New York Film Festival Sept. 28-Oct.15

Senior Film Critic Kurt Brokaw Picks his Best Narrative Dramas and Docs

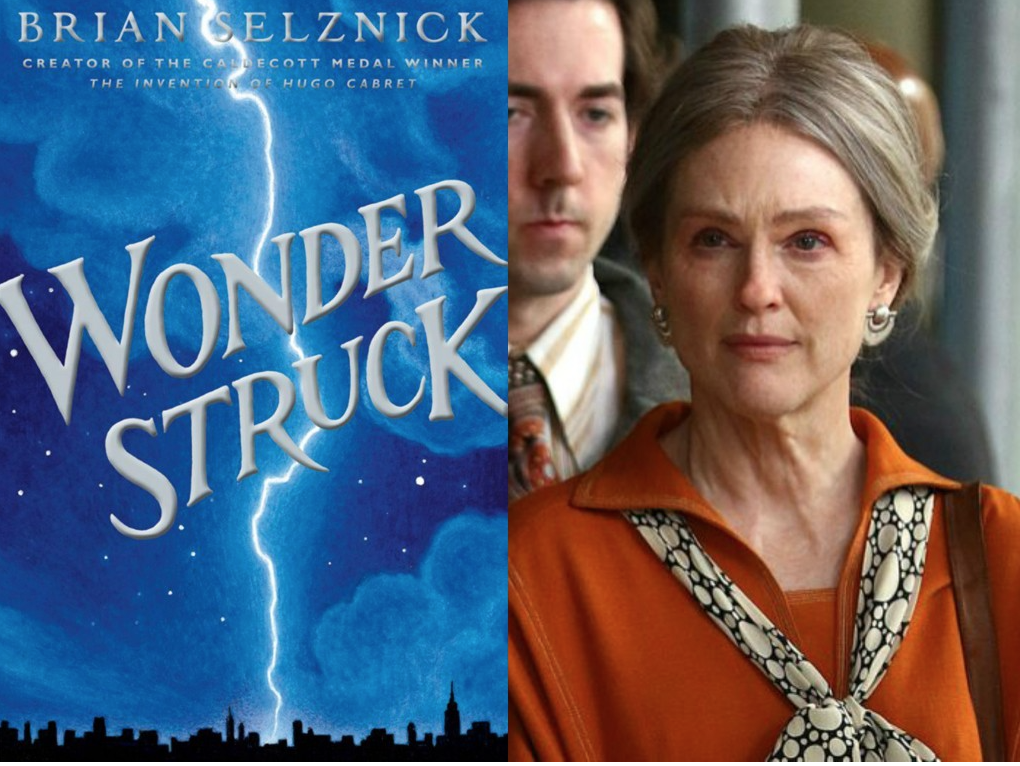

Wonderstruck; Todd Haynes; USA 2017; 117 min.

Leave it to Todd Haynes to pull off this festival’s most enchanting magic spell. In less than two hours, Haynes transforms Brian Selznick’s 640-page young readers’ novel into a cinematic bliss out of loss, longing, discovery and fulfillment. Take it from a father of four: Wonderstruck is the best reason to have children that the New York Film Festival has shown in 55 years.

The book. (Ben’s story.) Ben’s story is initially told entirely in words, not Selznick’s pencil drawings that fill 460 pages. The boy, who was born deaf in one ear, shares a home in rural Minnesota with his older brother, and is pursued by wolves in his dreams. His divorced mom, a local librarian, has recently passed away; his aunt and uncle care for the boys. Ben plays his mom’s favorite song, David Bowie’s “Space Oddity, “a lot. It is 1977.

Ben’s cousin gives him a coffee can filled with cash. He finds a book, Wonderstruck, published by the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. There’s a bookmark from Kincaid Books on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, with a short note to his mom, signed “Daniel” in 1965. Ben believes Daniel is his dad and would like to find him.

A fierce storm passes overhead. Ben is on the phone when a bolt of lightning passes through the telephone wires, deafening his good ear. Ben slips into a dream in which a wolf is running through the streets of New York. When he wakes a bus is dropping him off in midtown Manhattan. He walks to where the bookmark told him Kincaid Books would be, but it’s an abandoned storefront. Ben makes his way to the Natural History museum, where a whole new world (including those wolves) opens itself to him.

The book. (Rose’s story.) Rose’s story is initially told entirely in drawings, not words, starting in Hoboken, New Jersey in 1927. Rose is clipping pictures for her scrapbook of Lilian Mayhew, a glamorous silent-screen, moving picture star. From her bedroom window on the Hudson River, the deaf girl can see the skyline of New York City.

She goes to the local theater, which is showing “Daughter of the Storm” starring Miss Mayhew. The movie is silent with inter titles explaining that Lilian and her baby barely escape a storm that blows the roof off their home. Leaving the theater, she notes that marquee changing to advertise the coming of “Hoboken’s first sound system.” Arriving home, she finds a book left by her stern father, “Teaching the Deaf to Lip-read and Speak,” with a note from her tutor to study the book.

Rose spots her father reading a newspaper story announcing that Mayhew will be making her Broadway debut in a play. She packs a small suitcase and crosses the Hudson River on a ferryboat, making her way to the theater’s stage door in midtown, and slips inside. The actress is wearing a beautiful gown and rehearsing. She spots the child and is furious. Rose flees to Mayhew’s dressing room, where they write notes to each other: “What are you doing here?” “I miss you, Momma.” “I will send someone to take you home.”

Her mom locks her in the dressing room but Rose slips through a window and makes her way to the Museum of Natural History, where a whole new world opens itself to her.

The movie. Todd Haynes executes Selznick’s screen adaptation with all the craft and expertise he’s poured into period pieces like Carol, Far From Heaven and The Velvet Goldmine. The 1927 scenes with Rose (Millicent Simmonds) are shot silent in black-and white. The 1977 scenes with Ben (Oakes Fegley) are shot in color with in-and-out sound and a trunkload of arcane lenses and historical film stocks, researched and obtained by cinematographer Ed Lachman, that replicate with breathtaking accuracy what audiences were watching in 1927 as well as 1977.

Your senses adjust easily to this cross-cutting, because Haynes and Lachman make it so easy for you. Costuming, production design, the subtleties of sound and music slipping in and out, the clever transition devices, all urgently push you along. Like Seltznick, these are master storytellers and they can’t wait to show you what happens next.

The last half hour of the movie—on top of the last 150 pages of the novel not shared in this review (no spoilers here!)— will indeed leave you wonderstruck. Suffice it to note that Kincaid Books does exist in both print and on the screen, though it isn’t at 2750 West 74th (Selznick’s imagined address that would put it somewhere on the other side of the Hudson River). Standing in for Kincaid’s is Westsider Rare and Used Books at 80th and Broadway, which has been propped to the teeth with Haynes’ customary attention to detail, and becomes the perfect setting for Wonderstruck’s prime revelations.

Your critic can also safely report that Julianne Moore is a silent screen damsel-in-distress worthy of Lilian Gish in The Wind, as well as an aristocratic stage presence in the Katherine Cornell manner, rehearsing the tearfully melodramatic My Mother’s Advice. Moore also makes a significant third appearance, playing scenes that braid the deep complexities of Selznick’s novel into the most satisfying resolution you can imagine, as Manhattan suddenly goes to black on the night of July 13, 1977 (first caused by a lightning strike at a substation on the Hudson River). In this movie, art imitates life imitating art without a seam showing.

One should extend more than a pat on the head to young Millicent and young Oakes, as well as to Jaden Michael. The latter youngster befriends Ben and steers him to Kincaid Books’ new address, in addition to introducing him to backstage secrets at the Museum of Natural History, where his dad works. Michele Williams also leaves a positive and mysteriously troubling impression in a few early scenes as Ben’s mom; it’s little more than a cameo but it’s Williams’ building her chops and she’s a welcome presence.

And how can one praise Ed Lachman’s work highly enough? Again, suffice it to say this guy turns up at every advance showing of every film in this New York Film Festival, as he’s done for the past several years.The last industry figure who came to study and enjoy the entire main slate was actress Sylvia Miles, now 85, for some years. Lachman may not realize he’s become the new Sylvia Miles on the Upper West Side.

Joan Didion: The Center Will Not Hold; Griffin Dunne; USA 2017; 92 min.

“I was paralyzed by the conviction that writing was an irrelevant act,” says Joan Didion, who for many has been the preeminent journalist and essayist of both the 20th and 21st centuries. Griffin Dunne, her nephew, has fashioned a brave, all-stops-out, warts-and-all documentary of her bi-coastal life and times over half a century. On-camera, her arms sometimes waving with uncontrolled emphasis but her narrative razor-sharp and merciless, Didion narrates her seemingly endless life and career.

It’s a profession including scores of magazine articles, five novels, five screenplays, 13 books of non-fiction and a Broadway play, but it’s primarily an anatomy of atomization—a demonstration of how societal culture falls apart because the center will not hold. In Didion’s explorations, very little holds. She’s a specialist in “working the horror of disorder,” with “a predilection for the extreme” and especially “the wearying enigma of California,” where she seems to have come most alive when caught in the fast lanes of freeway traffic

This is not an easy documentary to watch, but like most of Didion’s long articles, novels and scripts for the screen and stage, you can’t take your eyes off the page or the image. She’s a precisionist, and even though she doesn’t quote her most famous line from the preface of Slouching Towards Bethlehem (“writers are always selling someone out”) she doesn’t need to. Alerted to a five-year-old child sitting at a party wearing white lipstick, stoned on acid, Didion doesn’t hesitate in saying “it was gold—you live for moments like this.” Asked why snakes appear frequently in her writing and even on Play It As It Lays’ book jacket, she explains if you keep a snake just inside your line of sight, it won’t bite. At 82, Didion can still be be very, very scary.

But we know she’s authenticating a history of our time, an America we came to partially understand and fear in fictional tales by the literary sages of our youth—Updike, Cheever, Oates, Roth, Bellow. She was, for some of us, an elite contemporary: Born in Sacramento and educated at Berkeley, she migrated to Manhattan after winning a writing contest that landed her a first job at Vogue. Anna Wintour reminds us the 60s were a decade when women wore hats and gloves, a time in which Joan learned action verbs and the importance of character. Run River, Didion’s debut novel of murder and betrayal in California, was published in 1963.

She was drawn to the movies of John Wayne, sensing he was the ultimate protector, the kind of man she secretly craved. Didion thought she’d found her protector in John Gregory Dunne, also a first-rate journalist and author of both fiction and non-fiction; they became each other’s muse, trusted reader, and co-screenwriter. Joan and John adopted a daughter, Quintana Roo, in 1966, later marrying. They moved to a series of homes in Los Angeles, from Franklin Avenue out to a Malibu oceanfront fixer-upper. (Fixed up by, of all people, a young carpenter named Harrison Ford.)

Dunne’s documentary bursts with these sidebar peeks into Didion’s life. She was drawn to the Haight and rock icons like Jim Morrison and Janis Joplin because “they lived their lives in front of you and never ordered ordinary drinks.” Covering the Manson killings in Roman Polanski’s house was difficult because “nothing was making sense.” Interviewing Manson cult member Linda Kasabian “seemed weirdly normal and yet not normal at all.” Polanski later spilled a glass of red wine on Didion’s wedding dress. Warren Beatty had a serious crush on her.

Didion, Gregory and their daughter moved back to Manhattan. Their troubled marriage strengthened. Didion and Dunne’s screenplay for Panic In Needle Park, set in the city’s then unruly Upper West Side, posited Romeo and Juliet as junkies. Didion joined The New York Review of Books; her piece on Dick Cheney captured what NYRB founder Robert Silvers called “all of Cheney’s deceiving, evil and bullying.” She wrote a definitive analysis of the Central Park Five, the young black men erroneously charged with raping and nearly killing a female jogger. (“I was waiting for Joan to write the piece I needed to read,” says New Yorker essayist and critic Hilton Als, another of the many astute talking heads, including Calvin Trillin and Susannah Moore, assembled by Dunne.)

And then twin tragedies struck Joan Didion: Dunne, 71, suffered a fatal heart attack in their home. Quintana, depressed and drinking heavily, had married five months earlier and was in a coma when her father died. Yet the daughter gathered the strength to move to California where she battled alcoholism, septic shock and pneumonia for 20 months before succumbing to acute pancreatitis at age 39 in 2005.

Events of this magnitude would plunge most biographical documentaries into a depression they wouldn’t recover from. That doesn’t happen here. Didion memorialized her husband in the memoir A Year of Magical Thinking and her play directed by David Hare and acted by Vanessa Redgrave, and devoted a second memoir, Blue Nights, to the daughter she believed she’d not sufficiently protected. Hare and Redgrave contribute meaningful recollections.

What we see emerging—and it’s a tribute to Dunne’s careful exposition, editing, and a subtly supportive music score—is Joan Didion becoming her own protector…working through her grief by writing about it. Her literary agent Lynn Nesbit calls the process “getting it down and then releasing it.” The latter journey—described by Didion as accepting she can no longer reach her daughter, that she’ll “fade from my touch,” fading as the blue light of summer Manhattan nights ebbs away, may be her closure to an indelible writing life.

The recognition has been substantial. In July 2013 Didion received the National Humanities Medal from President Obama, who noted his surprise that she hadn’t received it earlier. Part of that tribute penned by Maud Newton: “Whatever the genre, Didion’s writings are all unmistakably her own, both deeply individual—intimate, restless and withering—and culturally astute. Like Mark Twain, she works at the intersection of truth and absurdity, an uncomfortable place, one rife with the potential for humor but also for disillusionment, sadness and pain.”

The White House ceremony, with the president gently presenting a nation’s thanks to a chronicler of its times, lifts the movie immeasurably. We watch Didion back in her home, walking slowly away from camera and down a hallway, leaving us with the thought that she’ll be remembering “what it is to be me.” It’s clear this is one artist who won’t be forgotten.

Nice Girls Don’t Stay For Breakfast; Bruce Weber; USA 2017; 80 min.

The longest section in the festival’s 86 page program gives 14 pages to the Robert Mitchum Centenary. Imagine—that’s 12 pages more than the Film Society gives to its Opening Night, Centerpiece and Closing Night attractions, as it spotlights 25 of Mitchum’s major starring roles from 1945 through 1995, each of which contributes a laconic look-back at a Hollywood legend whose original ambition in life was to be a bum.

One of Mitchum’s most memorable lines is from Out of the Past, a seminal 40s noir in which bad girl Jane Greer tells him fearfully, “I don’t want to die.” “Neither do I, baby,” replies Mitchum, “but if I have to, I’m gonna die last.” He almost did, passing at 79 in 1997 from lung cancer (he was a lifelong Pall Mall Straights smoker) a day before his fellow screen icon James Stewart.

The esteemed fashion photographer Bruce Weber spent four years courting the reclusive actor, who turned down far more interviews than he gave, plying Mitchum with little gifts like Picasso art books and Russ Meyer movies. Weber was fascinated with Mitchum’s considerable singing prowess (he recorded two albums of ballads and calypso), and the director’s experience following jazz trumpeter Chet Baker in Let’s Get Lost (1988) may have won the actor’s interest. Baker sings on his fatal descent into heroin addiction, closing Weber’s doc with a whispered, tortured version of “Almost Blue.” Mitchum sings enough in these 80 minutes to fill a 10-inch LP.

Not that Nice Girls skimps on the actor’s indelible film work. There are clips from the essentials like Night of the Hunter, The Lusty Men, Pursued,The Story of G.I. Joe and The Friends of Eddie Coyle, plus lesser-known titles like Home From the Hill, Angel Face, The Apartment and Till the End of Time.

But you go to Nice Girls for the Bad Boy stories, and Weber’s rowdy, often slapdash exploration gathers some juicy ones. Sarah Miles, having been romantically used and discarded by Mitchum on the endless months shooting Ryan’s Daughter, cursed Bob out at a birthday party attended by his wife Dorothy, and stuffed a black dildo in the top of his birthday cake. Mitchum tells how he got ailing director John Huston, who was starving himself and not eating, to finally get his appetite back by posing a naked nurse in front of him. Then there’s Benicio del Toro who confesses the two scariest boogeymen in his life were Bela Lugosi in Dracula and Mitchum in Cape Fear.

Polly Bergen’s experience in Cape Fear, a superior revenge thriller, is the capper. She details her first shooting day with Mitchum, which was the film’s conclusion in which the homicidal maniac Max Cady (Mitchum) traps her and her daughter on a houseboat. Polly’s wearing a sundress with spaghetti straps, and Mitchum, bare chested and built like a bear, starts improvising stuff, breaking an egg he smears on her chest, slamming her through a wooden door, mauling her. The scene has an unplanned, uncontrolled fury and Bergen was truly terrified. When director J. Lee Thompson finally yelled cut, Mitchum instantly broke and hugged Polly for minutes, profusely apologizing to her over and over. It was then, Polly says, she fell in love with him.

Lots of women did. A friend confides that Elizabeth Taylor, who lived across the street from the Mitchums, brought his morning paper up to his front door, and once hid in the back seat of his car. Actress Frances Farmer clings to Mitchum like Elmer’s Glue in a restaurant scene, as the actor seems to be considering whether to slip her in his hip pocket. Golden Globe winner Brenda Vaccaro. A pillow-talk gal pal, laments that Mitchum told her “if I was going to leave my wife, I’d leave her for Shirley MacLaine.” Mitchum jokes “in my day, all we talked about was screwing and overtime.” But through it all, his marriage held together for 57 years.

Weber’s doc works hard to validate Mitchum’s boast that he’s “the last of the Mohicans,” which is his last line leaving the restaurant. Another director might have concentrated on his film work, as the Film Society does by integrating two dozen of his movies into its stuffed two week schedule. But Mitchum’s legacy rests on the casual rogue he played with equal ease both on and off-screen.

That’s why Weber’s most intimate views of Mitchum are when he’s singing. He partners Rickie Lee Jones perfectly on “Cheek to Cheek,” and holds his own alongside that most sinister of songbirds, Marianne Faithfull. His vocals on the wistful ballads “In the Morning, No,” “Sunny,” “Wild Is the Wind” and “Don’t Quit Now” are rendered with aplomb. Archival clips show him singing alongside the Ames Brothers and Jimmy Durante.

Johnny Mercer’s liner notes on the back of his album, That Man: Robert Mitchum Sings! nail his mercurial talents: “What some would call a maverick, I would call ‘a free palomino.’ His beat is impeccable, only a shade behind Bobby Darin, and if a note is too high for him, what the hell—he can act his way through it.”

BPM (Beats Per Minute); Robin Campillo; France, 2017; 144 min.

“Silence=Death.” You know that slogan because you’re seen it for decades. It was the original core positioning of the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP), founded in New York City in 1987. Its Paris branch started in 1989 and is the subject of Robin Campillo’s starkly realistic narrative drama, which often sheds or batters away its dramatic framework to achieve the chilling impact of a no-holds-barred documentary.

Campillo joined ACT UP in 1992 so he knows precisely how to script and stage the indoor planning sessions that intersect his story. ACT UP’s mission as a dedicated community was to convey emotional urgency to uncaring local governments, slow pharmaceutical companies and an uninformed citizenry. Its educational goal was persuading the world not just that LGBT people, drug addicts, convicts and sex workers, but anyone risking unprotected sex, may contract a progressive and ultimately fatal infection.

Everyone in ACT UP had skin-in-the-game, including the mother of a 16-year-old with AIDS, and BPM is a master class in the planning and execution of sit-ins and die-ins (known as zaps), protest marches, lobbying campaigns, promotion slogans and media stunts. The latter start with sending postcards of a dead member to President Mitterrand, and folding two sheets of paper a certain way that will jam a company’s tax machine, to sneaking into a gala corporate dinner and scattering the ashes of deceased friends and lovers over the buffet food tables. It was an all-out effort to “put the disease on the street” by all non-violent means. (We learn that to make 10 liters of blood, you mix 10 liters of water with one kilo of sugar plus wallpaper paste, then add red food coloring in three different shades.)

In its more passive interludes, the drama introduces a frank, tender and unusually mature snapshot of two ACT UP members in their mid-20s—Sean (Nahuel Perez Biscayart) and Nathan (Arnaud Valois)— falling in love, sensing at least one of them won’t live much longer. Campillo integrates their intense relationship with restraint; the couple’s moments of electro/techno disco abandon (from which Beats Per Minute takes its title) and deep-in-the-night intimacy never overshadow the film’s dramatic momentum. They become a vital underpinning to Campillo’s unsparing view that governments and corporations are indifferent to human suffering.

They also anchor the movie’s universal outreach. After their first coupling, Sean tells Nathan he was infected the first time he had sex, at 16, with a married math teacher he’d trusted. How he quickly became sick. How the math teacher gradually lost touch. How no one talked about what was happening. “Am I your first pos?” gently asks Sean. “You’re the first to tell me,” admits Nathan, who’s still testing negative. It’s one of the movie’s most poignant turning points, when we may start to recalibrate our feelings about the lives, loves and mortality of gay men.

BPM’s filmic authority is most evident in its clashes and confrontations: ACT UP whistle-blowing its way into a government-sponsored rally and drenching its spokesman with fake blood (thrown in balloon-like pouches) then handcuffing him to a railing. Another vivid scene shows the organization invading Melton Pharm and dousing their walls with blood and flyers until the police drag them out. In a third telling incident, we watch the activists marching into high school classrooms to distribute information and condoms. The responses from early 1990’s teens in a pre-Internet world are what you’d expect—one girl is shocked because she doesn’t “sleep with fags,” while another boy is grateful to receive information on safe anal sex.

In the seasons in which this movie’s events take place, ACT UP’s attention was focused on learning the trial results of a protease inhibitor that could attack virus duplication, thus becoming a possible alternative to debilitating drugs. In 1990 AIDS sufferers were desperately searching for anything more effective than AZT. The inhibitor trials involved no less than 16 lymph node punctures, resulting in profuse vomiting and diarrhea. Some members believed the trials should be declared invalid.

Other potential medical breakthroughs, or the necessity for extended research, are vigorously debated in ACT UP’S weekly meetings. Instead of applauding another member’s ideas, people click their fingers. The tension is heightened when one young man suddenly falls over from deteriorating blood work and waiting for his AZT to work. These scenes, performed by a dynamic and spontaneous ensemble, are intensely fascinating to watch. Until you register that it’s Adele Haenel—a competent French version of Kate Winslet who’s appearing to advantage in one Film Society festival selection after another—playing an ACT UP leader, you can’t be sure you’re not watching documentary footage.

As the activists’ activities grow in scope (there’s a spectacular long shot of the Seine River turned blood-red as far as the eye can see), Sean storms out of a meeting in despair—he’s getting weaker and sicker, and is hospitalized. He tells Nathan of his infection and reveals the Kaposi’s Sarcoma of cancer cell patches on his chest and neck. “I don’t know if it’s the fear of fear…but I’m afraid…all the time,” Sean tells Nathan It is one of their last moments speaking together.

ACT UP’s noble energies and efforts have lost none of their impatience and stature in 30 years. Their achievements in Paris have received a new kind of public recognition—BPM is France’s official entry for this year’s Best Foreign Film Oscar. Make it a viewing priority.

Mudbound; Dee Rees; USA; 2017; 134 min.

On October 22, The New York Times ran an editorial suggesting the revival of ticker-tape parades honoring people “we can celebrate in longed-for unity.” The paper noted there have been only 11 such parades in the past quarter century in Manhattan, and then went on to suggest possible honorees, including first responders, soldiers in the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, and cultural figures like poet Tracy K. Smith, actor/composer Lin-Manuel Miranda, and filmmaker Spike Lee.

Mr. Lee, the Times noted, “may be the best maker of New York themed films since Sidney Lumet.” Spike Lee is also the mentor of not one but two distinguished filmmakers in this fest. As artistic director of the graduate film program at New York University, Lee taught Kevin Wilson, Jr., director of My Nephew Emmett, the fest’s best short (reviewed here) and an easy contender for Best Short Oscar…and Dee Rees, director of Mudbound, the fest’s best dramatic feature which is aching to sweep next spring’s Oscars. Wilson’s short was coordinated and supported by Professor Lee, and Ms. Rees not only took his classes but was a production intern and assistant on two of Lee’s feature films.

Hillary Jordan, the novelist who created Mudbound, would probably have been pleased to have Spike Lee direct her tale of Mississippi farm life during and after World War II, but she’s going to be over the moon with how vividly Dee Rees has brought it to life.

The book. This is one tough novel. “When I think of the farm, I think of mud, lemming my husband’s fingernails and encrusting the children’s knees and hair, sucking at my feet like a greedy newborn on the breast, marching in boot-shaped patches across the plank floors of the house,” says Laura, a 31-year-old virgin in 1939 Nashville when she marries decent, determined Henry McAllan, age 50, and they move to a desolate piece of Marietta, Mississippi farmland. “There was no defeating it. The mud coated everything. I dreamed in brown.” Laura calls her new home Mudbound.

Laura and Henry move into three rooms owning little more than her 1859 Stieff upright piano and his John Deere Model B tractor. There’s no electricity or running water, and barely room for her hardbitten, racist father-in-law, Pappy. Their closest neighbors are a black family, Hap and Florence Jackson, who are share-tenants to Henry, paying a quarter of their cotton and soybean crops to him. Their son Ronzel, and Henry’s younger brother, Jamie, go off to war at the same time—Jamie will fly 60 missions in B-24 Liberators in aerial combat, Ronzel rises to sergeant in Patton’s 761st Tank Battalion.

Back in the Delta, it’s a hardscrabble life for both families, who are raising younger children as well. Hap is a self-taught reader who also weaves baskets and ministers to a small black congregation, Florence is a midwife—“tall, strapping, with muscles ropy as a man”— who does weekday chores for Laura.

Henry’s credos include “don’t lend anything” and “there’s no room for pity on a farm.” Pappy is an embittered elder who affects a cane, “a prop he used whenever he wanted to appear patriarchal or get out of working.” The two wives are drawn to support each other—when Hap falls off a ladder fixing his tin roof, it’s Laura who fetches the one doctor in town who can properly attend his broken leg.

The bonds between the families initially seem stronger when Jamie and Ronzel return from active duty and begin a loose, tentative friendship linked to their common war experiences. (Both of them have hands that still shake from combat.) Jamie’s become a heavy drinker with “whiskey on his breath and woman smell all over his clothes every Monday.” Ronzel sets off the local layabouts by attempting to use a grocery’s front door entrance, and makes matters worse by sitting up front with Jamie in the family truck. The black veteran also shares a souvenir of his days and nights overseas that falls into the wrong hands and sets off a series of destructive events to both families.

Mudbound was awarded the 2006 Bellwether Prize for Fiction, founded by writer Barbara Kingsolver and awarded biennially to a first literary novel that addresses issues of social justice.

The movie. The adaptation by Rees and Virgil Williams trusts and follows the novel in every important way. This is a considerable accomplishment, because the picture, like the book, has six narrators—Laura (Carey Mulligan), Henry (Jason Clarke) and Jaime McAllan (Garrett Hedlund)…plus Hap (Rob Morgan), Florence (Mary J. Blige) and Ronzel Jackson (Jason Mitchell). Everyone is on an equal footing as a first-person storyteller,and both family’s dramatic progressions receive equal screen time. It’s a daring novelistic device that immediately works cinematically and never let’s go.

In its acute and visceral visualization of World War II combat in Europe as well as its Klan-based violence in Mississippi, Mudbound is uncompromising and raw. It stops just short of the brutality that may have kept Kathryn Bigelow’s Detroit from reaching a wider audience (though hard-to-watch scenes didn’t harm the Oscar-winning 12 Years A Slave). Rees adds a healing scene at the very end that differs from the book’s more traditional and also upbeat conclusion. It’s probably intended to make Mudbound more Oscar-friendly, and it succeeds handily.

All six principals—plus Jonathan Banks’ archetypal rendering of the racist patriarch Pappy—seem to have been lifted off the printed page. Nearly a century ago this happened in movies with far more frequency; Henry Fonda and Jane Darwell as mother and son in John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath spring to mind, as do the youngsters playing Scout and Jem opposite Gregory Peck in Harper Lee’s To Kill A Mockingbird. Mudbound—both Jordan’s novel and Rees’ movie—stand tall in these same rarefied atmospheres.

In a perfect, lost world of movie distribution, Rees’ 134 minute feature film would show in theaters preceded by Walker’s My Nephew Emmett instead of 19 minutes of coming attractions. This feature and this short, set a decade apart in similar Delta fields, partner each other perfectly, though they had their New York premieres over a week apart in different theaters owned and operated by the Film Society of Lincoln Center. It’s a missed opportunity and will probably remain that way…though Spike Lee will know the fruits of his labors lit up this festival like blazes.

This concludes critic’s choices on features. Reviews on the fest’s outstanding shorts including My Nephew Emmett can be viewed here http://independent-magazine.org/2017/09/new-york-film-festival-sept-28-oct-15/ Watch for Brokaw’s reviews on the 8th annual DOC NYC documentary festival, showing in Manhattan theaters November 9-16.

Regions: New York