New Directors/New Films, April 28 – May 8

For its 50th annual festival, Senior Film Critic Kurt Brokaw picks four new releases reflecting a half century of viewing, plus a pandemic.

The conventional wisdom on a conventional 50th anniversary festival would be to first applaud the curators who brought world class filmmakers like Kelly Reichardt and Pedro Almodovar, Spike Lee and Michael Haneke, Wong Kar-wai and Guillermo del Toro, Hou Hsiao-hsien and Agnieszka Holland to audiences far and wide, starting way back in 1972. No one in the New York movie industry deserves a victory lap more than the curators, past and present, at the Museum of Modern Art and Film at Lincoln Center. In addition to the 27 features and 11 shorts being presented now at MoMA virtual cinemas and in-theater at Film at Lincoln Center through May 13, an additional 11 retrospective features are being given free virtual showings to MoMA and FLC members.

Still and all, there’s no escaping the reality that returning to big screen viewing in a hybrid 50th fest is not for every Manhattan moviegoer. Half of New York City adults are not yet vaccinated. The Walter Reade Theater on West 65th is following all guidelines on safe seating, while the MoMA screens on West 53rd remain dark. At this writing, Manhattan moviegoing is transitioning—gradually starting to shed one complete year of viewing movies all-at-home, all-the-time. Press screenings of feature films ended in theaters last March 13th and haven’t resumed. Your critic watched everything available in the 50th ND/NF a foot away from an IMac…a tepid substitute for the tenth row back from a silver screen.

Thus it may not feel surprising that the films that beckoned most vividly to this viewer were not intimate indoor dramas of conflict—haven’t we all had enough of those this past year?—but more primal, outdoor tales. At least three features and one short were infused with one fundamental pillar of ND/NF over the decades—native films by beginners in far flung lands, often unpacking stories of people living against, and with, slim odds.

Let’s call this Survival Cinema. It’s often been a new director’s best calling card in a first or second film, signaling both an intimate awareness of the land and a commitment to its indigenous communities, however accessible or remote they may be. Today’s indie startups are more technically accomplished than they were in the 70s; financing is more widely sourced; screenplays are far more candid in their scripting while their subtitles are no longer shy about spelling out four and twelve letter words. Modestly budgeted films look and sound better today, even when they’re inventing new twists on timeless tales. These three features and one short will enfold you at home, but if you can catch them one day on a big screen, be assured they’ll bowl you over.

Pebbles; P.S. Vinothraj; India; 2021; 74 minutes

The tiny Tamil Nadu villages in southernmost India are surrounded by long stretches of desert and rocky landscapes as barren and cursed with drought as anything you remember from a John Ford western. The women dig deep holes in the sand, bearing water casks back to their straw huts. Food is scarce, snakes scurry across dirt roads, hunters for the daily meal blow smoke through underground warrens to drive out the rodents.

We could be viewing a movie made in the 1930s, except that writer/director Vinothraj, who watched movies working in a DVD shop in the capital city of Chennai, is so skilled with a Sony A7 camera (with CP.3 lenses), drones, and a score that could drop you off the edge of existence, you know you’re in up-to-the-moment, professional hands. The director, who studied in a theatrical troupe while making his first shorts, recently spent a year in remote Arripatti, Madurai, writing, rewriting, location scouting, casting and rehearsing this first feature, based on his sister’s unsettled life journey. In little more than an hour he’s crafted a gem that took top prize of the Tiger Competition at Rotterdam, a festival keenly attuned to films of indigenous peoples.

Pebbles is a father/son parable, taking its title from the little stones Vadu (a gifted 10-year-old, Chellapandi) collects and occasionally pops into his mouth. His father, Ganapathy (played by a veteran theater actor, Karuthhadaiyaan) is a cauldron of fury who pulls the boy out of school to accompany him to another village by bus and on foot. Ganapathy is known to all as a drunkard, and he’s a foul-mouthed, abusive, alcoholic wreck, especially when his bare feet start to bleed in the heat. His mission is to confront his wife, who’s taken refuge with her mother, and march her back home, or divorce her, or maybe kill her, and God help anyone who gets in his way.

This is a bad man marching through an unforgiving landscape, trailed by a boy who ably fills cinema’s traditional role of the silently suffering child. The premise was a staple of European neo-realism cinema almost a century ago, and it still works powerfully when all the pieces are machined into place. Karuthhadaiyaan plays dad as a cross between Klaus Kinski in his off-the-rails performances that drove Werner Herzog batty, and Delroy Lindo as the maniacal Vietnam squad member in Spike Lee’s overlooked Da Five Bloods. The counterpointing between child and adult is never more vivid than when Vadu uses a mirror shard to bounce the sun off his father’s bare back, which the annoyed farther keeps trying to brush away. It’s a child’s cry for attention and help, one of a barrage of telling details Vinothraj has embedded in their journey. Pebbles is a miniature masterwork.

Madalena; Madiano Marcheti; Brazil; 2021; 85 minutes

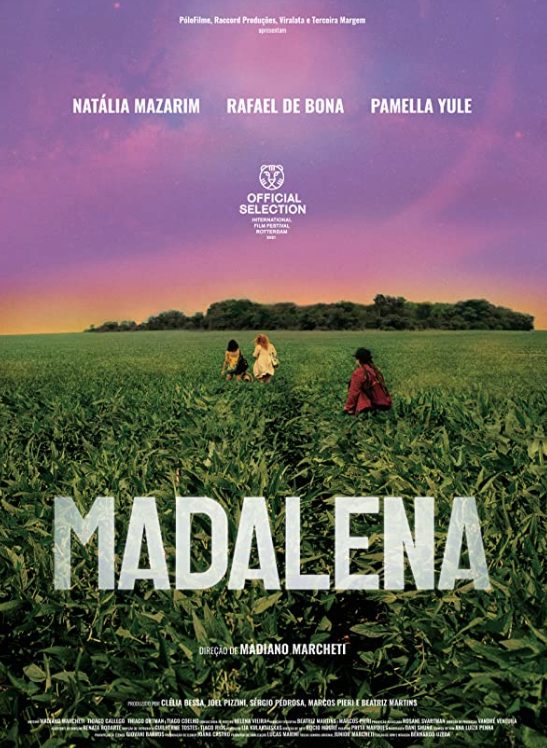

The soybean fields stretch on and on for miles, well-tended by the latest crop-spraying machines and watched by both circling drones and a flock of rheas. These long-necked, ostrich-like birds seem alert to everything going on, and it’s possible they live on a strange oasis of densely overgrown woods that conceals a fresh water lagoon. Take a look at it in the theatrical poster pictured here. It looks oddly out of place in the middle of a soybean field. Deep in the flourishing rows of soy plants, not far from the oasis, lies a lovely young woman, Madalena. She’s been brutally murdered before this disturbing and elliptical drama begins.

Marcheti’s debut feature is super-savvy and exquisitely assembled. He’s in no hurry to peel away, layer by layer, the outwardly mundane lives of the community. The guys all appear to be hired field hands, buffing up their lean bodies with steroids and revving up their noisy street bikes at night. The young women sit around their families’ tract houses that border the soy fields, filing their nails and wishing they were anywhere else. The boys and girls all hang at the local disco bar, which looks like it ought to be named Texas, and is. It’s your typical rural honky-tonk, entirely straight except for one obviously gay and forlorn couple collapsed in a corner. No one’s paying a bit of attention to them.

But then, no one seems interested in what’s happened to Madalena, either. She’s been lying dead in the soybeans for days. Laziane (Natalia Mazarim), a hostess at Texas, prowls around Madalena’s deserted home and pockets all the cash. Cristiano (Rafael de Bona), a restless field supervisor who may inherit his father’s acreage one day, discovers Madalena’s body and returns to the fields to find the corpse gone. Director Marcheti has already started a series of shots that hold on stuff a beat too long—the slightly rustling curtains in Madalena’s bedroom, the oasis in the fields, the watchful rheas.

The movie’s one source of exposition about how these random people, places and things may be linked is a car radio, which mixes local agricultural reports with breaking news of ‘another body found.’ It may dawn on you that Madalena is a doppelgänger for the vacationer who disappeared in Michelangelo Antonioni’s classic tale of alienation, L’Avventura, 60 years ago—friends searched a rocky landscape for that missing girl a while and then shrugged their shoulders and forgot about her. Was this Madalena’s fate in a community that didn’t want her there to begin with?

Marcheti has a lot more dots to connect in this measured, sleekly fashioned slow-burner. The key dot to watch for is Bianca (Pamela Yule) who makes a late but indelible appearance with friends who knew Madalena as one of their own. They mourn her a bit and then they, too, forget her, and head out for a lazy afternoon in that oasis in the soy field. A private swim in a warm dappled lagoon would be great, right? Don’t count on it.

Luzzu; Alex Camilleri; Malta; 2021; 94 minutes

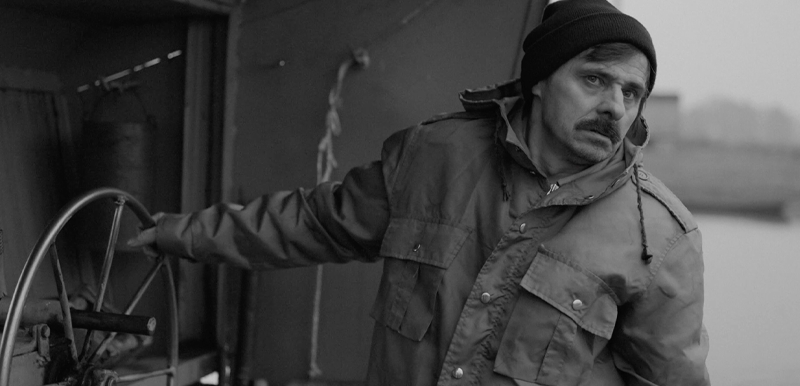

No matter how far back you reach into European cinema over the last century, you’ve never heard a trim, handsome fisherman like the guy pictured here, after a long day’s work at sea, admiringly described by the woman in his life as “smelling like a whale’s pussy.” That’s pretty startling language in a movie subtitle, and it has a jarring, contemporary intimacy.

The fishing industry in Malta has long provided its fancy restaurants with the fresh fish that feed a host of international visitors (including many film crews over the years). Maltese/American writer/director Camilleri, for his debut feature, has shrewdly updated an old, old story with more than just talk. He’s seized on the hot issue of climate change that’s gradually shrinking the legal catches in Malta’s surrounding waters. It’s the new engine that refreshes and drives this turbulent drama.

The 12-foot wooden luzzu (fishing boat) owned by Jesmark was previously owned by his father and grandfather, and is starting to leak. Expensive repairs are needed, and all his fisherman’s earnings are going to the infant he and his girlfriend Denise (Michela Farrugia) are raising. Her wages as a waitress in a local upscale restaurant won’t cover the medical specialists their troubled baby needs, so Jesmark starts to look twice at the swordfish he’s snared, and legally has to toss back into the sea. The local inspectors are vigilant with their GPS and data trackers, and the fines for selling protected fish are staggering. But Jesmark can’t help but notice how his most profitable competitors are smuggling illegal catches off their powerful trawlers, and greasing the authorities. Inexorably Jesmark is drawn into the lives of crime that are infiltrating this beautiful port city.

On paper, this is a neat, eye-opening premise. And the director has reeled in a stunning newcomer, Jesmark Scicluna, who essentially plays himself. The actor will remind you of Daniel Day-Lewis, already a legend, whose face has always communicated much more than many of his lines. The camera loves Jesmark the same way—his struggle to preserve his integrity and his family’s reputation in the fishing community, while turning to actions that will save the baby he adores, is mesmerizing. We watch him slowly adjusting the truths of his life, letting go of morality and easing into a black-market sea of shady opportunism and fast cash. At one point he’s reduced to peddling stolen gasoline by the can, to passing motorists. We can read the wheels turning in his hurt eyes, and we want to shake him by the shoulders—the surest signs we’re watching a drama that’s tragically been “inspired by true events.”

It’s a stunning performance that’s already won Scicluna a jury award in acting at Sundance. Camilleri builds his steadily absorbing story with the confidence of a veteran director and editor, layering in locals who take on their supporting roles with the ease of professionals. When a cast trusts a director and his star because they’re all of one culture, cinematic magic can happen. It’s always been that way through 50 years of New Directors/New Films, and long may it continue.

Beyond Is The Day; Damian Kocur; Poland; 2020; 24 minutes

Shorts grow in importance by the year, by the day. More and more find their way into festivals, and this edition of ND/NF includes two feature-length programs composed entirely of short films. Beyond Is The Day is the one that best combines a spirit of timelessness with the urgencies of present-day society. Its subject is immigration, but its real agenda is loneliness.

In his one room home that looks like a boxcar mounted on bricks, Pawel (played by Pawel B) watches the local news on his battered black-and-white television. The Polish government is cracking down on immigrants. It’s of little interest to this stoic and solitary man, for he’s the local ferryman. His only current passengers, who he transports across a wide river, are one cow plus a pup who seems grateful for the ride.

Then, without warning, Pawel pulls out Mohammad (Mohammad A Issa), who’s floundering in the water, holding a backpack high above his head. He’s trying to make it from Palestine to Germany, and is grateful for a cup of tea and a little food. Mohammad speaks English as well as Arabic, so we can understand him though Pawel can’t. But as citizens of the world often do, they communicate through photos (Pawel’s lost family), maps (Mohammad’s destination in Germany), sign language, and enough Polish and English words that roughly resemble each other. Pawel explains how his stiff leg resulted from a motorcycle accident. Mohammed listens politely. They are loners, and both seem glad for each other’s company.

When the woodman visits, trying to sell the ferryman some wood, they share a couple vodkas in fruit jars while Mohammad lies hidden in a storage box under the boxcar. Pawel knows the authorities are also prowling about, searching for immigrants. When they question him down by the river, he tells them he hasn’t seen any. When they knock on his boxcar door, he stands mute. You’ve seen scenes resembling these in scores of unforgettable World War II movies. When Mohammad decides he must get back on his journey, it takes a while for Pawel to explain the ferry doesn’t operate on Sunday.

Writer/director Kocur shoots in black and white, which lends this touching interlude in hospitality a severe historical perspective. The two leads, both non-professional, are acutely real and painfully believable. Kocur majored in German studies at Jagiellonian University in Krakow, Poland’s oldest university, founded in 1364. “In Poland,” he says, “hardly anyone is interested in short films.”

This concludes critic’s choices. Watch for Brokaw’s picks in the 20th annual Tribeca Film Festival, June 9-20.