think that it will simply disappear. People who bury the kid they were…like me.”

Moon in the 12th House takes a deep breath in launching NYJFF’s second quarter century.

Moon in the 12th House shows Wed., Jan.11 at 3:30 p.m. and 9:00 p.m. in the Walter Reade Theater.

Mr. Bernstein

(Francine Zuckerman. Canada. 2015. 12 min.)

There he is, conducting away, puffing away on the ever-present cigarette stuck in the corner of his mouth. The actor playing Leonard Bernstein in the opening seconds of Mr. Bernstein is Daniel Kash. He doesn’t resemble the preeminent composer and conductor that closely, but he’ll grow on you quickly.

In 1948, Leonard Bernstein gave concerts using concentration camp survivors as musicians in his orchestra. They completed more than 200 performances in the Landsberg, Feidafing and other refugee camps. The image shown here from the JDC Archives doesn’t appear in Francine Zuckerman’s extraordinarily charming time-shifting short, but this review includes it as a helpful reference.

Instead, Zuckerman’s dramatic recreation begins much later, with one of those refugees (acted by Alon Nashman) playing “Rhapsody in Blue” on an LP phonograph. He’s telling his school age daughter, Debbie, how Mr. Bernstein visited his displaced persons camp after World War II and played the George Gershwin piece, and how hearing this enthralling music written by a Jew, conducted by a Jew and played by Jews, gave him hope that one day he might rebuild his own life, even marry and have a daughter. The story obviously makes an impact on the little girl.

Zuckerman spins us forward to 1984. We see the grown Debbie (a picture-perfect Rebecca Liddiard) arriving at a theater in Auckland, New Zealand, where Mr. Bernstein is in rehearsal with the Philharmonia Orchestra. Auckland is where her dad—a local baker—now works. At a break in the rehearsal, Debbie approaches Mr. Bernstein and blurts out that her dad once saw and heard him conduct and play “Rhapsody in Blue” in Landsberg. Mr. Bernstein is floored.

She tells him her father is a baker. Someone else tells him it’s Friday. Bernstein asks if her father is baking challah, and implores her to bring him a loaf, “and also bring your father.” Debbie rushes to dad’s bakery, but her father “has 20,000 loaves to bake by mid-day, and if I don’t bake them, who will? Here, take him as many as you like—tell him hello from me!”

And so she does. And Bernstein understands her father can’t rush out and not bake the challah. And he takes her hand and invites her up on stage and they share a piano bench, in front of a loaf of challah. And then—if your eyes aren’t blurred with so many tears you can’t see it—Bernstein again plays “Rhapsody In Blue” as Zuckerman cuts back and forth between Debbie watching him play, her father in the refugee camp witnessing the performance, and dad somehow hearing it played again as he bakes.

The thank-you credits on this sweetheart of a short start with Nina, Alexander, and Jamie Bernstein, as well they should. You won’t see a more marvelous 12-minute tribute to one of the giants of American music. Production credits are aces, including Deb Filler and Guy Hamling’s ernest and economical screenplay.

Mr. Bernstein shows as part of the Shorts Program Mon., Jan. 16 at 6:00 p.m.

To see the trailer, or to visit the film’s website or Facebook page:

http://www.zfilms.ca

https://www.facebook.com/mrbernsteinthefilm

The Women’s Balcony

(Emil Ben Shimon. Israel. 2016. 96 min.)

Most viewers of Rama Burshtein’s debut feature, Fill the Void (2013), remember her intimate, firsthand knowledge of Tel Aviv’s ultra-Orthodox Haredim community. Burshtein’s film had a shocker opening—the death of a young wife in childbirth at a joyous Purim celebration, leaving a newborn son and grieving father desperate to find a new wife and mother. The bride who fills the void turns out to be the 18-year-old sister of the deceased, who accepts her match-made role out of filial obligation and Psalm 137’s call to Jewish obedience. Fill the Void is never less than serious, and its heart is passionately embedded in tradition.

Emil Ben Shimon’s wise and finely detailed examination of orthodox Judaism in Jerusalem has a similar kind of jolting opening—a communal gathering for a bar mitzvah. Suddenly a portion of the orthodox synagogue’s balcony holding all the congregation’s women and girls gives way, seriously injuring the rabbi’s wife. The dazed worshippers find their rabbi Menashe (Abraham Celektar) traumatized and unable to perform his duties. They must forage for new space in which to worship. Repairs, inspections, permits may take months.

Director Ben Shimon wins our attention and interest faster than Burshtein because his congregation of Sephardic Jews is shown to be more gregarious, resilient, and spirited. For example, Zion (Igal Naor) with his wife Ettie (Evelin Hagoel), the grandparents of the bar mitzvah boy, are quite self-sufficient with Zion running a small retail shop. The women of the congregation quickly return to their normal duties of cooking and finding marriageable partners for their children. (One couple making eyes at each other are Yaffa, the unmarried niece of Ettie, acted by Yafit Asulin, and a handsome seminary student played by Assaf Ben Shimon.) The notion of hiring a psychiatrist to counsel the rabbi is raised but discarded.

One morning a few males are scrambling to put together a minyan of men when the ultra-Orthodox Rabbi David (Aviv Avush) rushes by, offering to join in and then hurrying off. “If he returns, I’m a donkey,” scoffs one fellow. “Turn around, you donkey,” remarks another as Rabbi David rejoins them with the needed extra recruits.

“The best remedy for the soul is Bible study,” states the tall, brisk, and dynamic David, inviting the displaced congregants to worship in his seminary where he teaches and leads services. As you watch him preach to the rafters with a messianic zeal that “women are exempt from scriptures because scriptures dwell within them!,” followed by “all of a man’s blessings come from his wife’s covered hair!” the thought may slide into your mind that David is sounding something like Burt Lancaster revving up his evangelical crusades as Elmer Gantry.

Like Lancaster’s Gantry, David is a rainmaker with a laser focus, cagily offering to supervise and direct the fallen synagogue’s repairs, promising all will be ready by Purim. He also urges his male congregants to offer “kindness, love, and generosity” to their wives by giving them head scarves and making sure they wear them.

The women aren’t buying. “Be a Hasadic rebbi if you want to,” one tells her husband. “I’m a Bible scroll? You should’ve brought me an ark to sit in,” pooh-poohs another. “I’ll save it for Purim,” promises a third, tucking her scarf away. What’s worse, the renovated synagogue reopens with its balcony missing altogether; the females have been exiled to a tiny anteroom.

Ettie and her pal Margalit (Einat Sarouf) promptly get a contractor’s estimate to install a new balcony, but support is hesitant and mixed. Head scarves begin to pop up, and a division between the wives is opened. When the power goes out at Zion and Ettie’s home to which David has been invited for a Passover meal, the ultra-Orthodox rabbi refuses to let the host call a Sabbath gentile to restore the electricity. Everyone sits in the dark trying to find their forks.

At this point, a cadre of women begin soliciting checks to rebuild the women’s balcony, which David forbids. He issues dire warnings about sin and sinning, insisting any contributions be put toward Torah scrolls. “He has the world wrapped around his finger,” laments one woman after David vows to block the construction. The Women’s Balcony has any number of intriguing plot twists and turns up its sleeve as it rolls along to a final scene, a wedding—just like Fill the Void—that outdoes Rama Burshtein’s nuptials in more conventional but also more satisfying ways.

The screenplay of Ben Shimon’s film was written by his ex-wife, Schlomit Nechama. It boasts a punchy, exasperated humor between Orthodox women that’s fresh and disarming. Technical credits for a first feature are very fine, and the ensemble cast matches Rama Burshtein’s in its rich, varied tonalities. The two movies complement each other in cordial and endearing ways, and if Fill the Void enticed you to explore Orthodox culture and practice more deeply, The Women’s Balcony is the one to visit.

The Women’s Balcony shows Sat. Jan.14, at 7:00 p.m.

Past Life

(Avi Nesher. Israel. 2016. 110 min.)

It’s not just the Holocaust and related incidents that swirl through NYJFF decade after decade. All of World War II continues to partly define the Jewish experience, casting its long shadow over this festival. It’s become an essential cinematic glue that binds the core audience. The closest scrutiny is expected, and given without hesitation, to Shoah documentaries and narrative dramas shown here. Watching are 60-and-up real New Yorkers —from retired public school teachers to ‘Red-diaper’ babies, many of them now grandparents— who patiently wait in line at Zabar’s next to Manny Ax for their kosher smoked fish and caviar, and purchase signed Philip Roth novels outside from Enrico the sidewalk book vendor. You don’t pussyfoot around with this audience.

Avi Nesher’s Past Life has a true-life history worth acknowledging before you get your tickets:

Baruch Milch (1907-89) was a gynecologist who witnessed the German invasion of Poland from 1940-43, and saw multiple extremes of Jewish persecution. Raids, house searches, and beatings were common, and while Milch’s position and medical knowledge enabled him to evade the invaders, rotating his family through three rented apartments, he eventually lost his infant son, mother-in-law, and sister-in-law to the Nazis.

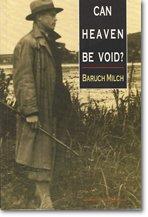

Milch fled to a farmhouse and crawl space with his wife and her sister, then to an underground pit and loft with his brother-in-law. The women were captured and perished; another young child was suffocated when the boy began to cry during the Nazis’ house-to-house searches. Concealed for over a year, Milch filled 61 notebooks—thousands of scraps of paper— with his devastating experiences. Eventually he escaped and became head of a district hospital under the Soviet regime, marrying a local woman, Luisa Geller. They had two daughters and eventually migrated to Haifa in 1948, where Milch refashioned his collected diaries, in Hebrew, into Can Heaven Be Void?, translated into English and published by Yad Vashem in 2003.

Milch fled to a farmhouse and crawl space with his wife and her sister, then to an underground pit and loft with his brother-in-law. The women were captured and perished; another young child was suffocated when the boy began to cry during the Nazis’ house-to-house searches. Concealed for over a year, Milch filled 61 notebooks—thousands of scraps of paper— with his devastating experiences. Eventually he escaped and became head of a district hospital under the Soviet regime, marrying a local woman, Luisa Geller. They had two daughters and eventually migrated to Haifa in 1948, where Milch refashioned his collected diaries, in Hebrew, into Can Heaven Be Void?, translated into English and published by Yad Vashem in 2003.

Writer/director Nesher (whose parents survived the Holocaust) chooses to focus his lushly complex adaptation on the two daughters—Sephi (Joy Rieger) and the slightly older Nana (Nelly Tager)—starting at a West Berlin concert in 1977 at which Sephi is lead voice in an Israeli choir. At the post-recital social, an hysterical older woman, Agniesaka Zielinski (Katarzyna Gniewkowka) steps forward to accuse their father of murder. She’s pulled away by her pale Polish-German choral composer son, Thomas (Jeremy Kotler), who also watched Sephi perform.

Months later in Tel Aviv, Sephi and Nana (a Tel Aviv journalist for a sleazy tabloid) begin separating their traumatic childhood memories from how their father may have wronged this woman so grievously. Nana recalls her father performing abortions and hitting her. Sephi receives a letter of apology (and interest) from the composer Thomas, who’ll be visiting her academy classrooms to lead master classes; he’ll also eventually invite her to sing at a concert in Warsaw. The sisters visit their father’s brother-in-law, who hints of a heinous act by their father during the war involving a child. Nana’s first reaction is that it could make a sensational tabloid story.

The scholarly, grim-faced Baruch Milch (played with grave sincerity by Doron Tavoroy) has hidden his painful past in the diaries. His wife Luisa (a handsomely loyal Eugenya Dodina) is given to nosebleeds whenever tensions ratchet up, as they do with more and more frequency through Past Life. Dr. Milch tells Sephi that during the war he wrote a long diary with tiny pieces of pencil in the basement of a farmer named Zielinski.

He wants her to know his diaries were given to a Jewish committee in Katowice (later forwarded to the Jewish archives in Warsaw for preservation). The father then tells both daughters it was his brother-in-law’s son who cried out and was smothered by the child’s father, though “he accused me of forcing him to do it.” He later shares the critical information that his name in 1944 was not Milch, but…Zielinski.

Nesher has set all the pieces in motion for a robust, sumptuously produced biopic, the kind of inspired-by-true-events movie-movie that’s alive with scary flashbacks, soaring classical motifs, fancy sets with furniture that actually looks lived in, and the upward mobility clashes of a budding virtuoso who aspires to become a composer and a frustrated journalist who’s trying to deal with treating a cancerous tumor. As Sephi and Nana, Ms. Riger and Ms. Tager are far more accomplished professionals (and more convincing actresses) than the millennial sisters moping their way through the astrology-laced Moon.

There are four languages (Hebrew, English, German and Polish) spoken, plus enough plot here for three movies, not to mention a two-handkerchief ending. The real-life and cinematic summaries above only hint at what’s to follow. Revelations pile on revelations. Nesher has world class storytelling and cinematic skills that are at the level of, say, the Italian master blender, Marco Bellocchio, Chile’s Pablo Larrain, and America’s Julie Taymor. Films like Vincere, Neruda and Frida have historical heft in part because serious money up on the big screen pays its own kind of dividends, and Nesher plays well in that league.

Past Life is the latest reminder of how evil empires spread quickly through Europe starting in September 1939. You can draw your own inferences about how that’s happening today infinitely faster through experiential content and social media.

Past Life shows Sun., Jan. 15, at 6:00 p.m. and Mon. Jan. 16, at 3:15 p.m.

This concludes critic’s choices. Watch for Brokaw’s selections from Rendezvous With French Cinema (March 1-12).