Checking Out “The Celluloid Paper Trail,” the Ultimate Guide to Screenplays

Senior film critic Kurt Brokaw reviews Kevin Johnson's new book on the long paper trail of 20th century scripts

There used to be a guy selling movie scripts in Manhattan, from sidewalk tables on lower Broadway and around Soho. Big screenplays like Avatar, Fight Club, Reservoir Dogs and Star Wars. They were clean photocopies, bound with metal brads, each priced at $15, and some of the script covers had their original color tints. Nice gifts or learning tools, right? But lately the tables have disappeared—maybe there just weren’t enough budding screenwriters left in New York City, let alone readers of screenplays.

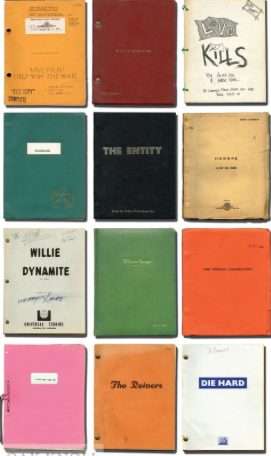

Kevin Johnson, who runs a rare book store and site, Royal Books in Baltimore, sells original movie scripts. Several of his current offerings include Luis Bunuel’s signed production script of Nazarin (1959), $25,000; John Lennon’s script of How I Won the War (1967), $8,500; and Paul Schrader’s 1983 early draft of what would become Martin Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ (1988), for a mere $1,750. These are high-end collectibles, and their target markets aren’t budding screenwriters or casual readers of screenplays. If you’re an indie filmmaker or film student, chances are an early or even post-production copy of your own screenplay isn’t quite ready for the window of Royal Books. But one day it might be.

Johnson’s already authored The Dark Page (2009), two huge, magnificent volumes showcasing original 30s and 40s cloth crime novels that became seminal films noir. They’re gorgeous books, crammed with fascinating book-to-screen insights—scholarly treasures for anyone partial to hardboiled gumshoes, femme fatales and the early crime fiction that grew them.

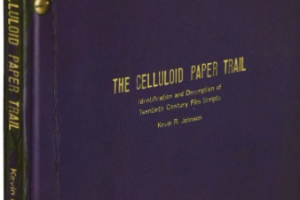

Now Johnson has authored a deeper, more descriptive guide to film script identification: The Celluloid Paper Trail (Oak Knoll Press, 2019). At $65 it’s a luxury purchase your deep pockets producer (ha!) or nearby university library (more likely) might want to invest in. It’s jam-packed with 130 examples of easily recognized American and British films in nearly every genre, documenting phase after phase of script development.

That paper trail can feel endless. Before Johnson’s landmark research and organization, one of the few guides to the torturous journey screenplays can take was offered by the late journalist and screenwriter, John Gregory Dunne, who was married to writer Joan Didion. His 1997 memoir, Monster: Living Off The Big Screen, detailed how one of their screenplays moved through no less than 27 drafts, over an eight-year period, before becoming the commercially successful Up Close and Personal.

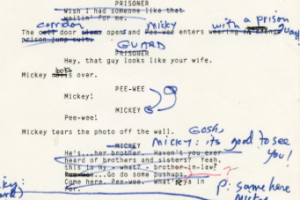

Johnson’s two foundations of determining a script’s marketplace worth are artifactual value and content value. The first is usually linked to the person who owned the screenplay, like the screenplays above that belonged to Bunuel, Lennon and Schrader. John Wayne’s personal copy of The Searchers, stamped with his initials and folded in half because that’s how he carried it in his pocket during the making of John Ford’s western, is a prized artifact. The heavily annotated script page shown here belonged to Paul Reubens, when he made Pee Wee’s Big Adventure for Tim Burton in 1985.

Content value references not who owned it, but its relevance to its time— socially, culturally and politically. For example, pre-Code dramas of the 1930s like Baby Face, I Was a Fugitive From A Chain Gang, Freaks and Red Dust pushed boundaries audiences had never experienced in movies. Otto Preminger refused to cut the word “virgin” from his comedy The Moon Is Blue (1953) or powerful drug scenes from The Man With The Golden Arm (1955)—releasing both films without a Code seal from the Motion Picture Association of America, even though the MPAA believed newspapers wouldn’t advertise such pictures and theaters wouldn’t show them. (But they did.)

The Celluloid Paper Trail concentrates its study on 1920s-80s screenplays. The number of script versions is staggering: story scripts become treatment scripts become first draft scripts leading (eventually) to final draft scripts which become budget estimating scripts, shooting scripts, revised shooting scripts, storyboard setup scripts, post-production scripts, ‘souvenir’ scripts, and for-your-consideration award scripts. Most of these variants exist in some form for produced films, and many scripts preceding production also exist for films that never made it to the screen at all.

Johnson defines multiple aspects of provenance and pagination—the wrappers, bindings, holograph notations, even methods of duplication (carbons, mimeo, offset, Xerox). Different studios had their own typefaces, bindings, templates and paper stock, with the poverty row indies (PRC, AIP, Monogram and Republic) often striving to look as good as the Selznicks and Paramounts.

The author devotes seven pages to supporting actor Charles Bickford’s 1945 copy of Fallen Angel, a tawdry Preminger drama with Linda Darnell and Dana Andrews romancing around a studio set pretending to be a California diner. Harry Kleiner adapted the novel (which was retitled Blonde Baggage in its 25-cent paperback reprint) by Marty Holland, who was actually Mary Holland, an ambitious studio secretary who also penned the story that became the Barbara Stanwyck noir, The File on Thelma Jordan.

Bickford’s annotations in pencil are scattered throughout Fallen Angel’s 135 page final draft, which has blue titled card wrappers, bound internally against a tab with two brass brads. The studio’s distribution page notes that “a charge of $5 will be made to you if it is not returned within a reasonable length of time to Room 14, Old Administration Building.” Presumably this did not include actor Bickford, a solid pro who quietly plays a former New York City detective who also has his eye on the sultry Darnell in the diner, shortly before her sudden demise. Hollywood is full of secrets.

Regions: New York