So You Want to be a Major Film Artist?

Senior Film Critic Kurt Brokaw Celebrates an Enthralling New Documentary on Master Cinematographer Carlo Di Palma

Water and Sugar: Carlo Di Palma, The Colors of Life; Fariborz Kamikari; 2016; Italy; 90 min.

Anyone who could become a trusted collaborator with directors as startlingly different as Michelangelo Antonioni and Woody Allen deserves close scrutiny. What could you learn from such a person? Which life lessons and work habits might you profit from by close examination of this artist’s career? How many of his bottomless tool kits of cinematic techniques should you absorb, borrow or steal to enlarge your own craft and help build your own artistic vision?

Produced by Di Palma’s widow, Adriana Chiesa, Water and Sugar anchors a ten-film retrospective—all presented in 35mm—by the Film Society of Lincoln Center (7/28 to 8/3) capturing some of the most cinematically diverse accomplishments in a lifetime (1925-2004) spent behind the camera. Kamikari’s 90-minute doc joins the must-see Red Hollywood (1996), Thom Anderson, and Noel Burch’s massive compilation of clips from early Hollywood movies that subtly wove the left-wing philosophies of blacklisted screenwriters and directors into major film genres. Water and Sugar can also stand beside Bernard Tavernier’s My Journey Through French Cinema (2016), the director’s exquisite assembly of his favorite French directors, stars, writers, music composers, and other artisans, also from the first half of the 20th century. Water and Sugar is half the length of each of these two opuses, but it’s just as rich.

So you want to become a major artist like Carlo Di Palma? See if you can apply these highlights of his life to yours:

Start as young as possible and apprentice yourself to the game changers around you.

Di Palma’s mom ran a flower shop in Rome; his dad repaired cameras, and his older brother was an electrician at the Safa Palatino film studios. At age 15, Carlo was hired as a focus operator on Luchino Visconti’s first movie, Obsession, the pre-Hollywood adaptation of James M. Cain’s The Postman Always Rings Twice. It was an indelible introduction to the shadowy, chiaroscuro world of film noir.

The teenager moved from this assignment into Roberto Rossellini’s Paisan and Rome, Open City while attending classes at the city’s film school, a training ground that seeded the roots of post-War Italian neorealism. Di Palma shot documentary footage alongside Swedish master Sven Nyvquist of Allied forces entering a newly free city. Continuing as a focus puller and operator on Visconti’s La Terra Trema and Vittorio De Sica’s Shoeshine and Bicycle Thieves, he evolved a philosophy that “every film has its own creativity, its own way of seeing, of thinking, of giving light to a value.”

Di Palma’s experience lensing It Happened in ’43 (1960) directed by Florestano Vancini, was the first of many concrete innovations. He shot day-for-night in a sinister fog enveloping an outdoor square, whipping up an artistic overlay on to neorealism’s usual gritty canvas. And in Gillo Pontecorvo’s Kapo and Pietro Germi’s Divorce Italian Style, he began a series of eye-popping movie-star closeups (Susan Strasberg and Emmanuelle Riva in Kapo, Marcelo Mastroianni in Divorce) that would become another Di Palma signature. He was evolving into an artistic leader in what’s been called “cinema’s Renaissance workshop.”

Find your mentor and then exceed your mentor.

Antonino’s early DP was Gianni Di Venanzo, who brought grace and fluidity to the esteemed director’s early dramas of alienation and estrangement, like Le Amiche and Il grido plus the better known Le Notte and L’Eclisse. Di Palma studied Venanzo’s technique and wondered how that vision would work in Technicolor. Antonioni gave him the opportunity to see in Red Desert (1964), described by Columbia University professor (and director of the New York Film Festivals for a quarter-century) Richard Pena as “a watershed moment in making color a truly aesthetic element in filmmaking.”

With its industrial landscapes choked with pollution, Red Desert dared to plunk a posh sophisticate (Monica Vitti) into its turgid murkiness. Di Palma sensed right away “she was a woman who feels and transfigures reality in a certain way,” failing to adjust to a transformed society in which even birds learn to avoid the poisonous yellow factory smoke. Antonioni’s drama became a marker in Italian cinema.

The Antonioni/Di Palma duo followed up with an even more ambitious drama two years later, Blow-Up, in which Di Palma used Bausch & Lomb lenses to render artificial landscapes. Antonioni stated he wanted “the hardest and most aggressive of colors.” “So we painted the trees, the grass, the streets, the paths, the houses different colors to tell the story,” remembers Di Palma. Pena summarizes the visual differences between Red Desert and Blow-Up, with the latter film “widening the perspective” and letting the illusory landscapes fill the distances between the characters.

Fall in love with your leading lady and direct her yourself.

Di Palma was drawn to Antonioni’s leading lady and muse, Monica Vitti, with her casual intensity and a hint of raw carnality. After shooting her in Jealousy, Italian Style for Ettore Scola, he embarked on a three-year romantic journey directing Vitti in three light-hearted romps, including Teresa The Thief and Blondes in Black Leather with Claudia Cardinale (the latter photographed by Dario Di Palma, Carlo’s nephew).

Vitti’s porcelain facial planes have never been more beautifully captured—she was surely drawn not only to Di Palma’s craft but his own personal style. “He was infinitely elegant, very erudite, and a bit snobbish,” notes another admiring director. The Italian press paid attention. Vitti was named Best Actress and Di Palma the Best New Director at the 1973 Golden Globes for Teresa. Little wonder Di Palma was selected as the lone documentarian permitted to photograph the magnificent Sistine Chapel’s ceiling paintings during its restoration—he had a boundless appreciation for both male and female beauty, and the world was beginning to recognize it.

Di Palma kept working—Bernardo Bertolucci’s Tragedy of a Ridiculous Man with its noirish tilted camera angles, Antonioni’s Identification of a Woman with the same kind of fog effects Di Palma had created near his beginnings, now shrouding Antonioni’s troubled terrains. When Vitti segued from Di Palma’s life back to Antonioni’s side, Adriana promptly took her place, where she remained through his lifetime.

Come to New York City and an American career working with Woody Allen.

Di Palma moved to Manhattan with Adriana for 17 years and shot 12 of Allen’s movies. “New York is for me my city, where I can feel almost like I’m in Rome. Manhattan has a European tradition and culture,” reflects Di Palma. It was here, with Allen, that his craft would blossom and radiate into countless cinematic directions.

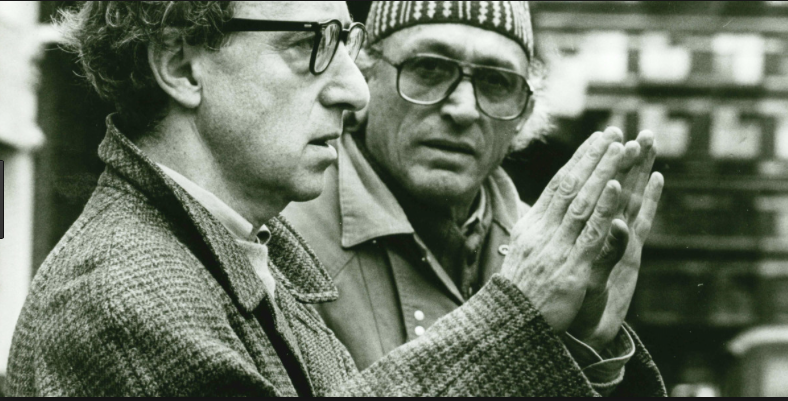

“He spoke not bad English—not great, but not bad,” remembers Allen of their first meeting. Says Di Palma: “He didn’t speak a word of Italian, and my English wasn’t much better.” But the two filmmakers clicked instantly. Allen seems to have sensed that Di Palma could provide workable solutions for any cinematic challenge and that, given the freedom, he’d innovate in ways that would make Allen’s stories look their best.

Water and Sugar shows scenes from Allen’s films that spotlight one Di Palma solution/innovation after another: The singular candlelight illumination in September; the 360-degree tracking shot around the three actresses at the dining room table in Hannah and Her Sisters; the lush, lovely intimacy of family members huddling together (perhaps before going in to watch their favorite radio program) in Radio Days; the jerky, hand-held camera flanking the discontented and disconnecting players in Husbands and Wives; the hilariously destabilizing moments in Deconstructing Harry when Robin Williams alone feels out-of-focus in a mélange of characters because he really has slid out of focus…the scene of actors flying above Manhattan in Alice, though we’re meant to understand the scene is totally illusory.

If you compare Di Palma’s work with Allen to other master cinematographers used by the director, like Sven Nyvquist (four films including Crimes and Misdemeanors and Celebrity), Gordon Willis (eight films including Manhattan and Annie Hall), and Darius Khondji (five films including Midnight in Paris and Irrational Man), there’s a distinct difference between their more formal, even stately compositions and careful pacing, and Di Palma’s more vigorous style of shooting. Di Palma’s camera is restless and exploring—he uses zoom shots freely, and things can get a little messy. Allen speaks candidly of how he and Di Palma would walk onto a set, neither knowing exactly what they’d be shooting that day or how. He hints at an improvisational quality on both their parts, not unlike Allen’s work on a bandstand with fellow musicians. It was a rare partnership.

Alec Baldwin summarizes what many marquee stars may have felt acting for Di Palma and Allen: “There’s an understanding that we’re here to make art, and that is as important as everything we do. Maybe more important. Carlo had a humanity, a feeling for actors as people. When you did a good take, and Carlo called ‘cut’, he’d communicate that you did a good job—(ALEC MIMES A TINY FLICKER OF APPROVAL)—and he’d whisper ‘verygood verygood’.”

Benefit from the kindness of strangers.

When Di Palma was a child growing up in Rome in the 1930s, his mother would entrust Carlo to the care of streetcar operators to transport him from her flower shop to near their home. In hot summers, if Carlo felt fatigued and thirsty, the driver would stop and bring the boy a cup of water, with just a touch of added sugar to boost his energy: Water and sugar.

Kamikari’s documentary weaves an impressive A-list of bold-face artists who add thoughtful tributes. Besides Pena and other fest heads, plus Allen, Bertolucci and Baldwin, the cast includes Michael Ballhaus, Abel Ferrara, Giancarlo Giannini, Ken Loach, Santo Loquesto, Mira Nair, Francesco Rosi, Volker Schlondorff, Ettore Scola, Paolo Taviani, Lina Wertmuller and Win Winders. Riz Ortolani contributed the uplifting music score.

Becoming a major film artist is a lifetime work-in-progress. Borrow from Carlo Di Palma’s past to build on your own future.

Water and Sugar shows at the Walter Reade theater in Lincoln Center Fri. July 28 (2:30, 6:30); Sat.July 29 (4:00); Sun.July 30-Wed. Aug.2 (2:00,4:30); and Thu Aug.3 (2:30).

Watch for Brokaw’s critical choices in The New York Film Festival, (Sept. 28-Oct.15).

Regions: New York City