Tribeca 2019 Features & Docs Films: Critic’s Choice

Senior Film Critic Kurt Brokaw’s Top Feature and Documentary Films

Gay Chorus Deep South; David Charles Rodriques; USA; 2019; 100 min.

“There is a storm, and we have to learn to dance with the storm.” The storm here is not the tornado raging rampant through Southern states, but a resurgence of faith-based anti-LGBTQ laws. That’s why the San Francisco Gay Men’s Chorus (SFGMC) did a Lavender Pen bus tour last year through five southern states, performing in churches as well as community centers and a few concert halls. Imagine—25 shows in Mississippi, Tennessee, Alabama plus North and South Carolina. The SFGMC strategy is explained by its leader and conductor (whose father was a Southern Baptist minister and whose mother was a singer with Billy Graham), Dr. Tim Seelig: “Why are we singing religious music?” asks Seelig during a rehearsal of “Amazing Grace” in San Francisco. “Because in the South, you don’t make any kind of effective change without going to the church. For me, saying ‘I once was lost but now am found’ was the day that I came out. And the rest of my life has been about truth telling.”

Seelig is the complex, tenacious anchor of this exceptional feature doc debut by David Charles Rodriques. The chorus director is a quiet authority figure, the kind of man who listens more than he talks. He holds a doctorate from the University of North Texas, and has conducted at Carnegie Hall. His piano is surrounded by photos of “my favorite queens,” including Harvey Milk and Queen Elizabeth herself. Shepherding a bus tour into the Deep South, through his former social and professional milieus, is a role Seelig never imagined he’d play.

Director Rodriques pays significant attention to Seelig and two chorus members who’ve lived through terrible experiences in the South. The choir master tells a long, heartbreaking history of building a career as associate minister of music at a megachurch in Houston, as an outwardly straight married man and father who finally came out and was promptly fired—the church even financed litigation against him, making sure he’d lose his home after his wife moved away. Jimmy, a member of the chorus, speaks of his dad in Mississippi who told him at age 48 he wished his son had never been born. Another singer, Steve, tells of growing up in Birmingham where it was okay to be both homophobic and racist, and where his own late parents rejected him. For all three men, being gay was viewed as the ultimate betrayal.

These painfully articulated pasts never paralyze Rodriques’s doc, but they cast long, dark shadows. They also lend the film the possibilities of conflict and confrontations on the road. The director has nimbly mapped and edited the cinematic journey as a series of alternating pluses and minuses, wins and losses. Most instances involving a back-and-forth conversation—at a trans outreach seminar, in an alt-right radio station with a surprisingly sympathetic host, in a support group with a chorus member who’s transitioning, in a simple round circle of quilters—things move forward.

Jimmy reconciles successfully with his dad as well as other family members. An interfaith gospel choir from Oakland (representing 13 religions and with a membership that’s one-third LGBTQ) joins the tour and helps pave the way into churches that might have turned down an all-male chorus. A gay pastor—surprise!— thanks the bus riders for getting one parishioner who initially voted against his hiring, to give him a hug after the concert in their church.

But teenage Riley, who nervously hopes to get to a concert, reveals how her parents removed her from school to get her away from a trans teen she’d started to see. Another church with a minister Seelig says is both a homophobe and a bigot, refuses The SFGMC/Oakland offer to perform. Many churches in the Carolinas simply aren’t ready to welcome an interfaith choir flanked by 200 gay men. There’s one nasty warning by phone, and a few teens carry protest signs outside their church. “God is the Supreme Court,” reads an ominous parish sign off the interstate.

Gay Chorus Deep South inevitably will remind some viewers of this past year’s Oscar winner, Green Book. In that dramatic biopic, the African-American pianist Dr. Don Shirley (Mahershala Ali) tours his virtuoso classical and jazz talents through Southern states in the 1960s, encountering resistance and hostility almost everywhere off the concert stage.

In this documentary, Dr. Seelig is way beyond seeking a Southern veneer of hospitality and tolerance. He’s searching for real attitude shifts toward equal protection for the LGBTQ community, and he believes—ironically given his bitter experiences in the institutional church—it has to start with churchgoers.

An LGBTQ bus tour today is worlds apart from a drama of a 20th century black musician on a similar tour through Southern states. But director Rodriques is asking the same question Don Shirley was probably asking half a century ago: “If we open our ears, will our hearts follow?”

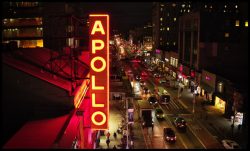

The Apollo; Roger Ross Williams; USA 2019; 98 min.

Harlem’s Apollo Theater and Tribeca’s annual film festivals have been uptown and downtown New York neighbors for 18 years. Part of the West 125th Street theater’s mission statement defines the Apollo as a “catalyst for new artists, audiences and creative workforce…envisioning a new American canon centered on contributions to the performing arts by artists of the African diaspora, in America and beyond.”

While Tribeca has added to its platforms over 18 years, embracing not just features but shorts, TV, online work, VR/AR and music, its mission continues the belief of co-founders Jane Rosenthal and Robert De Niro that “stories are the most effective tools we have to entertain, to educate, to inspire, to heal, and to bring us together.”

It’s been a long time coming, but Tribeca proudly opened its 18th fest April 24 with a full-tilt, exhaustively jam-packed documentary that in less than two hours captures the Apollo’s legendary past, vigorously celebrates its vibrant present, and—perhaps most urgently—hints at a relevant future bursting with new voices and expanded venues. Like Barry Jenkins’ rendering of James Baldwin’s If Beale Street Could Talk which had its premiere at the Apollo during last October’s New York Film Festival, the April 24 premiere of The Apollo unreeled on the big screen right above the stage it applauds.

The Past. It’s easy to sense that director Roger Ross Williams, who’s already won one Oscar, is an appreciator and an enthusiast, as he methodically works his way forward from 1934, piling layer on layer of rich archival performances. Let’s see, there’s young, promising vocalists like Ella Fitzgerald and Billie Holiday, comics like Moms Mabley and ‘Pigmeat’ Markham, dancers like Honi Coles and the Nicholas Brothers, orchestra leaders like Duke Ellington and Lionel Hampton, Amateur Night contestants like Lauryn Hill and James Brown, plus glimpses of and commentary by community and national leaders like Charles Rangel, Percy Sutton (who bought and renovated the Apollo), Adam Clayton Powell, Malcolm X, Rev. Al Sharpton and Rev. Jesse Jackson, President Barack Obama.

Williams has the passion of a completist (this doc had six years of editorial research and whipsmart assembly) and he’s anxious not to forget any Apollo name of importance, so he keeps returning to roots, integrating more and more legendary entertainment clips into—

The Past and The Present. Amateur Night is America’s longest-running talent show on any stage. It’s an acute, no-nonsense demonstration of how Harlem audiences possess the sharpest elbows, the fastest thumbs-down, and the biggest welcoming hearts of any New York audience in the city, maybe in the world. While everyday contestants aren’t auditioning to do seven shows a day like their elders routinely endured, “Be Good or Be Gone” is still the M.O., and there’s a “resident executioner” whose job is sweeping bad talent off the stage. (Showtime at the Apollo was a 21-year television series, produced by Sutton, with 1,093 episodes.)

Director Williams has engaged the Apollo’s keenest and most knowledgeable observers of this never ending phenomenon: Apollo CEO Jonelle Procope, executive producer Kamillah Forbes, journalist and educator Herb Boyd, Apollo host and guide (for over a half century) Billy Mitchell, professor and musicologist Guthrie Ramsey, plus original owner Frank Schiffman’s financial ledgers and terse comments on his booking cards. All these pros provide invaluable insights into the place “where stars are born and legends are made.” This is the history on which is built—

The Future. Toni Morrison has written that “I’ve been wondering who might fill the intellectual void that plagued me after James Baldwin had died. Clearly it is Ta-Nehisi Coates.” The voice and vision we’re drawn to most memorably throughout The Apollo documentary is neither an entertainer, an entrepreneur, nor an administrator. It belongs to author/journalist Coates, seen in rehearsal scenes as well as last year’s staged performance of his Between the World and Me. Written as a letter to his 15-year-old son, Coates takes his title from Richard Wright’s poem of the same name, published in a 1935 magazine, and won the National Book Award in 2015. It’s a portrait of the intimidation, fear and violence that’s forever been wielded against black people.

Coates, who’s 44, grew up in Baltimore, the son of a Vietnam veteran and former Black Panther. He graduated from Howard University and has been a national correspondent for The Atlantic magazine. (He also appeared in Tribeca’s feature length doc on the Wu Tang Clan, Of Mics and Men, giving excellent perspective on how Wu Tang Clan members have transcended poverty and invisibility growing up in the projects of Staten Island and Brooklyn.) Coates tells his son he didn’t experience the revelations of supporting a black president, nor “social networks, omnipresent media, and black women everywhere in their natural hair.”

From Coates’ onscreen prominence, It’s possible to conjecture that Williams sees Coates as the lineal link between The Apollo’s past, present and future. That the author’s staged work might one day be joined by that of Toni Morrison as well as so many neglected and marginalized black writers besides Richard Wright—James Baldwin, Ann Petry, Chester Himes, Zora Neale Hurston, Langston Hughes, Iceberg Slim, Clarence Cooper. That when the historic Victoria theater almost next door to The Apollo is restored and redeveloped next year, this new Apollo Performing Arts Center will include 25,000 square feet enclosing two performance spaces with 99 and 199 seats. Either or both might be a performing space traditionally known in theater as a black box. The Apollo’s dream future is woven into The Apollo.

Georgetown; C.Waltz; USA 2019; 99 min.

The impostor movie has always been an entertaining genre, as far back as 1961 when Tony Curtis acted a real-life multi-faceted con man in The Great Impostor, ending up assuming the persona of the FBI agent who’d been assigned to track him down. Or as recently as last year, when Oscar-nominated Melissa McCarthy played a real-life failed author in Can You Ever Forgive Me?, who becomes a rare ephemera dealer by forging letters supposedly written by famed dead playwrights and authors. Plausible impostor movies can be irresistible to watch, because often, as above, they’re inspired by true events.

Just days ago, The New York Times reported that a beautiful but destitute Russian immigrant, “with aspirations of becoming a member of Manhattan’s upper society,” was found guilty of reinventing herself as a German heiress who swindled banks and bilked patrons out of millions. The Times story, headlined “The Trial of the Fake Heiress Who Snowed Manhattan,” also noted that Netflix has bought the rights to one version of her story, with the producer of Grey’s Anatomy onboard.

Another future entertainment Torn From Today’s Headlines.

In Christoph Waltz’s Georgetown (directed by Waltz under a teasing “C.Waltz” abbreviation), the actor plays a fictionalized version of the smooth-as-silk German con artist, Albrecht Muth, who successfully passed himself off as an Iraqi general who insinuated himself into the upper echelons of Washington D.C. society. Muth hobnobbed with defense secretary Robert McNamara, billionaire financier George Soros, even supreme court justice Antonin Scalia. He claimed to know Dick Cheney and UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan on a first-name basis, playing the host at intimate dinners where he personally cooked and served roasted duck in bitter orange with venison pate. The movie replicates all this in delicious detail.

Muth started out a penniless, Ponzi-style schemer with a fast, Teutonic wit and a photographic memory, courting and in 1990 marrying the journalist and socialite Viola Drath, 44 years his senior. (Drath is played byVanessa Regrave, who’s 82 and acts a 91-year-old with vibrant ferocity). Muth became her butler and consort, using her as a door opener into Washington high society, though he regarded her more as a door stop, and called her “madam.”

While they slept in separate beds, Viola was Albrecht’s willing facilitator, charmed and flattered by his blue-eyed attention. She gave him a $2,000 monthly allowance. It took her a long time to realize she was being used and even abused, though Viola’s daughter, Connie Drath Dwyer, an astute LA judge, immediately sensed her new stepfather was a total fraud but was powerless to help her mother. (Redgrave’s daughter is acted with chilly, biting precision by Annette Benning, who’s as persuasive in the drama’s key supporting role as anyone you’ll view this year.)

In August, 2011, Drath was found dead, beaten and strangled in the posh three-story Georgetown row house which she owned. Muth told police he believed his wife had been mistakenly killed by Iraqi assassins; his curt statement to police included “I have to take a slain wife out to Arlington, bury her, and then find her killer.”

Drath’s murder is Georgetown’s opening, and the movie is a series of cat-and-mouse whodunit flashbacks. Like the very best impostor movies, this is a quicksilver entertainment of mounting intrigue and tension, enriched with a literate and visceral screenplay by David Auburn (Broadway’s Proof), as well as a glossy, opulent production via producers who get that sumptuous, luxe settings are vitally important to the menace.

Georgetown is the odd duck movie in this Tribeca festival, because it feels wildly out of place with its Hollywood stars and the kind of budget Megan Ellison often writes checks for. Waltz as usual tries to dominate another movie, just as he ran rampant in Quentin Tarantino’s Django Unchained and Inglourious Basterds. He’s barely in control again as he jackrabbits and motormouths his way through scenes with a slick, volcanic veneer that barely masks a gutter mouth and rageaholic temper.

Waltz could flatten and destroy lesser actresses than Redgrave and Benning, but both these powerhouses can equal and even best him, and C. Waltz, bless his crazy director’s heart, lets them. He even seems to encourage them. Redgrave’s fury at finding her husband at the Plaza Hotel in bed with another adult is something to behold. Ditto Benning’s merciless scorn and ramped-up horror of the man she believes may have killed her mother. Georgetown is quite the snazzy ride.

Other Music; Puloma Basu, Rob Hatch-Miller; USA 2019; 83 min.

Could all those people parading somberly through New York’s East Village be mistaken for a New Orleans funeral cortege? There’s a brass section of trumpets, trombones, saxophones up front, clearing the way, tooting a weirdly cacophonous version of “When the Saints Go Marching In.”

But this is a neighborhood of music loving New Yorkers, turning out on a June day in 2016 to mourn, of all things, the closing of a record store at 15 East 4th between Broadway and Lafayette. Other Music is a meticulously detailed, lovingly brushed-and-combed (and occasionally animated) history of that store’s 21-year run, zooming in on its last six weeks of operation. As a New York documentary, it stands shoulder-to-shoulder with Bill Cunningham New York, Joe Papp in Five Acts, Miss Sharon Jones and Blue Note Records: Beyond the Notes— authentic docs you crossed-your-fingers would get their beloved subjects right, and miraculously did.

Other Music (OM) was a no-nonsense, 750 square foot space that started as a pre-Internet source for 16,000 vinyl and CD titles you wouldn’t find in many shops—and especially not across the street at its massive competitor, Tower Records (which closed in 2006 with no parade). OM was a store “for people who still trusted the opinion of other people,” because they knew what they were talking about.

You could also read the staff’s opinions on handwritten note cards propped up next to favorites. Bands formed other bands which formed still other bands, thanks to being exposed to a vast panorama of Other Music’s indie rock, jazz, noise, experimental, funk, hip hop, electronica, roots, soul, dance, reggae, digital minimal and international pop (to name a few categories). What shoppers discovered, every time they walked in, were shelves of artisans who made music that was truly surprising.

Chris Vanderloo and Josh Madell, along with Jeff Gibson, seeded Other Music while working at Kim’s Video Underground in the early 90s. Kim’s was a tightly curated collection of rare, experimental and bootlegged VHS movies. Chris and Jeff were the guerrilla record guys in the back room. They saw how the movie operation was infinitely more geared to downtown New Yorkers’ tastes than anything Blockbuster could imagine stocking. They also surely observed that some Kim’s staffers weren’t (to put it mildly) the most welcoming movie buffs. So when they decided to set up their own retail operation in ’95, they figured being across the street from Tower might be the perfect spot— with a passionate staff that could run rings around Tower employees.

Directors Basu and Hatch-Miller allot major screen time to OM’s incredibly knowledgeable and friendly workers—Jim, Pamela, Geoff, Gerald, Scott, Katie, Dave, Michael, JoAnn, Maris, Chris, Phil, Amanda, Jenny, Duane,Nicole, Daniel, Clay, Pamela, Tunde ,Karim, Lisa, Dan, Regina, Stephanie, Brendan, Karen, Josh’s wife Dawn, Chris’ wife Lydia, and more. This sounds like an impossible payroll to meet, but no one was getting rich, including the owners.

Like its founders, OM’s staff was heavy with full-spectrum music listeners who spent their nights covering the local music venues. Some were working musicians. Half the expert staff were women…something you rarely saw (or see today) in any record store. At Other Music, personal service was the magic elixir. Friendships with customers formed in the ’90s, years before friending was something you did on a device.

While there could be an elitist quality to the music—as there certainly was to the obscure movies at Kims Video— it rarely trickled down to the OM seller. One thing you feel strongly in this beautifully crafted doc is that seller and buyer were comfortable striking out together in uncharted waters. “Other Music symbolized something that I find important,” remarks Matt Berninger of The National: “If your bar on art is high, then your bar on kindness is high. When art and movies and TV get dumber, we all get dumber and meaner.”

The store became a tiny in-store performance space for artists like Revlon 9, Beans, Vampire Weekend, Mogwai, Yo La Tengo. St. Vincent, Lee Renaldo, Gary Wilson. It launched a mail order website in 1998 and an online MP3 store in 2007. Other Music provided the first distribution outlet for dozens of New York composers, songwriters and bands who’d burn their own CDs and bring them in on consignment. Getting your own name card in an OM bin was, for many who make music, a recognition of the highest order.

OM’s best year was 2000, and 2001 was on target to beat that—then 9/11 struck the city and its downtown neighborhoods. It was the beginning of the end for many, many mom-and-pop walk-in businesses. (Composer William Basinski, a good friend of the store who’d worked with Antony and the Johnsons, created “The Disintegration Loops” with a slowly dissolving analogue spool that paid a respectful, ever changing elegy to the tragedy and its after-effects.)

While Other Music didn’t encounter a calamitous rent hike, the growing dominance of the Internet in the first decade cut deeply into CD and vinyl sales. A lot of music lovers quickly grew accustomed to not paying for music. In 2003 we learn the store didn’t make any money. “Conversations online began to replace conversations in the store,” recalls Nicole. Ironically, when Tower Records packed it in, a fair amount of foot traffic drawn to the block also disappeared. The East Village was no longer the hub of the music scene—it was, summarizes Josh, “disconnected from it.” The combined losses weren’t sustainable.

The last two days, with its “everything must go” signs and customers lining up—finally—to haul home bargains, is filled with a soft vulnerability and tearful hugs. The filmmakers stay close in, but somehow maintain a respectful distance. Emptied out, OM becomes another “Space To Let.” New York City will forever go on reinventing itself, and its music, but Other Music had an unforgettably innovative run for over two decades. In this town, that ain’t bad.

Watch for Brokaw’s reviews in The New York Film Festival, Sept. 28-October 14, 2019.