The New York Jewish Film Festival Jan. 13-26, 2021

Senior Film Critic Kurt Brokaw selects (virtual) favorites

Sure, it was sorely disappointing not to view the 24 narrative dramas, documentaries and shorts up on the big screens at Lincoln Center’s Walter Reade Theater. That’s where NYJFF, co-sponsored by The Jewish Museum and Film at Lincoln Center, shows its annual festivals. But the real loss for this viewer—an irreplaceable loss—came in not being able to eavesdrop on a core audience of subscribers, ages 50 and up, who attend the films, patiently lining up on Broadway afterward and boarding the M104 bus on their way home. That’s where the nitty-gritty verdicts on the new movies get delivered on Manhattan’s Upper West Side.

The riders are a mix of couples, singles and widowed—Holocaust survivors and public school teachers, civil rights workers and organizers, union activists and “red diaper babies.” New Yorkers who support the vast panoramas of Jewish cinema, year after year. Which is not to say they love ‘em all. Sharp elbows sometimes prevail over generous hearts. As the bus meanders its way up Broadway, across 72nd Street and heads up Riverside Drive, the occasional selection gets shredded like wilted lettuce. But the ones that are loved, get loved permanently. And if they’re lucky enough to find an indie distributor, they get recommended forever. So here are three critic’s choices, hopefully in sync with a home viewership (this time only, please) always worth listening to:

Shared Legacies: The African American-Jewish Civil Rights Alliance; Shari Rogers; USA; 2020; 95 minutes

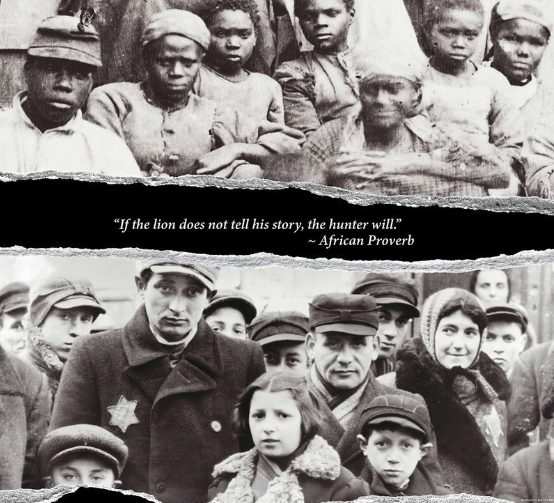

This is Rogers’ debut feature as director/co-writer/co-producer, and her onscreen credit reads “Dr. Shari Rogers, Ph.D.” We’ve never seen that distinctive directorial branding…but then we’ve gotten used to “A Spike Lee Joint” over the years as Lee’s way of announcing a film you’d damn well better pay attention to. In years to come the Rogers name is sure to identify the learned intellectual who put together the first doc on how Black and Jewish leaders formed and expanded a coalition of mutual interdependence. It’s a newsreel like newsreels once were in theaters—full of recorded events you watched, sometimes for the first time, before the movie.

The work of Shared Legacies is demonstrating—through 20 impeccably organized and tightly fashioned chapters, kind of a cinematic PowerPoint—how this fusion began in the early 1900s and reached its apex in the 50th anniversary march on Selma in March, 2015. Each chapter has its own name and date—“Legacy Stolen,” “It Can’t Happen Here,” “A Seat at the Table,” “Selma.” It was at the 50th Anniversary in Alabama that Rogers, a student of the Torah and friend of Clarence Jones (personal counsel to the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.) began rolling her cameras and assembling her seminal doc. Half of the 20th century and 150 captured hours, sculpted down to a brisk 95 minutes. There are eight other feature dramas and documentaries in the festival that movingly address anti-semitism in a variety of styles and settings, but as a history of Jewish oppression interwoven with Black repression, there’s not another film like it.

Talking heads, if they’re the right talking heads, can narrate a compelling documentary better than anyone. And Rogers has gathered an A-list of bold face names whose knowledge and insights are staggering. Rabbis and ministers, giants of government and letters and foundations and the entertainment world. They tell truths big and small, known and unknown, funny and terrible and sometimes both. Rogers and her editor, like any smart teachers, have chosen Lonnie Bunch III, Secretary at the Smithsonian, to begin the doc recalling how as a Black youth, the only girl he was allowed to partner in a school class on ballroom dancing was the one Jewish girl.

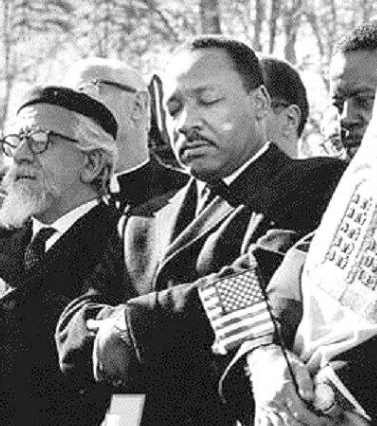

What becomes quickly apparent is that the two preeminent leaders who strengthened the bonds between peoples were Dr. King and Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel. The men shared speaking platforms and walked together in the 1965 Selma to Montgomery march for voting rights. Both Martin Luther King III and Dr. Susanna Heschel bear eloquent witness to their fathers’ closeness and unity. When Heschel passed in 1972, four years after King’s murder, the ecumenical bonds they’d painstakingly forged began to fade from the civil rights movement as well as Jewish causes. Shared Legacies is very clear about this. In its final minutes, Rogers’ doc doesn’t hesitate to acknowledge the long term effects of their absence, noting the corrosive rise of antisemitism and the tragic results of police brutality.

Rogers adheres unfailingly to her single objective of affirming, over and over, how Blacks and Jews found common ground. She’s stated her belief that her film has enough warmth and connectivity that Blacks and Jews “will feel safe enough to have open dialogues.” Indeed, listening to, learning from, absorbing the wisdom of seldom-seen pillars of society like Maya Angelou and Harry Belafonte, Congressman John Lewis and Union Theological Seminary’s Rev. Dr. Donald Shriver, museum founder Jawana Jackson and Israel’s first Bishop, Dr. Glenn Plummer—what better way to start a new year at the movies?

Minyan; Eric Steel; USA; 2020; 118 minutes

Steel achieved notoriety worldwide for a transfixing, oddly beautiful 2006 documentary shot on the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco. He’d persuaded the bridge authorities to grant permission to position hidden cameras on both land-based sides of the bridge for all 365 days of 2004. They believed he was filming a documentary on national landmarks, capturing the bridge’s majesty in changing light through all four seasons. But Steel’s goal was to capture all the suicides off the bridge that year. Fifteen camera operators with telephoto lenses actually got 23 of 24, with Steel digging into the backstories of six, including one who barely survived the swift currents. As a debut feature, The Bridge is probably the most terrifying doc even made on last exits from alcoholism, cross-addiction and mental illness.

Minyan is Steel’s first dramatic feature, and it validates his years working in publishing at Simon and Schuster and for Scott Rudin. He understands the imperative of finding the perfect story—here by the Canadian author David Bosmozgis—to adapt. “Minyan” won the Silver Award in the 2003 National Magazine Award for fiction. Set in 1987 in the section of Brooklyn’s Brighton Beach heavily settled by Russian Jews, the film is a coming-of age drama of exquisite delicacy and depth. It’s also a coming-of-age gay drama, a rarity in films immersed in the Hasidic community.

David (Samuel H. Levine) is the obedient yeshiva teen of immigrants who haven’t quite found their piece of the American dream. His mother Rachel (a fine Brooke Bloom) was a dentist in Russia who’s been reduced to assistant status and sees her own patients after-hours, his father Simon (Gera Sandler, ideal as a bruiser) is a former Russian boxer who’s become a physical therapist to widows. David’s grandfather Josef (Ron Riflin, splendid as always) is mourning his wife’s passing. He’s urging David to attend his synagogue, or at least become part of the ten man minyan (the number required for an act of sanctification) that meets daily for prayers. It’s the classic kid-drawn-into-a-web-of-family-tradition. David is bored. He’s drinking from his parents’ vodka bottle on their top kitchen shelf. And he’s casting glances at a gay bartender in the Village, not to mention other men on Brighton beach, in the library and in the school’s shower room.

A subplot layers in two widowed men, Itzik and Hershel (Mark Margolis and Christopher McCann, each skillfully drawn) who are Josef’s next-door neighbors in a rent-controlled oceanside building. They’re in a committed relationship. Rabbi Zalman (Richard Topol) is the resident building manager who assigns new apartments from an endless waiting list when someone dies. The rabbi may move Josef or David to the top of his list if David agrees to joins his grandfather in the minyan. The youth is more interested in his sexual relationship with Bruno the bartender (an excellent Alex Hurt), even though Bruno keeps a growing list on his kitchen wall of friends either in hospital or dead from AIDS.

Steel adroitly interweaves these disparate and complex elements with the ease of a veteran director. Perhaps his experience dealing with so many real-life deaths in The Bridge guided him in handling the cycle of life in Minyan, looking back with tears of compassion and deep understanding.

James Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room, and other seminal Baldwin novels, also flank David’s enlightenment. Levine’s towering performance, which anchors every minute of the film, is never more fully realized than in one classroom lesson. He’s interpreting the moments in Go Tell It On The Mountain in which the young John falls on the threshing floor of his Harlem church and begins to cry, not as an act of being reborn (as a female classmate suggests), but something deeper: “John knows he has to talk about being saved, with his father. The music he hears in his ears, what he feels inside, is a secret, still. But he isn’t a stranger to himself, anymore. He can see inside himself.” David is interpreting Baldwin’s character but he’s also proclaiming his own self-realization to his class, his teacher and himself. The awed one-word response from his instructor (Chinaza Uche), whispered up close to the camera, says it all: “Revelation.”

The Crossing; Johanne Helgeland; Norway; 2020; 90 minutes

The shadow of World War II hangs unusually heavy over this edition of NYJFF. Eight feature dramas and documentaries including Irmi, Kindertransports to Sweden, Who’s Afraid of Alice Miller? Winter Journey, The Sign Painter, The Red Orchestra and Adventures of a Mathematician concern Jews and Jewish families trapped in or fleeing Nazi persecution. They’re all urgent, worthy dramas and docs that hopefully will find an audience. Singling out The Crossing as the one critic’s choice doesn’t signal artistic superiority here. Partly it’s a recognition that these days, a hopeful ending in any war-related film is a grace note.

Johanne Helgeland’s drama is something else, too: one of the few war films that can be recommended as a starter drama for younger, inquiring minds. NYJFF’s notes call it “family-friendly,” and its super-glossy production, simplified English subtitles and a cast of four likable and convincing moppets make it all that. It’s respectful to its factual roots, with a dedication to “the 771 Norwegian Jews deported by the Nazis” including 100 who escaped, those who helped them, and those who perished.

Christmas, 1942, three years into the occupation of Germany. Anna Sofie Skarholt and Bo Lindquist-Ellingsen play a non-Jewish sister and brother who are the children of resistance parents. Samson Steine and Bianca Ghilardi-Hellesten act a slightly younger Jewish brother and sister. (All four are making their first screen appearance in Helgeland’s debut feature.) The Jewish children are hidden in the home of the resistance parents. When those adults are seized by the German authorities, the quartet of children decide to try escaping to Sweden—first by train, then hidden in potato sacks in a truck driven by a sympathetic teen, finally on foot through snowy woods.

They narrowly escape detection in a Nazi roadblock, as well as in an encounter with an outwardly friendly elder who feeds them as she secretly summons the Gestapo. Storm troopers and dogs are in close pursuit of the kids during the final perilous leg of their journey, and Helgeland sleekly integrates pulse-pounding music and spectacular helicopter shots that pinpoint the chase and the children, slip-sliding their way down through winter woods into a neutral and welcoming Sweden.

The Crossing is a brand new Norwegian film with an ancient and honorable Hollywood pedigree—MGM’s The Mortal Storm, released in 1940. That film was a cautionary tract, a warning against the anti-semitism that was festering though Europe. Playing pacifist students, James Stewart and Margaret Sullivan crossed the Alps and skied down into safer territory, also pursued by German troops. That picture enraged Hitler enough to ban all MGM films from being shown in Germany throughout the war. The Crossing, secure with its first-rate distributor, Menemsha, will fare much better.

Holy Woman; Emily Cheeger; USA; 2020; 20 minutes

Let’s lighten up. If you were a film student, could you possibly think of a less commercial short film topic than a comedy set in a Heredim community? Don’t tell that to Emily Cheeger, who grew up in Finland but has lived in Brooklyn’s Boro Park for the past seven years, making Holy Woman as her MFA thesis film in NYU’s Graduate Film Program. This little maverick movie has already won the award as Best Short Film at the Toronto Jewish Film Festival. It’s a hoot.

Neshama (Melissa Weisz, letter perfect) is singing to herself as she dresses for evening prayer at shul. “It’s not proper to sing while unclean,” her husband Shaya (Luzer Twerksy, ever fretful) reminds her. Later, as Neshama nibbles some salmon with the ladies, we learn Rabbi Mordechai of Kolnitz (pictured above) was a fine cantor when young. Suddenly he chokes on a bone and dies. In the fancy animation sequence that follows, the fish in Neshama’s body morphs into a baby, which grows a beard before your disbelieving eyes.

Days pass and Neshama spouts facial hair and consults Shaya. “Shave it off in the mikveh,” he advises. The female attendant begs off because “it may not be kosher.” Then Neshama begins mouthing the Rebbe’s commands: “No cutting, no plucking, no shaving!” As she grows a chest-length beard, she’ll sing away in the Rebbe’s splendid young voice. The men in the congregation are baffled—some feel it hardly matters whether the holy voice is coming from him or a woman, but most march out of shul when Neshama takes over the service. Writer/editor/director Cheeger has a bag of mystical tricks up her cinematic sleeve—she’ll braid faith and gender questions as two souls link to one another in completely unexpected and surprising ways. Neshama takes her name from “soul,” for good reason.

Holy Woman (Tzadelkis in Hebrew) is the sleeper short of the fest, a knockout gem lovingly conceived and smartly produced on a Kickstarter budget that somehow grew to $50,000. That’s a miracle in itself. Emily’s on her way.

This concludes critic’s choices. Watch for Brokaw’s picks in Rendez-vous with French Cinema, March 4-14.

Regions: New York