New Documentary: “Toni Morrison: The Pieces I Am”

Senior Film Critic Kurt Brokaw Salutes 2019’s Must-See Biography

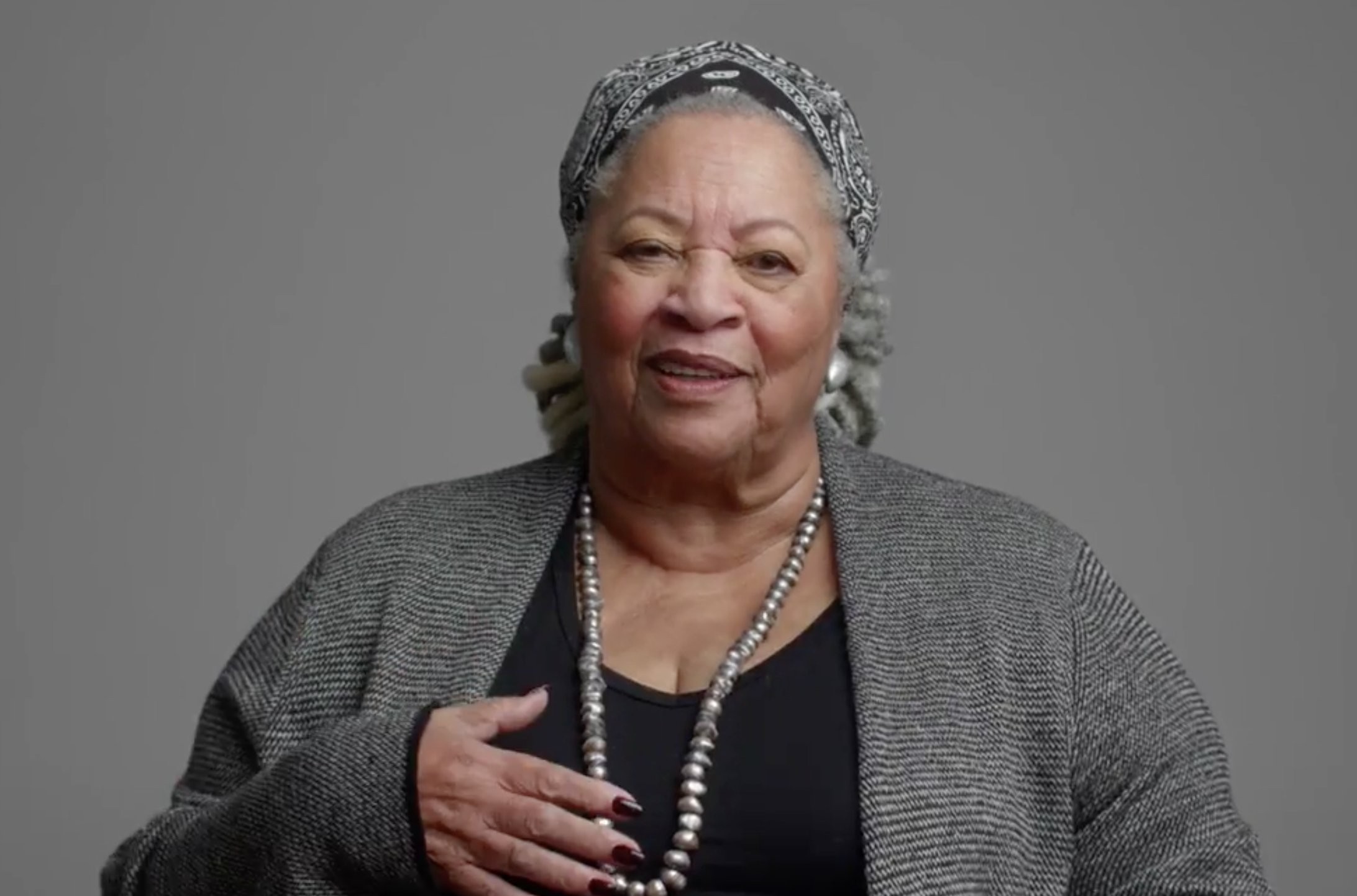

You’ll be conscious from its opening seconds that the preeminent novelist Toni Morrison—unlike all the other distinguished writers, poets, editors and academics gathered for this stirring literary biography—is staring directly at you when she speaks. Just as in the still above.

And she speaks a lot—probably more than any other subject of a feature-length biopic since 2015, when Brian De Palma conducted a sit-down 110-minute master class (titled De Palma) on how the Hollywood system bent but hasn’t broken him through decades of creating shivery scare pieces.

Morrison offers eye-to-eye contact in all of her sit-down scenes newly created for this documentary. It’s a natural choice for director Timothy Greenfield-Sanders, who’s both an acclaimed portrait photographer as well as a skilled documentarian. It’s especially striking upfront, as she makes clear how she eliminated the ‘white gaze’ from her writing—the tendency of African-American storytellers to assume their readership would be primarily white people. She first explained it in a 2009 interview in Oprah Winfrey’s magazine:

“From my perspective there are only black people. When I say ‘people,’ that’s what I mean. No African-American writer had ever done what I did—none of the writers I knew, even the ones I admired—which was to write without the white gaze. This was brand new space, and once I got there, it was like the whole world opened up, and I was never going to give that up.”

Morrison wants you to know she originated this “brand new space” with confidence and pride. Her manner most often is infectious, disarming, mischievous, instantly appealing. She has a big, hearty, approving, empathetic laugh. It’s a piece of oral emphasis she adds to dozens of observations. The more Morrison describes pieces of her life at age 88, the more you want to hear. “I like her,” she’s said of her own on-camera scenes directed by Greenfield-Sanders.

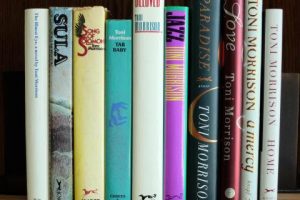

Right from the start of her 11 novels, beginning in 1970 and extending through 2015, Morrison began removing the white gaze from her approach. “It’s what Jimmy Baldwin called ‘the little white man that sits on your shoulder’” she tells us, and she flipped him off her shoulder nearly half a century ago.

Morrison has drilled down into the lives of black women over four centuries— a child raped by her father; a woman who sleeps with her best friend’s husband; women enduring conventional lives in Michigan and Virginia communities; a cook and butler, married, locked in pleasant servitude; a woman who kills her tiny daughter rather than see her slip into slavery; pre-Depression Harlem women carving out wild existences; an Oklahoma household of women caught in Civil Rights strife; a mother and daughter lost in an abandoned seaside hotel; farm orphans in the late 1600s; children on a brutal horse farm; sexual abuse in the lives of a young woman with pitch black (Morrison calls it “blue black”) skin and her lighter-skin mother.

Fearsome concepts. Fearless novels. Except for her exposition on Beloved, Morrison doesn’t do much explanation of her often harrowing plots. The director has assembled a wide, deep bench of literary lions to interpret and assess her artistry. The author’s main job is sharing and narrating the half century of her life before she became a full-time writer, which is a full-tilt documentary adventure in itself.

A reader by age three, Morrison (then Chloe Wofford) was raised in Loraine, Ohio. Her grandparents were Alabama sharecroppers who’d moved north from Birmingham as “white boys began circling” black children. Her mother was a domestic worker, her dad a welder.

“We were poor when poverty was not shameful,” she remembers. Drawn to the local library, Morrison was hired to catalogue books.

By the time she enrolled at Howard University, she’d changed her name to Toni because few folks could properly pronounce ‘Chloe.’ She majored in English but preferred the drama department because her English professor refused to let her write a paper on four black Shakespearean characters. She pledged a black sorority, not realizing she’d picked the one that preferred “lighter-skinned blacks.” After graduation, she took a master’s degree at Cornell, then returned to Howard and married an architectural major, divorcing him six years later and taking on the responsibility of raising their two sons.

Morrison responded to a mail order ad for an editor at the L.W. Singer textbook company in Syracuse, and got the job. She earned a raise, telling her male boss “I am head of household, just like you. When he said, ‘yes, but—‘ I repeated myself: ‘I am head of household…just…like…you.’”

Serendipity—Singer was acquired by Random House, and Morrison moved to Manhattan. She would eventually link up with Robert Gottlieb, who was building his career through Simon and Schuster into Random House’s premiere imprint, Alfred Knopf. (Gottlieb has edited all but one of her novels.)

Through Morrison’s nearly 20 years at Random House, she edited autobiographies by Angela Davis and Muhammed Ali, along with books by Toni Cade Bambara and Gayl Jones. One after another, her own novels starting with The Bluest Eye in ‘70 and Sula in ’73, began to appear. Author Paula Giddings, who was at Random House typing The Bluest Eye, was immediately struck with the alliances Morrison formed with black female authors, as well as the close friendships between women in her novels.

In ’74 Morrison completed assembling and published The Black Book, a sprawling cross between a scrapbook and a museum, what critic Hilton Als calls “a jumble of black American life” from slavery to modern times.” (“It was more like planting a crop than making a book,” Morrison has written, and it includes the history of an enslaved woman who killed her own daughter, later to become Morrison’s core concept of Beloved.)

Plus she was also raising her sons and commuting to Princeton University to teach literature and writing, where she’d tell students not to write about themselves (“you don’t know anything”), but instead to create a story about a Mexican girl who doesn’t speak English who works as a waitress in Houston.

How did she do it all? Morrison credits her family and relatives with a lot of loving help. For years she got up before dawn, and mornings are still her best writing hours. Angela Davis remembers her jotting constant notes when they were commuting to work together into Manhattan. Morrison’s primary residence today is a converted boathouse overlooking the Hudson River in Rockland County. She bakes a legendary carrot cake. Author Fran Lebowitz assures us she loves presents.

Morrison has won the National Book Critic’s Circle Award (for Song of Solomon) the Pulitzer Prize in Fiction and the American Book Award (for Beloved), the National Humanities Award, the Presidential Medal of Freedom (presented by President Obama), and the Nobel Prize for Literature (“they really know how to give a party in Stockholm.”).

These honors echo the accolades from colleagues and fellow writers. The late John Leonard, former editor of The New York Times Book Review, was the first cultural critic to recognize The Bluest Eye as “history, sociology, folklore, nightmare and music…her angry sadness overwhelms.” Novelist Russell Banks uses the metaphor of a pyramid of white male writers capped by Hemingway, Faulkner and Fitzgerald, finally being toppled by Morrison. Walter Mosley (the Easy Rawlins creator) speaks of her work as Shakespearean in its drama and tragedy, “while staying reflective of everyday, pedestrian black lives.” Harvard professor David Carrasco says “she’s the Emancipation Proclamation of the English language.”

Some tributes are deeply personal. Poet Sonia Sanchez chokes up as she reflects on “a white light around Toni, that some people you know really are the blessed ones, that they are put here to make us review ourselves, so we can walk, finally, as human beings.” Oprah Winfrey recalls the line spoken by a character at the close of Song of Solomon, “And she was loved’—that’s the anthem for any life, Toni captured the essence of what it means to be alive, and to have done well here on earth…and we can say the same thing for her, ‘And she IS loved.”

Besides Timothy Greenfield-Sanders, two artisans working overtime fitting the pieces together are Johanna Giebelhaus and Kathryn Bostic. Editor, researcher and co-producer Giebelhaus has knit dozens of original black paintings into vivid, cinematically enriching vignettes. One example: Both Morrison and Columbia professor Farah Griffin make the point that black writers long felt themselves expected to write for white audiences. There’s a moment when Morrison is critical of Ralph Ellison’s monumental novel, Invisible Man. “Invisible? Invisible to who?” challenges Morrison, and the image Giebelhaus chooses as counterpoint is Kerry James Marshall’s “Past Life,” one of the most buoyant and alive paintings of black women, children and men enjoying a picnic, boating, water skiing and golfing in one glorious mosaic.

Bostic scored Clemency, already The Independent’s lead review in the 2019 New Directors/New Films fest. Here she’s building a tippy-toe bass line, moody motifs, aching laments—plus a final vocal/piano/keyboards Bostic original, High Above the Water, boasting the kind of gospel stride and soul windows that organist Shirley Scott once splashed around.

The combined power of Morrison’s career pieces makes you rethink the old Hollywood chestnut, “If you liked the book, you’ll love the movie.” Try this Summer-of-2019 variation: “Whether you’ve read all or none of Morrison’s books, you simply must meet the author.”

Watch for Brokaw’s reviews in The New York Film Festival, Sept. 27-Oct.13.

Regions: New York