20th Annual Tribeca Festival June 9-20

Senior Film Critic Kurt Brokaw salutes top films in a festival reenergized once again by uncertainty and hope

In the spring of 2002, Jane Rosenthal, Craig Hatkoff and Robert De Niro launched the first Tribeca Film Festival to help revitalize a hurting New York City and an economically devastated downtown neighborhood. They knew it wouldn’t be easy selling the concept of taking in a movie and dropping some money in the restaurants and retail shops south of 14th Street. Many had stayed open or managed to reopen, barely six months after 9/11. Some days on some blocks, it took a stiff wind just to dispel the lingering traces of smoke. The last thing Soho and Tribeca residents expected to see was a film festival that promised something for everyone.

Tribeca invented right and left—street fairs, outdoor movies on piers, audience awards, a volunteer army of eager interns, merchandise tables that sold shoulder bags like the one this viewer still carries. A bruised and dazed city began to pay attention. The heavy lifters—like Marty Scorsese who curated classics like Viva Zapata along with his fave NYC films, and American Express—the marketer that cut the biggest checks—moved mountains in days. Filmmakers worldwide quickly offered up their shorts, docs and narrative features, in part hoping to attract a distributor. Suddenly 150 movies were showing all through downtown Manhattan, and people came out and lined up. TFF started an annual run that’s never stopped growing.

The spring of 2021 is different, but not different. Rosenthal and De Niro have continued both their Tribeca sponsorship and their producer/actor partnership (most recently on The Irishman). The Tribeca Film Festival has become the Tribeca Festival, not because there are fewer movies (66 this year), but because the sum of a festival today is more moving parts— virtual and augmented reality, games, television shows, season premieres, a Juneteenth survey of Black cinema, brand storytelling, stand-up comedy specials, podcasts and art displays in unoccupied storefronts. This time around AT&T cut the heftiest checks. This time a pandemic has killed over 33,000 New York City residents in barely over a year, and local moviegoers, most still masked up arriving on foot and on mass transit, are of two minds: Some are getting out for in-person viewing, others find it easier or safer viewing online. (The New York Times Summer Movie section May 30 didn’t do much to encourage theater visits with a full-page article ominously headlined “Now Playing Everywhere: High Anxiety.”) This Tribeca Fest offered it both ways.

Free live showings were held on the Brooklyn Commons, at the Battery, on Pier 76, in Hudson Yards public square, on the roof of AT&T and in six large city parks. On the other hand, if you had $25,000 sitting around, you could have purchased a 20th Anniversary Founder’s Package with VIP no-waiting-in-lines access to all in-person screenings/events and immersive exhibits. (Far more economical packages were available online for international narrative features, Q&As, documentaries, viewpoint selections, shorts, online premiers, episodic work, and virtual arcade experiences.) Put another way, you could have spent nothing, a little or a small fortune.

For this viewer, the two most vivid stories from Tribeca’s global community in 2021 are a narrative musical and a documentary. Both are told by storytellers, literally and figuratively, and each explores aspects of the Dominican Republic—its fervid passions updated from a famed Broadway musical, and the stark realities of living in the Dominican Republic today, with its neighboring people of Haiti. Seen back to back, a red carpet first night New York premiere and its infinitely smaller, independent counterpart expand the width and breadth of storytelling at its best.

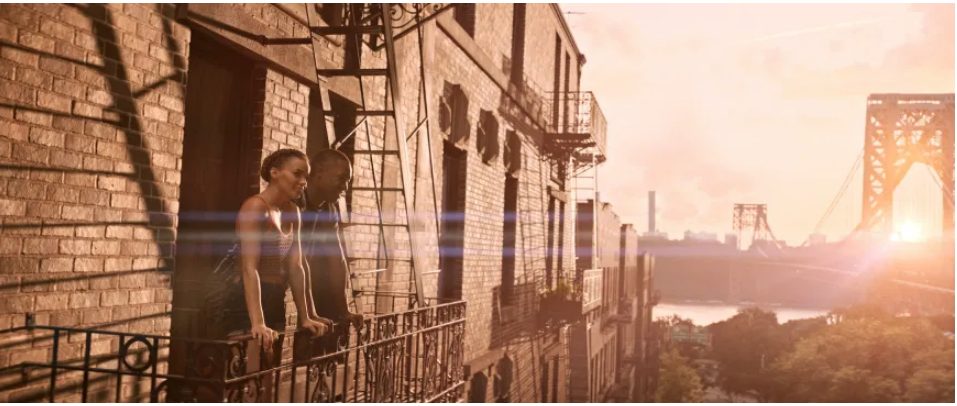

In The Heights; Jon M. Chu; United States; 2020; 143 minutes

You’ve got your vaccinations, now head out to the largest movie screen in our neighborhood—IMAX would be the one to scurry to, by foot, bike or subway— and get a booster shot for your soul. Ladies and gentlemen, clap your hands together and warmly welcome the 55 million dollar Warner Brothers’ Super Musical!

It’s true: Lin-Manual Miranda’s Broadway hit has become the most pumped-up, soul-driven Opening Night in 20 years of Tribeca Film Festivals. It darn near overwhelms this newly styled Tribeca Festival in which television pilots, intimate little podcasts and immersive, interactive viewings are all the rage. The director of Crazy Rich Asians once again feels like a madman lost in the old joys of scissors and soundboards, blasting out torrents of colorful imagery and wall-shaking sonic stun. The release of In the Heights this summer is hoping to jolt moviegoers loose from a year of hunkered-down, masked-up isolation.

The picture works. Oh, does In the Heights work, because you haven’t been this embraced and engulfed in a New York movie that works so hard, so long, to entertain and enlighten you, in what seems forever. You won’t spot a mask in the entire 143 minutes! There’s hardly a mobile device in sight! Whoa now—Chu’s movie sings and dances its way into and through a BLACKOUT in the middle of a July heat wave so godawful (106 degrees), it’d melt all the Tar Beaches citywide. And with barely a cellphone, let alone a street corner pay phone, in sight. How’s that work?

Time frame and relevant issues (the movie and the play)

Just when is this movie taking place? In the summer of ’03, when the city endured a major blackout? (Possibly, as its Broadway counterpart didn’t start previews until ‘08, and the libretto doesn’t specify the year of its boiling hot July 4th.) In the summer of ’65, when Manhattan had its whopper blackout? (Doubtful, as mobiles weren’t around and Miranda didn’t begin writing In the Heights until his college years at Wesleyan in the ‘80s, though he finished it in ’99 as devices began appearing.) Maybe this summer or a future summer? (Most likely, as Broadway librettist and co-screenwriter Quiara Alegria Hudes has stated “we decided to make it contemporary.”)

Make no mistake, In the Heights takes place in an invented Latinx neighborhood in which Covid, homelessness, and turf wars are not distractions because they’re somewhere way off screen, like 99% of all mobile phones. The one sharp-elbows standoff, with an initial whiff of hostility, is between the Mister Softee driver and Piaguero (played by Miranda himself) who pushes the shaved ice cart, and even these two street vendors come to grudgingly acknowledge each other. The film’s last magical moment of one particular couple cuddling one particular daughter also suggests we’re in a blended filmic past, present and future. In its kinder, gentler revelations, and there are many, In the Heights may not feel that distant to parents from Sesame Street.

On the other hand, the screen’s “contemporary” version, to its credit, adds relevant issues not seen on stage. There’s a Dreamers’ street rally led by Maria Hinojosa, NPR’s anchor of Latino USA…the neighborhood’s salon head waking up with her female partner in the movie’s break-of-dawn opening…Vanessa’s (Melissa Barrera) frustration downtown, applying for an apartment she can’t financially qualify for…a documentation issue that Hudes calls “a litmus test of Americanness we had to address.” There’s also a new reason for student Nina Rosario (Leslie Grace) dropping out of Stanford University—not because she can’t live without her boyfriend, Benny, the car service dispatcher (Corey Hawkins), but because she’s suffered the humiliation of being falsely accused of stealing her upscale roommate’s jewelry. These touchy, urgent topics lends a newsy immediacy to the engine driving the narrative between songs.

1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 show stopping numbers to write home about

The greatest Hollywood musicals of the last century were designed to pull Depression-era, wartime and post-war audiences out of their hard times and gloom. Each provided a signature production number that predominantly white audiences have remembered all their lives—Gene Kelly getting joyously soaked in Singin’ in the Rain or dancing with an animated mouse in Anchors Away; Fred Astaire prancing across the ceiling in Royal Wedding or matching Ginger Rogers step for step for step through Top Hat; Bob Hope and Jimmy Cagney outdoing each other as vaudeville hoofers in The Seven Little Foys.

Compare that with at least seven knock-your-socks-off numbers that Chu and choreographer Christopher Scott have staged in and around Audubon Avenue and 175th, at nearby Highbridge Pool, in a hair salon, a salsa club, vintage subway cars, an enclosed back area between buildings, and (last and least expected) a gravity-defying sequence with Nina and Benny swooning about, up and down the outer walls of his building, just down the block from the majestic George Washington Bridge. Every number is a showstopper led by a multi-ethnic cast bursting with agility, swagger and boundless energy. Any inventive tagger who sees Warner Bros.’ poster on the side of a bus with its theme line, The Time Has Come, may be tempted to shorten it to It’s About Time.

Usnavi’s Framing Story

Like Joel Grey’s commanding master of ceremonies in Cabaret and Paul Newman’s droll stage manager in Our Town, 29-year-old Anthony Ramos (Usnavi) anchors the movie. Usnavi serves as host and storyteller. Manuel, now 41, originated the role on Broadway at about the same age. Usnavi spins his tale from a white sand beach in the DR, talking to a handful of adoring kids, both introducing and reacting to all that takes place in New York. It’s a charming device that works throughout the movie, keeping the young bodega manager a trusted narrator. Society’s promises vs. the daunting realities of Usnavi’s block stand in sharper contrast today on screen than they did a decade ago on stage. Gentrification and rising rents are the ever-increasing enemies now, forcing the nearby hair salon to relocate up to the Bronx, while a big winning lottery ticket—still the city’s ultimate everyday hope to millions— is once again bought in his store by someone close by.

Ah, but who? This is the most tantalizing element that Miranda and Hudes embed in their Heights. Abuela (Olga Merediz), the block’s favorite grandmother, buys a ticket every day. Kevin Rosario (Jimmy Smits), who’s just brokered his car service to pay his daughter’s college tuition, drops a twenty on his “dollar and a dream.” Daniela, Carla and Cuca (Daphne Rubin-Vega, Stephanie Beatriz, Dascha Polanco), the salon’s about-to-be displaced ladies, could sure use a windfall. Neither Miranda’s shaved ice guy nor his arch competitor on the ice cream truck (Christopher Jackson) are making a bundle on the street. One somber truth that the most ebullient, Busby Berkeley-styled human pinwheels in the municipal swimming pool can’t conceal is that some in this community, in the richest city in the world, are barely getting along. Then there’s the blackout. Then Abuela goes to sleep and doesn’t wake up.

Your critic wouldn’t have pulled you this far through a lead review without suggesting that Ms. Merediz, who created Abuela onstage and didn’t quite win a supporting actress Tony, has bettered her chances of winning in next spring’s Oscar competition. (She’s said of playing Abuela, “I can bring my family, my past, my Cuban-ness, my Latina experience, my experience as Olga.”) Wherever those awards are held, the venue isn’t likely to outdo the sheer magnificence of the United Palace, the 91-year-old neoclassic showplace on Broadway at 175th street, in the heart of Washington Heights, where Chu’s delicious confection had its New York premiere. And hopefully Ms. Merediz, whose undying wish in the play and now in the movie, has been to “make an invisible people visible,” will see her patience and faith rewarded.

Stateless; Michèle Stephenson; United States/Canada/Dominican Republic/Haiti; 2020; 96 minutes

Short history lesson: The Dominican Republic and Haiti share the island of Hispaniola. From 1937 on, the titles of Stateless tell us that one regime after another has subjugated and eradicated thousands of Haitians living in the DR, as well as lighter-skinned Dominicans. In 2013 the citizenship of Dominicans of Haitian descent were revoked—essentially rendering them stateless—leaving over 200,000 children, women and men without nationality, identity or a homeland.

One is Rosa Iris Diendomi-Alvarez, a practicing attorney for three years and a community activist/organizer for 15 years. A devoted single mother of two young Black children, she’s the focal point as well as the narrator of this essential documentary. Like Anthony Ramos in In The Heights, she weaves a story in and out of her real-life events, except this time the story becomes an early warning signal of all she’s up against.

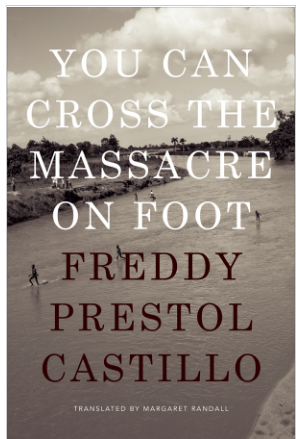

The story becomes the frame that infuses the documentary with an ominous magical realism. Examine the cover of its novelistic diary: You Can Cross the Massacre on Foot (Duke University Press, 2019) written by Freddy Prestol Castillo, a judge who presided over the border in 1937 when tens of thousands of Haitians on the Dominican side were killed by the Trujillo dictatorship. This is the inspiration for director Stephenson’s creation of a story that Rosa narrates as a voice-over throughout the documentary. The story is of a young girl, Moraine, who watches her mother die in the Massacre River, and can find no hiding place in the surrounding sugarcane. Moraine tries fleeing across the island to safety, and doesn’t make it. The story is a frightening metaphor for all Rosa feels up against as an adult.

Rosa spends her days desperately advocating for the poor in her region, checking to see they have their birth certificates as the government of 64-year-old Danilo Medina relentlessly seals borders and begins to scuttle “illegal settlements.” We watch as one Haitian is turned down for citizenship under the DR’s National Regularization Plan, being told “you don’t speak Spanish clearly.” Rosa’s own cousin finds it impossible to renew his passport and “feels like a foreigner in my own country.” She tries to explain to her daughter that the girl has no nationality—“you’re here but officially you don’t exist.”

As Rosa makes her way through the sugarcane communities, we observe that this fearless attorney is known, respected and trusted by the people she grew up with. (Her mother was 5th generation Haitian-Dominican, her father was a Haitian migrant.) When Rosa decides to run for election, with virtually no budget, against Medina’s massive war chest, the parallels with the story of young Moraine take on an eerie reality. In the Heights was a day-by-day countdown toward a non-violent New York City blackout in (maybe) 2021, but Stateless is a race-against-the-clock toward an election Rosa has almost zero chance of winning in 2016.*

Conservative women in the privileged DR community, who back the building of a wall separating the two peoples, label Rosa as an“ominous, obscene, anti-Dominican woman.” Hate mail warns her to guard her daughter “so you don’t find her one day with her mouth full of ants.” A supportive local radio host and journalist is shot dead. On election day, the movie suggests that many DR citizens were paid 50 to 100 pesos at the polls to cast their votes for Medina, who was easily reelected.

Stateless’ writer/producer/director Michèle Stephenson, who identifies as a Black Latina with Haitian and Latinx roots, has assembled a taut, scarifying portrait of a Haitian population under siege. Her documentary has a first-rate list of financial backers including The National Film Board of Canada, Chicken & Egg productions, and the film institutes of both Sundance and Tribeca. Stateless is the mirror opposite of the sunny, feel-good In the Heights, but once you’ve treated yourself to the former, you might want to seek out the latter. (It will have its broadcast premiere on PBS’ POV on July 19.) Kudos to Tribeca for honoring both.

*In August of last year, former president Medina was defeated in a re-election bid by a local businessman/politician. Don’t get your hopes up. One source reports that the new DR president’s security detail was advised by former New York City mayor Rudy Giuliani.

Coded; Ryan White; USA; 2021; 29 minutes

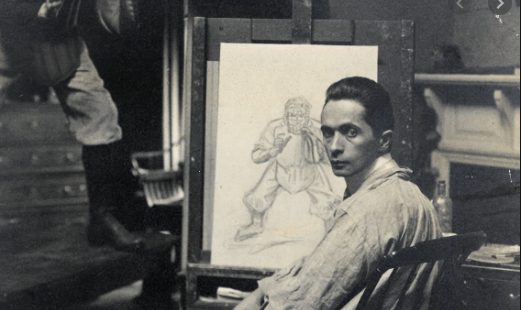

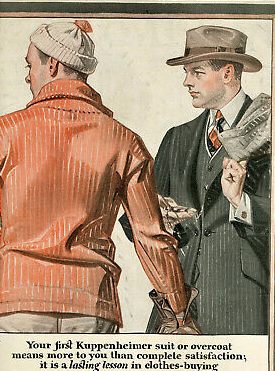

There were a lot of Don Drapers— classy Mad Men in Madison Avenue advertising agencies in the second half of the 20th century—but few were openly gay. The classiest gay Mad Man in earlier eras—certainly from the turn of the century through World War II—was the illustrator J. C. Leyendecker (1874-1951). The name may be unknown, but you’re surely familiar with some of the leading marketers and magazines he painted for: Arrow shirts, Gillette, Ivory Soap, Kellogg’s, Kuppenheimer suits, Collier’s, The Saturday Evening Post. Not to mention Procter & Gamble, a partner in the making of this exquisite tribute film.

Though most of Leyendecker’s fashion images are upper-crust Park Avenue, most of his model’s poses look as innocent as freshly driven snow. But more than a few were embedded with subtle, semiotic signals other gay men instantly recognized. The German-American illustrator was educated at both the Chicago Art Institute and in Paris, where he studied great poster artists like Lautrec and Mocha. When Leyendecker returned to Manhattan, he ended up hiring movie-stars-to-be including John Barrymore, Brian Donlevy and Fredric March as models. In Charles Beach he found not just his perfect Arrow shirt and collar model, but his lifetime partner. Beach stayed known to the outside world as the painter’s secretary and business manager, but the two men shared a secluded, luxurious life even after America’s post-War return-to-normalcy doomed their cosmopolitan dream weaving. All told, Leyendecker painted 322 Post covers over a half century, virtually the same number created by his friend and admirer, Norman Rockwell.

Ryan White crafts this biography with elan, delighting in deft animation directed by Danny Madden, with Neil Patrick Harris expertly voicing J.C.’s diaries. There are three talking heads you’d love to hear more from—Calvin Klein’s Black transgender model, Jari Jones, art historian Jennifer Greenhill, and author Judy Goffman Cutler. They braid the strands of what could easily be woven into a feature-length gay culture biopic of significance.

Ms. Cutler, the author of J.C. Leyendecker: American Imagist, has the singular sensational moment here. For some time, she tells us, she owned the Ivory Soap painting shown below, without ever noticing one detail. Whoopi Goldberg, her guest one night, spotted it right away. You may need a magnifying glass to closely examine the covered area directly under the tie on the model’s bathrobe. It’s an example of J.C.’s mischief, and it’s a dilly.

The Queen of Basketball; Ben Proudfoot; USA; 2021; 22 minutes

In Toni Morrison: The Pieces I Am, cited in The Independent‘s 2019 review as “2019’s must-see biography,” the late Nobel Prize winner narrated her own life for much of two hours. You couldn’t take your eyes off her because she wouldn’t take her eyes off you. Ms. Morrison left no doubt how she’d replaced the “white gaze” of too many novelists with her own Black gaze. She was, as the review noted, “infectious, disarming, mischievous…with a big, hearty, approving, empathetic laugh.”

Lightning strikes again with Ben Lightfoot’s mini-biopic on Lusia “Lucy” Harris, a pioneer and a champion in the world of women’s basketball. At 66 she’s a commanding presence, and like Ms. Morrison she speaks directly to the camera and thus direct to you. One can’t help but settle back and relax into learning how a 6’3” Mississippi teenager led her Greenwood team to a state tournament in Jackson.

Her nickname then was “long ’n tall, and that’s all,” but none of her classmates had a clue what was simmering and brewing. In her first year at Delta State University as their center, Harris led DSU’s women’s team to 16 victories, losing only twice. In the next years Delta State beat Immaculata university, once, then twice, winning the national tournament title. Harris was MVP and piled up a college record of nearly 3,000 points and over 1,500 rebounds. She helped her team win gold and silver medals in the ’75 Pan American Games and Summer Olympics Games.

Harris became the second woman ever drafted by an NBA team (Utah Jazz), but her first pregnancy prevented her from trying out. In ’92 she was the first African American woman inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame. She is also a member of the Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame and International Woman’s Sports Hall of Fame.

Director Proudfoot intercuts a treasure trove of footage of Harris—who’s invariably taller than her teammates as well as her opponents—culled from 16,000 feet of film and 10,000 film negatives in the archives of Delta State U. There’s a busy, endlessly inventive music score by Nicholas Jacobson-Larson that races pulses as adroitly as it wells up tear ducts. And Lucy Harris? Whether she’s basking in the incredible prowess of her work on the courts, or telling us, haltingly, with more than a touch of regret, that “there was no WNBA when I came along, it didn’t exist,” she’s the talking head sweetheart of this 20th anniversary festival.

This concludes critic’s choices. Watch for Brokaw’s picks in the 59th New York Film Festival, September 24-October 9.

Regions: New York City