Rendez-vous With French Cinema 2017 – March 1-12

Senior Film Critic Kurt Brokaw’s top favorites from Lincoln Center

Nocturama

(Bertrand Bonello, France/Germany/Belgium, 2016, 130 min.)

Dread is the new normal in how we consume media, especially news. In Bertrand Bonello’s darker-than-dark superthriller, we feel the dread more acutely because we’ve watched it unfold too many ways, too many nights, on too many news channels. Here the dread is ratcheted up by a movie maestro who knows how to mix tension and terror into cinematic mayhem rarely seen—or endured—by festival audiences.

But the curators at The Film Society of Lincoln Center and its co-sponsor, UniFrance, recognize our learning curves as viewers and readers have been speeded up by the most advanced print and broadcast news reporting in the free world—available to us in seconds on social, viral, and experiential mobile platforms. We know how successful terror attacks in real life are planned and executed because we’ve read and seen and studied so many. Bonello’s excruciatingly real drama is thus primed to become part of our new normal. It’s not the Opening Night gala on March 1st of this 22nd annual edition of Rendez-vous with French Cinema, probably because galas are still supposed to be—well, gala.

Nocturama’s day-into-night Paris setting seems to have two inspirations you may not have thought of:

Nocturama by day: Nick Cave’s “Babe I’m On Fire.” Cave’s 2003 album with the Bad Seeds, Nocturama, had a 14-minute full-tilt noise jam in which a litany of lost souls (a Buddhist monk, a junkie, a Rastafarian, a libertarian, a right-winger, a compulsive shopper, even Bill Gates, Sonny Liston, Walt Whitman and “the poor Pakistani with his lamb Bhirriani” all share a common destiny. They’re all on fire. Just like Paris is going to be in late afternoon. This song was surely one of Cave’s most inspired 20,000 days on Earth. (Speaking of names, Cave’s 2014 fabulist doc/fantasy, 20,000 Days on Earth, was also a critic’s choice here.)

Nocturama by night: Select zoos have nocturamas in which nocturnal animals can be viewed at night, with interior lighting. Bonello’s terrorists choose a multi-level department store to take refuge in for the night, killing the four-man security staff (Paris’ La Samaritaine stands in, as it has in other movies including Holy Motors and The Bourne Identity) and enjoying a taste of luxe life from Chanel to Issey Misaki while they watch the city’s first responders and frantic officialdom from a bank of wall screens.

So who are these terrorists, some of whom are pictured above overlooking a spectacular night view of Paris? Bonello has cast his film very wisely, staying multi-ethnic and multi-racial. Just read the cast list and consider their probable countries of origin: Finnegan Oldfield, Vincent Rottiers, Hamza Meziani, Manal Issa, Martin Petit-Guyot, Jarnil McCraven, Rabah Nait Oufella, Laure Valentinelli, Ilias Le Dore, Robin Goldbronn, Luis Rego, Hermine Karagheuz.

Nearly all are under 30 and most could pass for what they seem to be: students. Very few are fully developed characters and their motives are left deliberately murky. The one face you may recognize in the movie in Adele Haenel, a familiar presence on the Walter Reade Theater screen (Love At First Fight, Water Lilies, In The Name of My Daughter). She’s not one of the gang but she summarizes the film’s underlying concept to one of the cell members in two succinct sentences: “It had to happen. We knew it would.”

Nearly all are under 30 and most could pass for what they seem to be: students. Very few are fully developed characters and their motives are left deliberately murky. The one face you may recognize in the movie in Adele Haenel, a familiar presence on the Walter Reade Theater screen (Love At First Fight, Water Lilies, In The Name of My Daughter). She’s not one of the gang but she summarizes the film’s underlying concept to one of the cell members in two succinct sentences: “It had to happen. We knew it would.”

It’s that knowing-something-terrible-is-going-to-happen that keeps us glued to the stealth plotting that occupies most of Nocturama’s first hour. The kids are gathering at their assigned locations with specific tasks: planting the semtex plastic explosives in individual cars, the Ministry of Interior, the HSBC Tower complexes, the Joan of Arc statue. The devices are wired and timed to detonate simultaneously. And they do.

Nocturama’s night, inside the department store, isn’t part of the new normal. We’re rarely given a look at how terrorists celebrate their successful missions. This is where Bonello demonstrates some master licks with his focused young cast. Parents are telephoned and overnight excuses are made. One kid propels a motorized go-cart around the empty aisles. An exhausted young woman takes a nap on silk sheets. A guy soaks away the day in a splendid bathtub, sipping cognac. The ’60s pop hit, “My Way,” is memorably mimed. Jewelry and diamonds are grabbed up. The gang invites in an old street beggar and his female companion for the best meal they’ve had in years.

Nocturama deviates here from the kind of youth-on-a-lark kick that informed Grady Hendrix’ recent horror novel, aptly titled Horrorstor, which was set in a Cleveland furniture superstore, staffed by an archetypal millennial cast, working a nine-hour dusk to dawn shift, who’ll be slowly killed off by force or forces unknown. Horrorstor plays by genre rules that we know since Roger Corman. Nocturama invents its own comings and goings, and coming on top of the explosions we’ve witnessed, they’re far more disturbing for being so ordinary.

And then the French National Police anti-gang brigade, silent and swift, moves in.

Bonello is a formidable, blazingly assured and innovative director. He doesn’t quite traffic in the extreme imagery of, say, Lars Van Trier or Yorgos Lanthimos, but in his House of Pleasures a beautiful prostitute has her mouth slashed by a client. Bonello’s most memorable appearance in Lincoln Center was probably Saint Laurent in 2014. Viewers still talk about the scene in which a near-comatose YSL (Gaspard Ulliel) bleeds and crawls across a floor of broken glass, while his cute bulldog writhes and chokes and dies from an overdose of pills. Be careful.

Nocturama shows Saturday, March 4, at 6:15 p.m. and Sunday March 5, at 9 p.m. at the Walter Reade Theater.

The Dancer

(Stephanie Di Giusto, France/Belgium/Czech Republic, 2016, 108 min.)

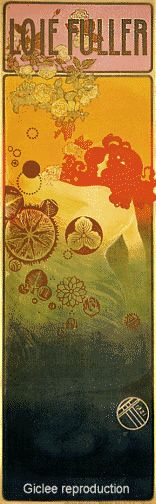

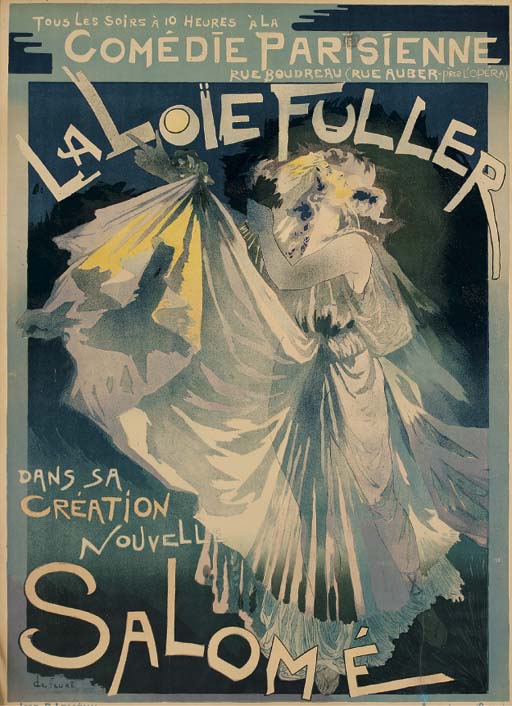

Hanging in the critic’s Manhattan apartment is the poster shown here. It’s a reproduction, purchased decades ago, measuring 7”x23”, an odd size; the frame probably cost more than the print. In its colorful, art nouveau styling, it brightens up an otherwise nondescript hallway. It’s lettered “Theatre de Loie Fuller Exposition Universelle” and until last week, no one in the family nor any visitor in 40 years has ever registered on Loie Fuller.

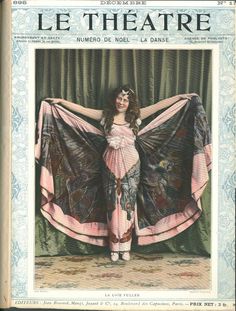

All that has changed with Stephanie Di Giusto’s sumptuous biopic. Fuller (1862-1928) was an artist and inventor of ingenious theatrical wizardry. She’s shown here shyly displaying a flower garland in a tinted turn-of-the-century postcard, but her enduring contribution to dance was transforming the ancient art of skirt dancing into a pinnacle of magical visualization. Today the Dance Heritage Coalition heralds her as an Irreplaceable Dance Treasure.

The full view of Fuller here only begins to hint at the wonders devised by this plain, mousey Illinois girl. Di Giusto imagines her coming-of-age years tied to a blustery loudmouth dad who’s shot dead taking a bath in a hardscrabble outdoor frontier setting. The girl migrates to a Brooklyn tenement, shy, fragile and vulnerable. She tiptoes around lecherous photographers who pose topless girls for peep show stereopticons, and accidentally discovers the seeds of her craft doing a stage play walk-on—when her skirt falls, she picks it up and begins improvising a twirling dervish kind of routine. It’s an act of desperation but the audience believes it’s some kind of specialty number and rewards her with an ovation.

Fuller immediately begins thinking about how to enlarge the effect. She moves to fin de siecle Paris, and would live in Europe throughout her career as America’s first expatriate dancer. Switching to silk, she experiments with phosphorescent lighting and plate-glass cutaways under her feet. luminescent salts and colored gels plus slide projector magic lanterns to cast images onto her costumes. Fuller’s most dramatic innovation takes shape when she sews bamboo rods into her silk sleeves, extending and exaggerating her swirls. And she caps these intriguing staging devices by inviting audiences to conceive of her transforming into a flower, a butterfly, a snake, even an ocean wave. She will become the dance essence of the Art Nouveau movement.

Stephanie Sokolinski, the French singer/songwriter billed as Soko is an inspired choice as Fuller.

Di Giusto shapes her growth from an awkward adolescent into a brittle, hard administrator who works tirelessly to win audiences and recognition, patenting her stage lighting and chemical effects, while opening a school and dance company in 1908. Soko plays her as a woman perpetually engaged in literally breaking glass ceilings; she can be impatient and even caustic, and at certain moments she bears a startling resemblance to the snarly ’50s actress Mercedes McCambridge (All the King’s Men, Johnny Guitar).

Di Giusto also brought on board Jody Sperling, another wise decision, as choreographer, creative consultant, and dance coach to Soko.A New York dancer/choreographer, Sperling runs Time Lapse Dance and is regarded as Fuller’s premier translator, executing her own unique works on locations as far-flung as polar ice caps. Soko is up for the physical demands and split-second timing of the role—she glories in it, and you won’t mistake her for some newcomer in the Cirque du Soleil. The movie has moments that capture what one French poet has called “the dizziness of soul made visible by an artifice.”

The film’s one male interest of note is Count Louis Dorsay, played by Gaspard Ulliel in a role that echoes his title role collapse in Saint Laurent. This time he’s sniffing ether, thinking it may alter his perceived impotence, and providing the funds (which Fuller pilfers) to move to Paris. Dorsay lolls about the scenery, letting her use his estate to house her dance school.

Of more interest is 17-year-old Lily-Rose Depp, cast here as the iconic Isadora Duncan, the wunderkind befriended by Fuller.

Again it’s a calculated decision by director Di Giusto, as the weathered, browbeaten, and device-laden Fuller contrasts well with the long loose hair and delicate feet of the uber-pure Duncan. It’s technology vs. nature, and it’s almost inevitable that the two women will be sexually drawn to each other. (In real life Fuller found lasting happiness with a banking heiress who always dressed in men’s suits.)

Their scenes, like the one shown here, have a production design and use of lighting that you rarely encounter in historical dramas. The style is blown-out illumination that curtains many interiors in a mix of sunlight and shadow, and it may remind you of Ridley Scott’s staging in films like Gladiator, The Duellists, and 1492-Conquest of Paradise. Scott used it in his “1984” MacIntosh television commercial, and Di Giusto, an advertising veteran, may have gleaned it there. The lighting intensifies the staging effects and overall theatricality of Fuller’s art—you’re in a microcosm of the Belle Epoque.

Soko, caught here preening in costume before a battery of Cannes photographers, gives The Dancer both credibility and star value.

With its handsome $9 million budget, Di Giusto’s first film can fairly be saluted as an artistic triumph. It takes a figure lost in the mists of time—adorning the cover of Le Theatre and poster art for Comedie Parisienne—and reinvents her for a whole new audience. You’re now ready to view the theater trailer for The Dancer with informed eyes.

The Dancer will show Thursday, March 2, at 1:45 pm and Monday, March 6, at 9:30 pm.

The Odyssey

(Jerome Salle, France, 2016, 122 min.)

It may be only coincidence, but Jerome Salle’s Closing Night selection and the Closing Night selection of last fall’s New York Film Festival, James Gray’s The Lost City of Z—both curated by the Film Society of Lincoln Center—share an unprecedented list of similarities:

Both movies are biopics of larger-than-life adventurers—surveyor/cartogapher Percival Fawcett, who spent much of his life searching for the fabled lost city of El Dorado, and marine ecologist/oceanographer/film maker Jacques Cousteau, who spent much of his life exploring the Earth’s deepest and most isolated seas.

Both men groomed and eventually lost sons who followed in their fathers’ obsessive pursuits. Both sold family heirlooms to help finance their expensive expeditions. Both married women who remained devoted throughout their lifetimes, despite years of absence (Fawcett’s wife, Nina, played by Sienna Miller) and years of marital straying (Cousteau’s wife, Simone, played by Audrey Tautou).

And both are played by the kind of strong-jawed matinee idols—Fawcett by Charlie Hunnam, Cousteau by Lambert Wilson— that are more reminiscent of 20th century movie heroes like Clark Gable, Charlton Hesto,n and Stewart Granger. Like the penny-a-word creations in 1930s and ’40s Adventure and Argosy pulp magazines, Fawcett and Cousteau are readily identifiable “bent heroes”—flawed but fiercely independent men’s men who inspire loyalty in their crews and longing in sweet young autograph seekers.

What’s more, both films have a strong literary pedigree. The Lost City of Z grows out of Fawcett’s own journals and David Grann’s meticulous tracing of Fawcett’s multiple expeditions. The Odyssey is based on Jean-Michel Cousteau’s 2012 memoir, My Father, the Captain: My Life with Jacques Cousteau, and Albert Falco’s Capitane de la Calypso, adapted for the screen by Satte and Laurent Turner. Jean-Michel is acted by Benjamin Lavernhe, and Cousteau’s first mate, “Bebert” Falco, is played by Vincent Heneive.

Perhaps most importantly, both films are (for the most part) family friendly, a rare and welcome treat at these two closely watched Manhattan festivals. They’re multiplex popcorn movies that don’t feel out of place wrapping up their respective top-of-the-line annual fests, in which much independent product struggles to find a distributor and then an audience.

The Odyssey moves with lightning speed in telegraphing over two decades of Cousteau’s life. In the first hour, Salle’s camera rarely stops moving, and the preparation of a battered, barnacle-covered Royal Navy minesweeper into the mariner’s state-of-the-art research lab is going to thrill James Cameron, today’s successor to Cousteau both as film producer and oceanographer. Salle makes us aware right away that Cousteau’s two sons are confidently growing up in an underwater world because of dad’s 1943 invention (during his Navy duty) of the Self Contained Underwater Breathing Apparatus (SCUBA), the Aqua-Lung.

Shifting from island locations in Croatia to South Africa and the Bahamas, we quickly sense Cousteau’s impatience to seek out and document what’s never been seen. When he makes his son Philippe (Pierre Niney) his co-producer and cinematographer, the younger Cousteau films the first up-close encounters with killer sharks from outside the protective steel cage his crew takes refuge in. Philippe also shoots a languorous visit with the kind of 94-foot whale that’s stretched across the ceiling of New York’s Museum of Natural History, forever intimidating generations of children who walk under it.

These scenes from the ’50s television series The Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau, his 1956 Palme d’Or winner The Silent World (co-produced with Louis Malle), and a follow-up 1977 series, The Cousteau Odyssey, have a lingering visual power even today. The father screens his work to family and friends on 16mm reel-to-reel and on a small television monitor. In Salle’s breathtaking re-creations, aided by discrete computer-generated wizardry and seen on the biggest screen you can find, they have a jaw-dropping splendor that Salle pauses to let you drink in.

Cousteau’s visit to Antarctica, where the Calypso nearly founders in stormy seas, continues underwater filming, here taking on an otherworldly coloration you may have first noticed in Werner Herzog’s Encounters at the End of the World in 2008. Herzog shot around Ernest Shackleton’s original base and diving camp, and Salle’s work refreshes that Saturday matinee brand of movie magic.

The human dynamic here makes a grumpy contrast to all this nature-as-phenomenon. Cousteau is another ’60s Don Draper in ocean fins, and Audrey Tautou’s hair goes gray as she retreats to the bottle and her cabin onboard the Calypso. She guards Jacques in part to keep him from hauling his lovers on board. It’s a grim, thankless role but if nothing else it should forever erase that dewy Amelie grin that’s forever trailed Tautou.

Cousteau’s relation with his favored son is more problematic. Philippe is torn by Simone’s anguish over her husband’s repeated infidelities, and he’s also aware dad is going to always be chasing the budgets ABC-TV is too stingy to provide. There’s a quick but pointed scene in which the son witnesses the ship’s cook dumping a barrel of garbage and plastic containers overboard. At one point he blurts out that he wishes he had a real father, and Cousteau’s tight-lipped reply is that he never should have had children. And then Philippe, an experienced pilot, climbs behind the controls of a sleek two-passenger aircraft in which something goes terribly wrong.

The subsequent events reunite Cousteau with Jean-Michel, the other son, who’d become an architect, and their 14-year commitment together to ecological causes. By this point The Odyssey has about run its course, and Salle relies on a succession of titles to summarize Cousteau’s closure at age 87 in Paris. Cousteau remarried the mother of two of his children, after Simone’s death from cancer in 1991, another secret affair Salle elects to omit. That woman, Francine Triplet Cousteau, is today president of the nonprofit Cousteau Society. …As they say, only in France.

The Odyssey will show Saturday, March 11 at 6 p.m. and Sunday, March 12 at 8 p.m.

150 Milligrams

(Emmanuelle Bercot, France, 2016, 125 min.)

Where have all the female whistle-blowers gone? It’s been 17 years since Julia Roberts made her case against contaminated water in Erin Brockovich. It was even further back in the 20th century when Meryl Streep took on radiation poisoning in Silkwood (1983) and Lindsay Crouse played a valiant nurse in The Verdict (1982).

Whistle-blowing seems to have become a guy thing, from Crowe’s tobacco indictment (The Insider) to Clooney upending the weedkillers (Michael Clayton) to Fiennes tracking a tuberculosis drug that did in his wife (The Constant Gardener). Edward Snowden as Citizenfour has become world cinema’s most outspoken critic of government.

This fest’s most satisfying surprise is a narrative drama that instantly joins its female-led predecessors above. 150 Milligrams is not to be missed, in part because it’s a fearless portrait of a physician, Irene Fanchon, who faces off against Big Pharma—here the French makers of Mediator, a familiar diabetes drug on pharmacy shelves since the 1980s and prescribed to millions of French patients. But starting in 2009, when Bercot’s drama begins, Dr. Fanchon’s university hospital in Brest observes victims of cardiac valve damage and pulmonary hypertension that she believes are linked to Mediator. When one of her eleven patients dies, she takes action.

Fanchon and a medical researcher associate, Antoine Le Bihan (a fine Benoit Magimel) launch a case-control study and gets immediate pushback from the hospital’s administration and the drug company. Her “methodologies are unsound” and “she’s not even a cardiologist.” Fanchon persists, seeking help from a mole within the National Health Insurance Fund organization—much like Hal Holbrook’s ‘Deep Throat’ informer in All the President’s Men— as well as a brassy investigative journalist from Le Figaro.

Dr. Fanchon is pictured holding her book, Mediator 150mg: How Many Dead? Her small publisher, Editions Dialogues, is initially forced to withdraw the book and delete its “How many dead?” subhead. The corporation defends its drug, insisting that only of-the-moment advances in echocardiology might have detected any possible side effects.

But Dr. Fanchon observes “they were withdrawing the drug on the sly.” She makes the analogy of a car manufacturer who corrects a defect in its production line but doesn’t warn people who have the car. What she’s hoping is that a court will acknowledge the state of scientific knowledge as being predictive of the risk of pulmonary hypertension, and that the high incidence of toxic value disorders should never have been ignored. She wants Mediator off the shelf.

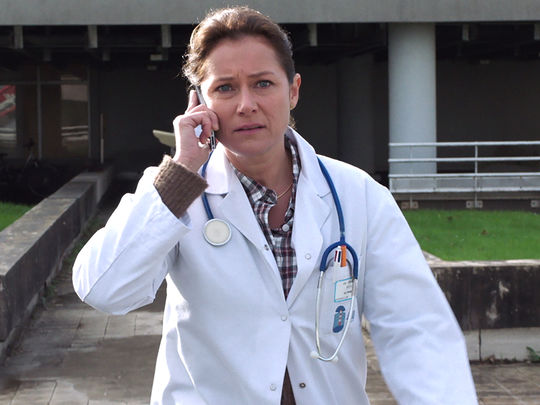

The cinematic news here is that 150 Milligrams is a huge win-win for its indefatigable director, Emmanuelle Bercot. The Bercot whirlwind was last showcased here acting the frazzled lawyer in Maiwenn’s My King (another critic’s choice) and directing the fiery youth dustup, Standing Tall. Her dual win is shared with Bercot’s leading lady and pulmonologist, Sidse Babett Knudsen. She’s a veteran Danish actress whose varied portfolio includes playing Danish Prime Minister Birgitte Nyborg, plus starring in The Duke of Burgundy, the Oscar-nominated After the Wedding, and partnering Tom Hanks in both Inferno and A Hologram for the King.

Knudsen gives 150 Milligrams every ounce of her energy, passion, humanity as well as humility—it’s easily the best performance in this festival. There isn’t a whiff of self-promotion or self-aggrandizement in her actions. At times she talks so fast and volubly she begins to choke, and once while opening a door too fast, she smashes her forehead so hard, she requires stitches.

What she delivers, like Roberts and Streep in their ceiling-breaking tour-de-forces, is enduring, unflagging determination against all odds. This actress has soul. It’s easy to champion her concerns—which are supported by adoring children and a calm husband— but as a medico she has to win your interest, your confidence, your trust, and your patience to wade through two solid years of investigative procedures and dense medical detail.

“I never wanted my calling to become a whistle-blower,” she sighs at one point. “My calling is to care as best I can.” Her outcome is yours to discover.

150 Milligrams shows Saturday, March 4 at 3:15 p.m. and Monday, March 6 at 4:15 p.m.

This concludes critic’s choices.

Watch for Brokaw’s picks in the 46th annual New Directors/New Films fest sponsored by The Film Society of Lincoln Center and The Museum of Modern Art (March 15-26).