Questlove debuts Harlem’s Summer of Soul

Senior Film Critic Kurt Brokaw explores the urban alternative to the Woodstock Festival of 1969

Summer of Soul: Ahmir Khalib Thompson: USA: 2021: 116 minutes

You won’t find a contemporary musician who doesn’t have an opinion on the impact of the original Woodstock festival in a farmer’s pasture in Bethel, New York, over a long weekend in August, 1969. (Your critic was there on business, delivering urgent album cover art to the Jefferson Airplane.) Woodstock, the 224 minute documentary, edited in part by Martin Scorsese, and its double gatefold LPs, are still cherished by many of the 400,000 rock fans who made it there and are still walking around today. But few music devotees outside New York City have even heard of the ’69 Harlem Cultural Festival, held the same summer over six weeks in Mount Morris Park (now Marcus Garvey Park), between 120th and 123rd streets in Upper Manhattan.

The significant link between these two festivals—the one artist who performed at both the nearly all-white Woodstock gathering and the nearly all-Black Harlem weekends—was Sly Stone, who’s closing in on 80 today. Sly’s jazz-funk fusion band, the Family Stone, featured a ferocious long-haired white drummer and an even longer-haired white tenor saxophonist, side by side with a Black female trumpet ace, Sly’s brother on guitar and his sister on vocals and keyboards.

Sly performed “I Want to Take You Higher” in both locations—at 4:00am on Chip Monck’s stage in Max Yasgur’s pasture, and five weeks earlier on Hal Tulchin’s New York stage, which Tulchin, a wily commercial producer having no budget for lighting, wisely faced west to catch the afternoon sun. Both performances are packed with a sweaty, escalating energy that rumbles, jolts and careens like a #4 express train barreling its way uptown. But the contexts for the song at the two festivals was worlds apart.

At Woodstock, “Higher” felt like a middle-of-the-night, tear-off-your-clothes dope anthem, sandwiched between Janis Joplin and The Who. Sly and the Family Stone were a long ways away—physically and spiritually—from Jimi Hendrix’ concluding set on Monday morning, when the vast majority of concertgoers who’d survived “three days of peace and music” had gone home, missing a conclusion that opened with Hendrix’ blazing guitar take on “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

In contrast, Thompson has astutely built this documentary, rearranging the sequencing of performances, and Stone’s “Higher” now registers as the Higher Calling it was surely intended to be. This time around you sense it’s a bricks-and-mortar street anthem that dramatically signals a profound shift in both Black music and Black culture. If, as they say, past is prelude to future, then “Black is Beautiful” in 1969 was the best known antecedent to Black Lives Matter in 2021. Sly and his band tear it apart in both locations. The difference is that in the Harlem version, thanks to enormously perceptive editing, we perceive Sly as very nearly the top act, one below the headliner. He sets the stage for Nina Simone.

How the Harlem festival formed and grew

Summer of Soul carries the subtitle (…Or, When The Revolution Could Not Be Televised), a reference to one of the Black Power movement’s best remembered slogans from the 1960s and is too long to fit on most theater marquees. The movie focuses on the annual festival that had built a neighborhood following through the summers of ’67 and ’68, largely organized and curated by Tony Lawrence, a local singer and employee of New York City’s Parks Department. Lawrence’s original idea was to bring in top gospel, soul and blues headliners—comfortably familiar artists like Stevie Wonder, Mahalia Jackson, B.B. King, the Edwin Hawkins Singers, David Ruffin, Gladys Knight and the Pips.

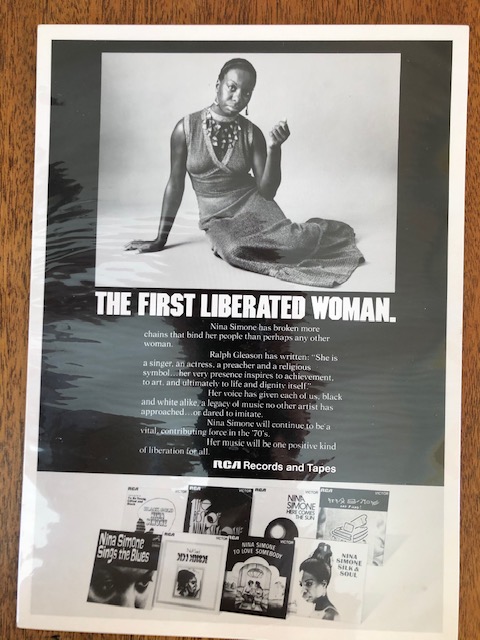

In the summer of ’69, Lawrence widened the tent. The 5th Dimension acknowledged downtown pop and the Broadway scene of Hair. Singer Abbey Lincoln and drummer Max Roach were a polished, sophisticated jazz duo. Hugh Masekala, Mongo Santamaria and Ray Barretto brought complex South African, Cuban and Puerto Rican instrumentals with their loyal constituencies. Sly and the Family Stone was a mixed-race ensemble who some folks along 125th Street at the time might have grumbled was better suited to Woodstock—period. And Miss Simone was, well, a temperamental goddess not to be tampered with by anyone. (Take it from the guy who made her ads at RCA Records, including the one pictured, which she approved.) But Lawrence was an igniter and energizer, a firebrand MC—his dream was to broaden the music base that summer, to film a concert that would open doors for national, even international tours that world promote Black music to the world.

Lawrence never got his concerts beyond Harlem and his footage never got to the big screen. For decades the cans of high definition, two-inch tape, which Tulchin had shot in ’69 with bulky stand-up studio cameras, lay dormant in his Westchester basement. The producer longed for anyone to put a movie together he’d call Harlem Festival and position as the Black Woodstock. (This writer shot commercials with Tulchin for four years during the 1960s and knew him well.) The logical backer might have been Maxwell House coffee, the events’ one commercial marketer and sponsor. But no one called…no one until Ahmir Khalib Thompson, better known as Questlove, the drummer and joint frontman for the Roots, who directed the feature. And after it won the 2021 Sundance Festival Grand Jury Prize for documentary, Searchlight Pictures (formerly Fox Searchlight)bought it for wide distribution.

More may wonder why Summer of Soul didn’t also open the 20th anniversary of New York City’s Tribeca Festival June 9th, rather than Lin-Manuel Miranda’s In The Heights. Miranda himself makes a quick appearance in Questlove’s doc, marveling at a series of outdoor shows that took place 11 years before he was born.

Thompson defines himself as “drummer, college professor and storyteller,” and was among the first eyes in half a century to view the concerts that were close to being tossed out of Tulchin’s basement. He immediately sensed their importance, then as now, in similar eras of national racial strife. He asks: “If a brilliant, monumental festival falls in a forest, and no one’s around to hear it, did it actually even happen?” It’s Thompson’s debut feature, to be followed by his book, Music Is History, releasing this October, and if ever there was a right movie by the right director at the right moment, this is the one.

Performances of a Lifetime

Many of the numbers that Tulchin’s cameras captured are indelible, none more than when Mahalia Jackson starts “Precious Lord, Take My Hand,” which she’d sung at the funeral of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. a year earlier. Miss Jackson, perhaps feeling a weakening heart, begins to falter and reaches out for help to the closest person on stage, Mavis Staples. Mavis’ voice at 30 was at peak power, and she easily takes the lead. But her clear contralto somehow empowers and emboldens Jackson, and the two women join in an unrehearsed call-and-response that’s a spiritual marker for the ages.

And then there’s Nina Simone. She starts her set nearly breaking the keys on the piano with “Backlash Blues.” It’s a volcanic protest anthem against “second class houses and second class schools,” written for her by the preeminent poet Langston Hughes, in which he urges Nina to”keep on working ’til they open up the door…make sure you tell them exactly where it’s at, so they’ll have no place to hide.”

The key connection between Simone and director Thompson’s Summer of Soul occurs in her tribute song, “To Be Young, Gifted and Black,” dedicated to her friend Lorraine Hansberry, the first Black woman to have a play produced on Broadway, in 1968. The dots are connected right in the lyrics, and maybe they were always waiting for the right messenger—Questlove—to come along and find them: “We must begin to tell our young, there’s a world waiting for you…Yours is the quest that’s just begun.”

Summer of Soul opens in theaters and on Hulu July 2.

Editor’s Note: Film at Lincoln Center and Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts are offering a special Juneteenth celebration at Lincoln Center’s Restart Stages featuring Summer of Soul. The screening will take place Saturday, June 19, 2021 at 9:00 pm ET. The venue is offering cabaret-style pods for two people through their TodayTix app. Entries close on June 16 at 12:59 pm ET. More information about the event is available at lincolncenter.org.

Regions: New York