DOC NYC Film Festival Nov. 11-19 – Critic’s Choices

Senior Film Critic Kurt Brokaw selects top features and shorts from the U.S.’s largest documentary festival

Consider for a moment what’s been recently showing in two very different movie-going Americas.

On Oct. 30 The New York Times reported that the Park Plaza Cinema in Hilton Head Island, South Carolina, had just opened Liam Neeson in Honest Thief to 72 patrons. “It was the largest single-day attendance the independently owned five-screen theater had seen since reopening in August after a five-month shutdown,” noted the Times. “The next day only 22 people showed.”

At that time, the 11th annual edition of DOC NYC was preparing to virtually roll out more than 200 films and events—including 23 world premieres, 12 North American premieres, 7 U.S. premieres, plus nearly 90 short films. “Documentary filmmakers are an integral part of NYC’s creative economy and production community, and their ability to capture and communicate the human condition is so important during these challenges,” stated Anne del Castillo, head of the NYC Mayor’s Office of Media and Entertainment.

One could speculate that folks in Hilton Head had tired of Liam’s endless escapades, this time playing a guy who’s robbed 12 banks in seven states but decides to return the money. And maybe the hardworking couple who manage Park Plaza Cinema bet on Honest Thief as the one surefire thriller to lure Hilton Head’s movie fans away from the security of their living rooms and into a darkened theater. Perhaps it was the only new commercial movie with a proven box office name available that week. This critic’s columns don’t knock Hollywood and Hollywood-style entertainment. But they point to the growing importance (and, thanks to streaming, instant availability) of movies that inform and educate and challenge and advocate. Documentary features and shorts do all that. Sure, some are “entertainments,” as Graham Greene used to call his twentieth-century novels and the movies made from them. But others can be permanent markers in our lives, with the best docs teaching and reinforcing fundamental truths.

Women In Blue; Deirdre Fishel; U.S.; 2020; 89 minutes

A series of memorial images of George Floyd are shown in the opening seconds of Fishel’s Women in Blue. For this viewer, it’s the #1 takeaway doc in the 2020 edition of DOC NYC. Janee Harteau, the former Minneapolis police chief and 30-year veteran in the force, provides the voice-over: “For me, having spent most of my adult life as a member of our police department, leading that police department, I was questioning everything I had known. My goal as police chief was making change from within. Was I naive? Was I optimistic? I think I was both.”

It’s an eye-opening, attention-grabbing opening. Fishel is ready to roll out a penetrating, up-close-and-personal history of Harteau’s police force beginning in 2015. At that time just 16% of her officers were women. Excessive force complaints against female cops in Minneapolis were rare. A powerful union was protecting officers from termination. Harteau witnessed community protests at a local precinct after the 2015 death of an unarmed Black youth, shot by two white officers. The police chief allowed the protests to continue. She saw a real need and opportunity to change the organization, even after three independent investigations exonerated the officers. So she promoted women into every rank in the department. But she didn’t last long: when a Black officer killed a young white bride-to-be on a summer night in 2017, Chief Harteau was fired by the mayor.

At this point, with Harteau being replaced by a Black male officer (promoted four times by his former boss) who adds no women to his executive team, director Deirdre might have folded her tent and edited Women In Blue into a 30-minute lesson on failed police leadership. Instead, she continues a bold and intensely interesting pursuit—tracking what happens in and out of uniform to a rookie officer (Erin Grabosky), an officer (Alice White), the Commander of Internal Affairs (Melissa Chiodo), and an inspector and precinct head (Catherine Johnson), all reporting to a Black Chief of Police (Medaria Arradondo).

Officer Alice White—at the time one of six Black women out of 850 officers in the force—had been chosen to anchor Minneapolis’ participation in a new national training program. We watch her reset the professional parameters for involvement in traffic accidents and domestic flare-ups, sometimes “dealing with rapists and murderers.” White’s teenage daughter isn’t shy about telling her mom how this caused some estrangement from her classmates. Both are proud of White’s promotion to Sergeant in Minneapolis’ highest-crime precinct, but fusing open, collegial relationships with her white officers is a delicate balancing act.

Inspector Catherine Johnson knows the imperative is there for culture change, especially in the 3rd precinct known for its aggressive policing. Her challenge is getting the police to get citizens the help they need before hope is lost. She’s faced with rebuilding both community safety and trust, without female perspectives at the top. Plus she’s facing a 50% reduction of beat cops in a volatile neighborhood. (One notes the police union president has a one-sheet of Al Pacino in Scarface right beside his desk.) It’s not surprising when Johnson, a 22-year veteran, tells her staff she’s accepted an outside job offer.

Commander Melissa Chiodo is adjusting to her new post—she’s been transferred from running Special Crimes like domestic abuse and sex trafficking to being responsible for office discipline. It’s a painful education process she undertakes, one precinct at a time. She’s frustrated trying to recruit more women into police careers in which, as she frankly states, “women are viewed as either a mother, a bitch, or a whore.” When the Black officer involved in the bride-to-be’s death is charged (and later convicted for her death), she faces an avalanche of public outcries for white offices to be similarly brought to justice for a multitude of injustices, including homicide, against people of color. Later she applies for, and gets, the job as chief of police in another community.

Rookie Officer Erin Grabosky is worried whether the new mayor, Jacob Frey, may want to take guns away from cops. We watch her capably handle a series of street encounters that don’t quite turn violent, then an after-hours respite with her father, a retired police officer. He’s proud of his daughter, because in her three years on the force, she’s “learned not to take any bullshit,” but he also cautions her she’s got 31 more years before retirement.

Which brings us to George Floyd’s death this May. Catherine Johnson, looking at a sign in an abandoned lot that’s been altered from “Minneapolis Police” to “Murderous Police,” muses whether she would have been able to halt the burning of the 3rd precinct station had she stayed in charge. Inspector Johnson tells her daughter she cried at her desk over Mr. Floyd’s death. Johnson’s daughter supports her mom. So do hundreds of members of the Black community, women and men and children she knows by name.

Fishel told Ms. magazine (May 2020) that her documentary is not simply a call for gender equity, but an exploration of how “gender, race, and violence in American policing” are inextricably linked. The director believes the dots aren’t yet being connected by institutional authorities, nor are women being given leadership roles in helping transform police departments. “I think women can be part of culture change that puts communication, service and care first,” said Fishel.

Harlem Rising; Rayner Ramirez; U.S.; 2020; 108 minutes

Ramirez wrote, directed, and photographed this inspiring documentary, whose subtitle—“a community changing the odds—cues you it’s a key solution to the challenges faced by neighborhoods of color in the United States.

Harlem Rising promptly introduces its primary narrator, Geoffrey Canada, the 68-year-old, third-degree Black Belt president of the Harlem Children’s Zone (HCZ). Canada succinctly lays out HCZ’s non-profit mission: breaking intergenerational poverty and supporting the children living in 97 blocks of Central Harlem from birth through the lower, middle, and upper school grades, then college, and into meaningful work.

Canada was a child of the South Bronx streets, who found his way to the enlightened halls of Maine’s Bowdoin College and its African-American Society in 1970. Academic leaders there tasked Black grads to go forth, return to their home environments and create change. Canada got the message. He joined the Rheeden Center for Children and Families in Harlem in 1983 as education director. Right away, he was back next door to children living in families below the poverty line. He observed that more Harlem youngsters knew the community’s leading drug dealer and his gun culture than knew its leading political firebrand, Adam Clayton Powell. He sensed New York City’s War on Drugs, with its mandatory five-year sentences for possession, had no chance of deterring the spread of heroin.

The educator moved fast. Harlem Rising is a how-to instruction manual of achieving tiny but essential victories. Canada installs trained social workers, poetry curriculums, video equipment to preserve youth-produced programs and forums. His neighborhood target was kids ages 5-12, the goal motivating parents and grandparents to keep their children and grandchildren in school, no matter what. Canada taught karate and other martial arts to kids for free, not to break bones but to mold character. He piled in family events, after-school activities, drug-free block parties, community gardens, safe centers that stayed open seven days and nights a week. Former students were hired as “peacemakers” and mentors for bus trips up to Bowdoin, as well as organizers of peace marches on Harlem streets. Breakfasts became available from 6:30 a.m., because “hungry children will get there as early as possible.”

Canada searched tirelessly for “hook-em-up” dollars to replace “lock-em-up” dollars. With an endowment of $24 million, he founded the Harlem Children’s Zone with its two Promise Academies and a sibling Baby College, a preschool that starts offering support to toddlers “from crib all the way through college.”

Ramirez powers this history along with energy and dispatch. His on-camera testimonials are largely by graduates of HCZ’s Promise charter schools—women and men who stayed the course, graduated from colleges and universities, and moved into careers in finance, education, medicine, law, media and entertainment. Canada is the spark plug and faithful messenger, a trusted servant who keeps telegraphing urgent information in multiple directions. He’s easy to listen to and to agree with. President Obama became a fan and helped expand the HCZ model into 52 additional communities.

One triumphal and prescient moment occurs in a 1994 Senate hearing on crime prevention for at-risk children. Sitting next to Canada, Patricia, a fifth grader, has just finished reading a moving poem. A youthful and admiring Joe Biden asks her if her girl friends think “it’s a cool thing to do when you go over after school and hang out at the (HCZ) Center.” Patricia gets the last word, “One of my friends was mad she couldn’t go, too.”

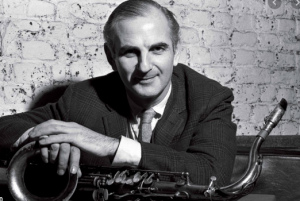

Ronnie’s; Oliver Murray; U.K.; 2020; 103 minutes

Do you miss live music? Who doesn’t. The warmth and intimacy of a small club where you’d gather with friends to listen to live music is—well, irreplaceable. This edition of DOC NYC has a number of worthy substitutes, but the one that combines a riveting biopic with an unmatched compilation of clips that’ll blow away any jazz fan, is Oliver Murray’s Ronnie’s. That’s Ronnie’s as in Ronnie Scott, the estimable tenor saxophonist whose orchestras and combos topped English lists in the 1950s… and Ronnie Scott’s, the West End club that this tireless bandleader launched in 1959 to be the performing room for world-renowned jazz greats. Scott (1927-1996) left a legacy that’s been preserved and honored, and Ronnie Scott’s is still going strong today in its original Frith Street premises, even as its new owners learn to survive virtually.

As the son of a Jewish sax player whose early career goal was “becoming a rear gunner in the Royal Air Force,” Scott vaulted into performing life in Ted Heath’s post-war dance band. Heath was the mirror of America’s Stan Kenton, and the two equally popular bands made exchange visits. Scott was entranced inside Manhattan’s string of jazz clubs along West 52nd, absorbing how swing music had transitioned into improvisational jazz led by legends like Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis, and Art Pepper.

Impatient with the predictable ensembles he fronted in London, Scott and a fellow horn player, Pete King, formed London’s first jazz spot. Their concept had never been tried before: Importing America’s leading edge musicians—from Buddy Rich, Mary Lou Williams, and Sonny Rollins to Oscar Peterson, Dizzy Gillespie, and Roland Kirk—and putting them on with English stalwarts like Cleo Lane and Johnny Dankworth. The formula worked instantly.

Ronnie Scott’s didn’t charge much, poured generous drinks, served reasonably priced food, and paid its performers well. King, who ran the business side, realized this business model wasn’t remotely sustainable. Scott wasn’t bothered; he was living his dream, playing “A Night In Tunisia” alongside Ben Webster, and segueing into a jokey M.C. persona that patrons found amusing. Infusions of financial support came from music moguls like Chris Blackwell of Island Records. What few people, other than Scott’s wife and children, sensed was that Scott’s artistry as well as his innocent comic intros were masking a monstrous depression. Ronnie acknowledges that “musicians can handle other musicians’ drug and alcohol problems,” but sharing mental illness in the 60s, 70s and 80s was strictly off-limits. Most of the time Scott is the only on-camera talking head—an unusual editing choice that works unusually well.

Ronnie’s is 103 minutes long, but it holds at a finger-snapping tempo, filled with one jaw-dropping number after another, and enhanced with color camerawork that’s often spellbinding. What’s most impressive is that a lot of these phenomenal performances are by legendary women: Sarah Vaughan’s mesmerizing “Passing Strangers;” Nina Simone’s poignant you-need-a-friend-you-got-a-friend “For A While;” Ella Fitzgerald sashaying through the mischievous “Mon Homme” with her call-and-response not to the bass player, but to his instrument. One contemporary artist, heralded by the new owner Sally Green, is the North African/soul jazz fusion ensemble Ajoyo, featuring Yacine Boulares. And surely the surprise pairing in this cavalcade of legends is Van Morrison warbling (with a crib sheet) through “Send in the Clowns,” backed by Chet Baker’s whispery trumpet while Baker looks like a stiff breeze might carry him out the door and clear over to Leicester Square. This doc’s a keeper.

Three Shorts Long In Meaning…And Heart

43 short films (in 8 thematic programs) plus 46 student films demonstrate how shorts have grown in importance in New York’s top film festivals. Nearly all were made available for upfront viewing, and your critic watched every one choosing three, the first examines the work of a pioneering Black filmmaker who brought feature-length African-American experiences to screens for the first time. The second is an intimate portrait of a Black Manhattan photographer, an octogenarian who’ll take your picture with an antique camera almost as old as he is. And the third is a history without a single spoken word, visualizing how one block in Brooklyn has changed in over a century. Remarkably, the first two are distinguished as “homework” by graduate students working toward advanced degrees in filmmaking.

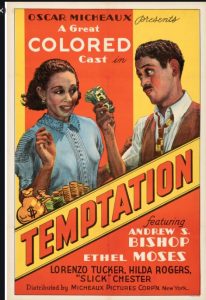

Changing The Narrative: The Vision of Oscar Micheaux; Eric Straight; U.S.; 2020; 19 minutes

A poor midwestern farm kid who migrated to Chicago and found work as a Pullman porter, Micheaux (1884-1951) found the rare opportunity to travel America by rail at the turn of the century, observing American culture. He saw and heard Black women and men satirized as minstrels and denigrated in songs (“Coon Hollow Capers”) and motion pictures (D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation) as sexually aggressive primitives that needed reining in by white supremacists like the Ku Klux Klan.

Michaeaux found his early voice in print, returning to rural homesteading roots in South Dakota and writing novels that dramatized the teachings of Booker T. Washington. His first, The Conquest: The Story of a Negro Pioneer, was a 1913 autobiographical tract that showed how a railroad porter could save up $2,500 to buy his own land on which to farm, prosper and marry a preacher’s daughter. He self-published a thousand copies and sold them door-to-door. Six years later he formed his own movie production company and adapted The Conquest into The Homesteader, the first feature film by an African-American. He would make 44 more movies over a 30-year career.

Writer/director Eric Straight uses silent and sound clips that show how the self-taught Micheaux pushed back against Birth of a Nation’s racist fabrications of the Black experience in his second feature, Within Our Gates. At that point the fledgling filmmaker sensed he had an even more important calling— a clear path to writing and filming the richness of Black life, without any competition, in a brand new medium. He never looked back. His urban doctors, lawyers, educators, musicians, singers—many acted by strong Black women in leading roles—became the first independent alternative to an industry dominated by white men. Micheaux was fascinated by interracial relationships and stories “that crossed the color line.” Like Griffith, he had no hesitation at filming on New York streets. He gave his sprawling tales intriguing titles like Lying Lips, Temptation, Murder in Harlem, Harlem on the Prairie. He introduced Paul Robeson in Body and Soul.

Straight has crafted a ground-breaking thesis film for his degree in Documentary Film at Brooklyn College. It includes learned commentary by Shades of Truth’s producer and director Michael Green, plus NYU professor Alrich Brown. Its music score by Oscar Peterson, King Oliver, and Duke Ellington keeps the movie scenes flowing smoothly. In 19-minutes he shows how one filmmaker gave generations of African-American audiences the treat of watching something they’d never seen before on the big screen—themselves.

Nine Days a Week; Maliyamungu Muhande; U.S.; 2020; 16 minutes

In cooler weather he wears his three-quarter length leather coat, over a natty suit and tie, topped with his signature leather hat—a solidly built 80-year-old Black man who’s usually leaning against some city wall, “waiting for someone who wants to talk to me.” He’s an uptown man who mostly works downtown: outside B&H Camera on Ninth Avenue, sometimes along West 18th, and occasionally in Grand Central Station. He has New York eyes that read and identify a possible customer out of hundreds of passersby. What draws in the visitor is his gleaming Speed Graphic press camera from the 1940s, with its armatures and flashbulb at the ready. It’s huge. He looks like he’s waiting to take some movie star’s picture, except the camera’s all wrong. Is it possible this guy is waiting to take an instant Polaroid of you, or the two of you, or your entire family, that he’ll develop before your eyes?

Meet Louis Mendes, who’s been working city streets for decades, though it seems forever. Like other New York institutions—the late Bill Cunningham who had an eye for the fashionable stroller, or the late Moondog, the Viking of Sixth Avenue, or the dapper chap in the beret who still pedals his bike up and down Broadway with Edith Piaf singing away out of a Pignose amp—Mendes is one of 1,001 reasons some of us moved to New York for in the first place.

His camera, acquired in 1959, is the same one hauled around town in the 1940s by the famous crime photographer Arthur (Weegee) Fertig. Weegee’s rig had a Kodak Ektar lens with supermatic shutter and used Super Panchro Press B film. Mendes narrates a hard scrabble, hard travelin’ life with episodes of homelessness and seasons in the shelters, then finding a passion he could develop “nine days a week” that’s given him a living and a modest home. His neatly arranged bookshelves might have stocked A Photographer’s Place, the late bookstore on Mercer. The man knows his craft. He’s also training up a cadre of young Black photographers who’d like to follow his lead.

Muhande, a Congolese filmmaker and art director, shoots his story in crisp wide-screen and black-and-white. It’s part of her work earning a Graduate Certificate in the School of Media Studies at The New School, and it’s going to earn her a place in every photographer’s heart on the planet who sees it.

Urban Growth; Nate Dorr, Nathan Kensinger; U.S.; 2020; 14 minutes

Some DOC NYC neighborhoods hold onto their pasts longer than others. In particular, Brooklyn has a long history of preserved secrets—abandoned properties, some in ruins, a few in prime waterfront locations, that have eluded or defied the wrecking ball. Dorr and Kensinger’s treasure is an ideal summation of how documentarians show us the vivid contrast between past and present. Urban Growth tells its story in visuals, without a word being spoken, wisely letting the viewer decide whether this a reality to be mourned or celebrated or accepted or even ignored.

The stealth imagery begins with the night photo shown, adjacent to the location of what was known for generations as Admiral’s Row, near the Brooklyn Navy Yard. On Flushing Avenue, near Navy Street, once stood ten ultra-fashionable homes built in the second half of the 19th-century. Designed for naval officers and their families, they were occupied by military personnel until the mid-1970s—long after the Navy Yard itself was closed. Not modernized or sold, the homes simply sat, decaying into ruin. The camera moves in on the image shown, one house projected above a modern-day storefront, and moves inside.

Against a quiet, contemplative score by Dorr (who co-directed, photographed, and edited with Kensinger), Urban Growth invites us to inspect the architectural bones, staircases, and rooms of these splendid homes. The camera roams, just as JR’s cameras recently prowled the still-standing Ellis Island Hospital at the tip of Manhattan, in his superb short Ellis. There is history infused with mystery in these places. Archival photography of the fully furnished homes invite us to contemplate how Brooklyn life was once lived on this eloquent block with its river views.

Alas, this engrossing cinematic tour, neatly compressed into less than ten minutes, concludes with the demolition of the homes in 2016. The block is anchored three years later by a vast supermarket and sizable parking lot. An end destination for countless shoppers. Any native New Yorker will give you an instant opinion on this change, but the filmmakers’ strict neutrality is never once in question.

This concludes the critic’s choices. Watch for Brokaw’s picks in the 49th annual New Directors/New Films festival, Dec.9-20.

Regions: New York City