Making Dreams Real

The Art of Creating Virtual Reality, an Interview with Pierre "Pyaré" Friquet and Ando Shah

French digital artist Pierre “Pyaré” Friquet and his filming partner Ando Shah were wrapping up their first narrative virtual reality (VR) narrative film project Jet Lag in Mumbai when they felt the high-rise building beneath their feet start to tremble. It was 2014, and they were 2000 miles away from the Nepal earthquake epicenter.

They got on a flight—the only two passengers going into Nepal as everyone fled — and shot their first VR documentary Vibration. Shah’s dream before their departure inspired the opening narration of the documentary, “I had had a dream, but when I woke up only fragments remained in my accessible mind. As the fragments faded, I was left only with the conviction that I had to go to Nepal.”

This was the beginning of Friquet’s journey of becoming a “sorcerer’s apprentice” where he began to mix societal themes with his own personal experiences to create new collective experiences through VR.

Six years later, Friquet premiered his first underwater VR experience Spaced Out at the 2020 Sundance Film Festival. The film used the first waterproof VR headset developed by Shah’s company Ballast Technology to give viewers a completely immersive experience. This project was featured in the New Frontier exhibition and was by far his biggest success.

“People see VR as a business, a new industry. I’d say that VR is art,” Friquet said. “People always interview producers, about hardware, about software ecosystems, and business modules. We don’t talk enough with artists.”

Rashin Fahandej, artist in residence at Boston Mayor’s office, who also teaches interactive and emerging media at Emerson College, expressed similar sentiment.

“It’s only been a few years [since] immersive storytelling [become] quite established at film festivals,” Fahandej said. “It gives [artists] a new language, vocabulary, and tools, to say a story differently.”

Friquet didn’t originally intend to work within this new medium of storytelling. After graduating from the Film and Television Institute of India in 2009, he was one of the few international students who got to study in its directing program. As he started off his career, he was very frustrated by the film industry that he was going into.

“[The things that they were making] was not the spirit of film, spirit of cinema, spirit of independent cinema. [The spirit] doesn’t come from the material, the equipment, or the form itself,” Friquet said. “Representing reality is beyond the 35-millimeter film camera.”

He found problems in the linearity of cinematic storytelling. Friquet wanted to tell stories in a vertical, holistic way. Something akin to lucid dreaming, where a trained dreamer knows they are asleep and can manipulate how actions unfold around them. This was the experience he wanted to share with others.

Inspiration hit him after he came across CNN’s 360° video coverage of the 2010 Haiti earthquake. He called it his “heroic moment” and decided that he needed to tell stories via VR. However, 360° cameras and VR were still new technologies that only appealed to a niche audience. Few corporations were investing in the technology. As a man with only ideas, he would have to find other resources to fulfill his vision.

Friquet would find help in 2014, the same year Facebook acquired VR headset maker Oculus, when he was introduced to Ando Shahthrough a mutual friend in India. At the time Shah was self-employed after quitting his job as a hardware engineer in Silicon Valley. “I was working as a professional photographer at the time, so I had kind of built the skill of being able to tell stories visually, but not so much in film,” Shah said. “My first impression of Friquet stuck around, I always thought he was a bit crazy and a bit of a visionary.”

Shah brought his expertise in VR and camera design and started to record in 360° by putting a bunch of Go-Pros together to film from different angles. Shah said that sync filming was probably the biggest issue, and Friquet recalled Shah only took on this project because he created a system that allowed six cameras to film at the same time. During post-production, they had to put all the optics together as well as taking out stitching lines while editing the footage. This allowed each frame to match each other’s lighting and create seamless scenes shot on different cameras without overlapping images.

They used the prototype for their first 360° project, Jet Lag, as well as the documentary, Vibration, which both came out in 2015.

Jet Lag came out of the end of Friquet’s long distance relationship. He was left with text messages, emails, photos, and other digital ephemera, but he didn’t know what to do with them or the sense of longing they produced in him. He would use that feeling to create a story of two women navigating the uncertain terrain of a suddenly-long-distance relationship using an Indian classical dance. Friquet abandoned the long takes in this film and choreographed the actors so that he didn’t need to edit out shots.

“You choreograph the actor’s performance according to the camera, creating close-ups, and long shots, but not by cutting or changing the camera orientations, [instead] by having the actors going up and down,” Friquet explained. “I was more comfortable to work that way because I felt this is a way we can just look around and it’s just more useful.”

Friquet would also abandon the traditional way of writing a script for this project since he believed it would also impose linear restrictions on a story. Instead he used a spreadsheet of different columns to suggest different ideas and shots going vertically. “There was a lot of unlearning to be made, [to] deconstruct the film-making process,” Friquet said. “[The stories] also came from inside me, so my projects are always personal.”

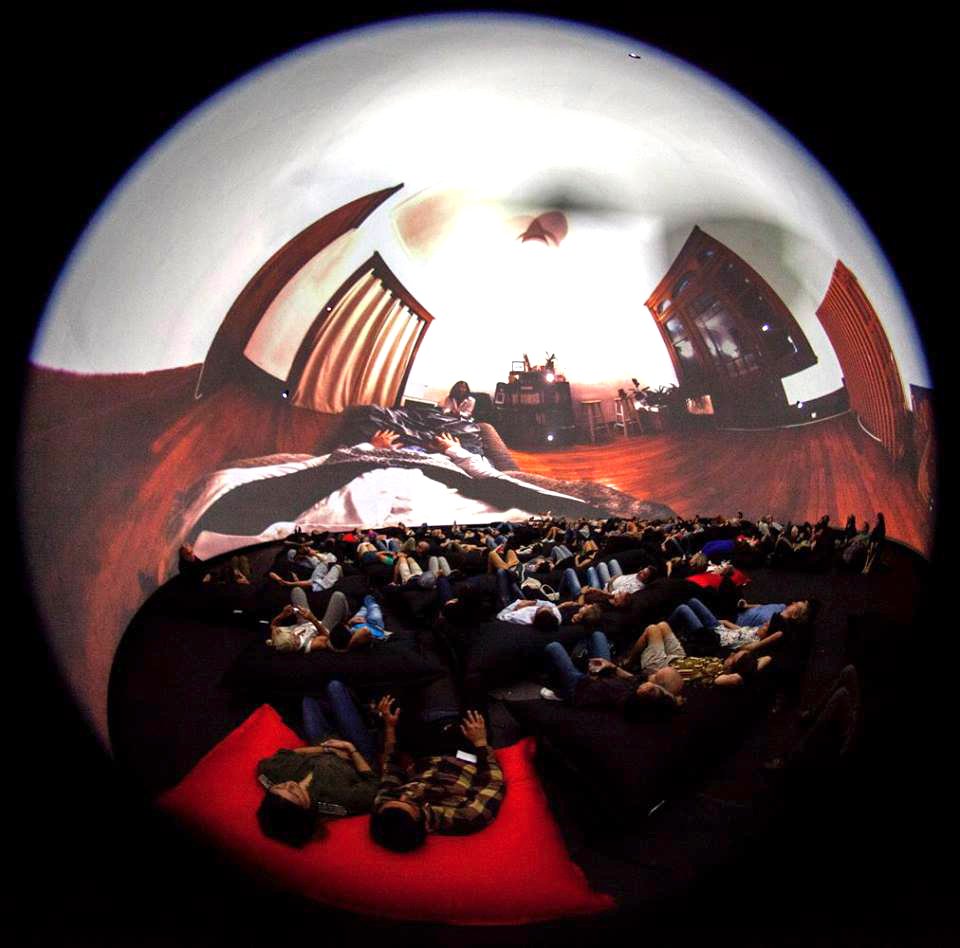

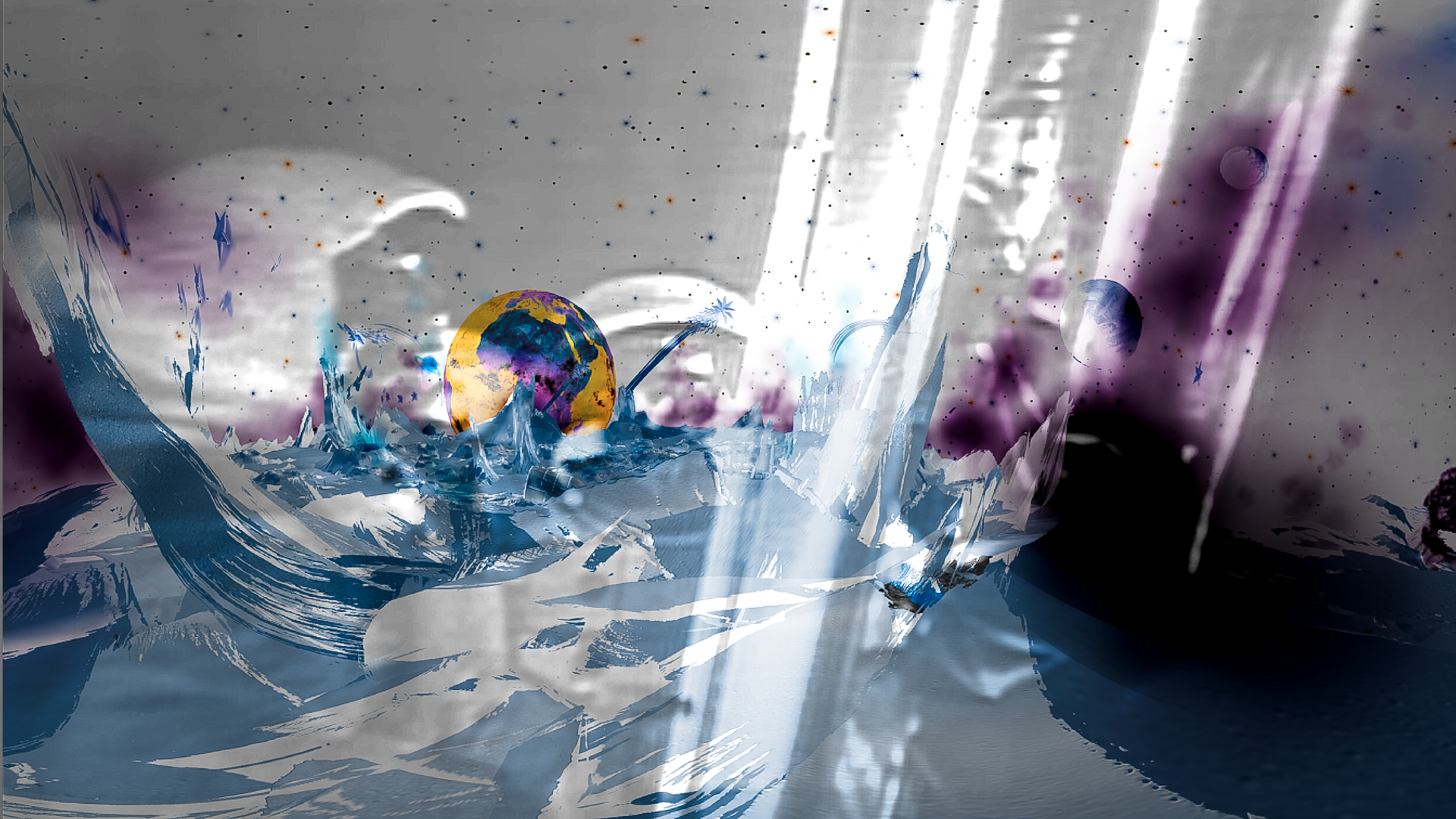

After their first two films were successful, Friquet and Shah teamed up to make Patterns, a VR experience series narrating a hypnosis session on why the main character feels possessed through his memories, his imagination, and a recurring nightmare. Friquet adopted this idea from horror-fiction author H.P. Lovecraft’s universe, but also incorporated his own family’s true stories.

To create horror effects they used ferromagnetic liquids and a micro lens for the shooting, giving audiences an almost trypophobic feeling by looking at the patterns of the liquid. In order to help the audience travel through different mediums, Shah said they scanned the interior of a huge Victorian house and projected it onto a domed theater. Friquet and Shah would make two more versions of this project to reflect the advance in VR technology.

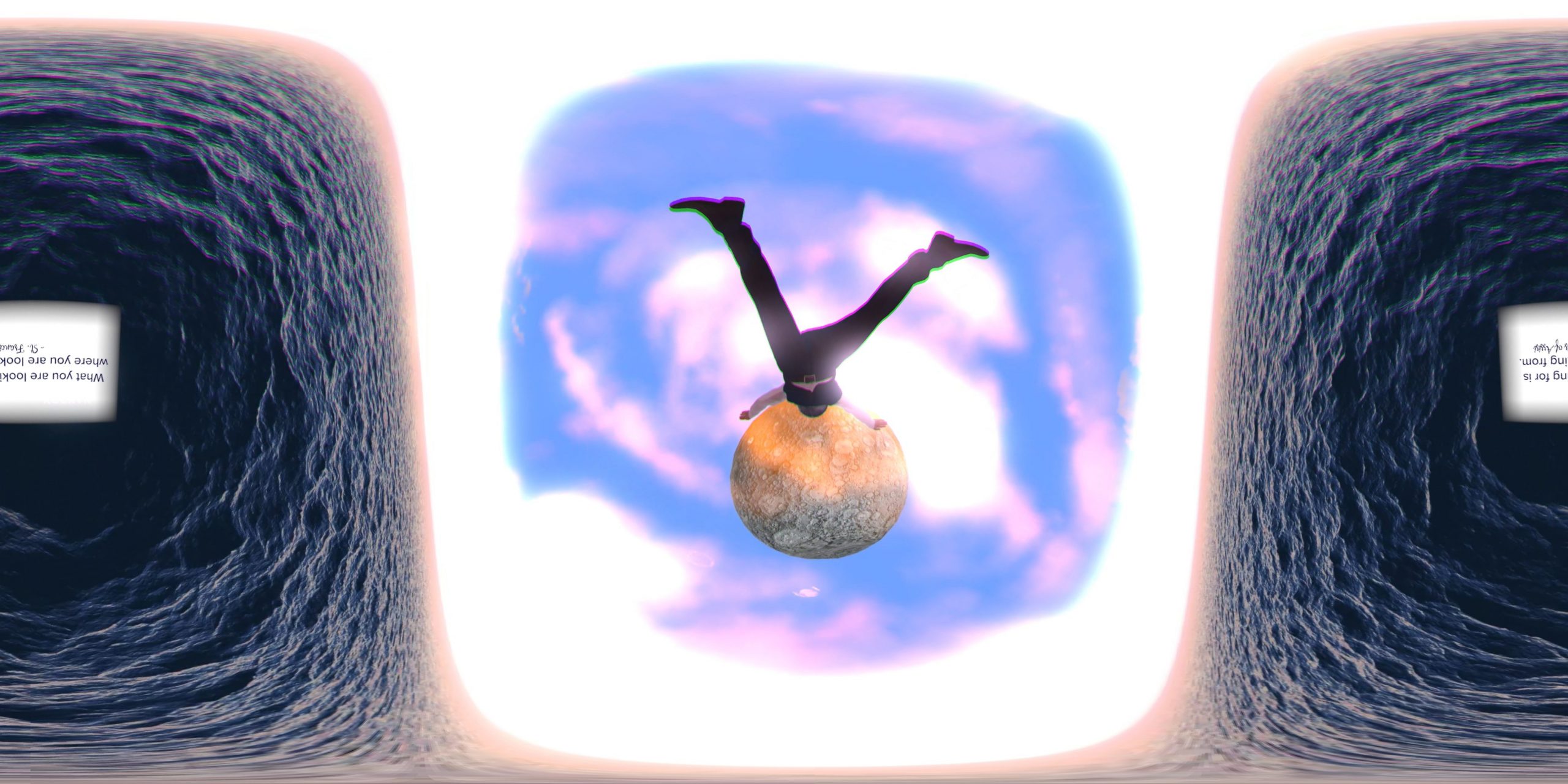

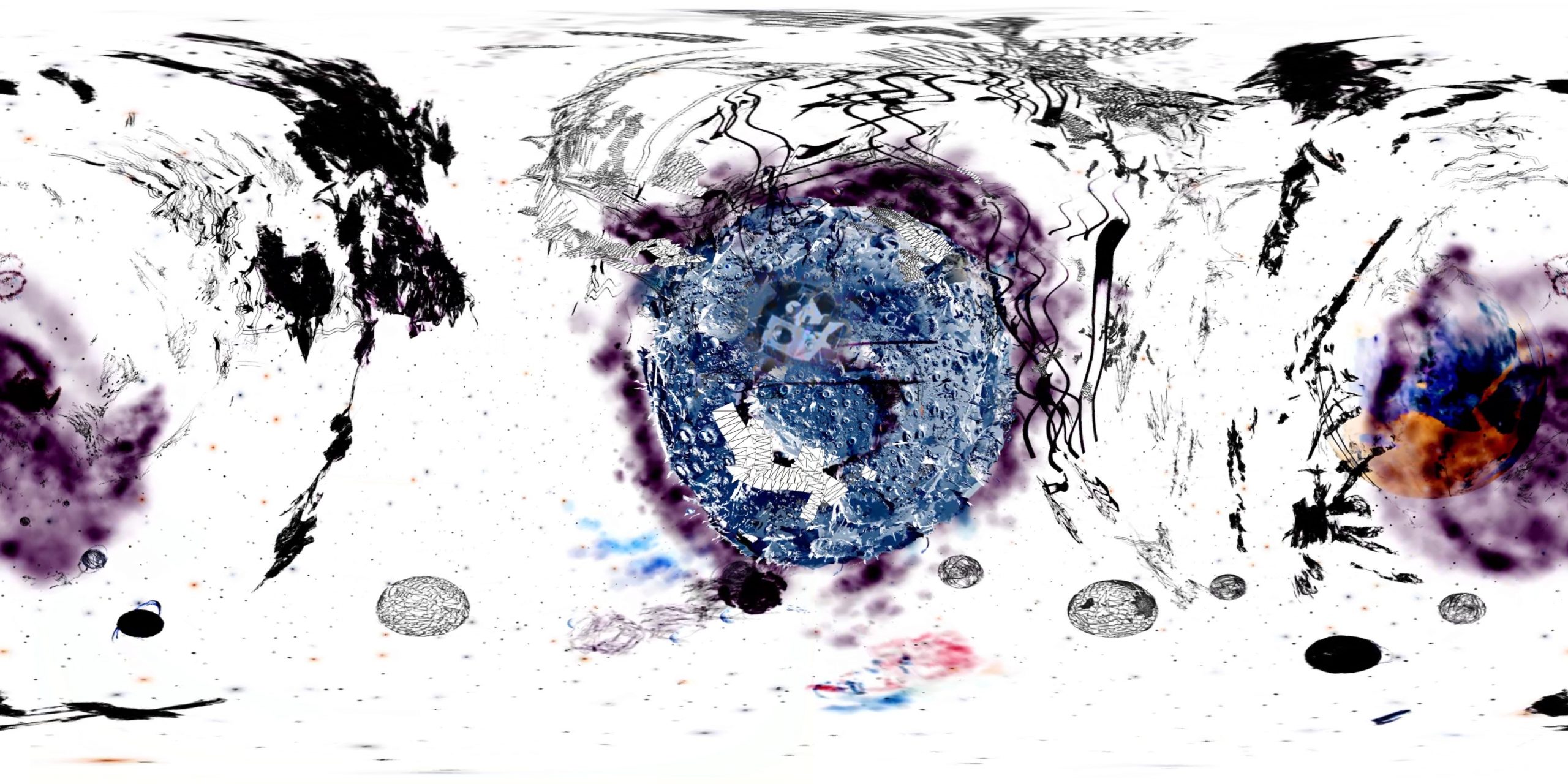

With Shah’s new technology, Friquet was able to make Spaced Out, an underwater VR experience that “transports the visitors from Earth to the moon, from water to space and from the first to the third person leaving the body behind.” Users are submerged in a swimming pool while breathing from a snorkel, where the limitations of gravity and physical space are lessened. Once in this weightless, direction-less environment, the VR headset takes them on a trip to the moon. Shah explained that the lack of gravity while floating in water seems to interrupt the vestibular system or the inner ear’s ability to sense orientation, acceleration and velocity, thus users feel almost no motion sickness.

For Friquet, the goal of this project was quite simple: he wanted his users’ bodies to generate their own experiences by going through different elements and the sensation of weightlessness.

“I was interested in using VR in a very more ancestral way, so putting people in water makes them connect with just themselves,” he said. “I wanted to explore the story of discovering something for the first time, so going to the moon for the first time with the sound of the Apollo 11 mission. I also have images from films like ‘A Trip to The Moon’ by George Méliès.”

For emerging digital artist Rashin Fahandej, artist in residence at the Boston Mayor’s Office, who met Friquet at Sundance, said this is a perfect example of matching the right technology to tell the right story.

“This piece is a very clever use of VR,” Fahandej said. “A big portion of the challenge with VR is that there are limitations in movements because you get nauseous, [but] you don’t get motion sick with this piece.”

Fahandej pointed out that not all stories fit into virtual reality because it was a completely different language compared to other forms of digital storytelling.

“You need to ask yourself why this story needs to be told with this tool and this technology. Immersive installation has a very different intention and goal than a flat-screen,” Fahandej said. “We talk about audience, not as audiences [but] as visitors, we don’t talk about storytelling, we mostly talk about word-building.”

For Friquet, VR was the “ultimate poetic machine.” Creators needed to create a metaphor to fully represent something to their audiences, especially for films, writing, or painting. But for VR, the viewers were already in the space, and there’s no need to use actual language to describe anything.

“In films, you cannot shoot hunger. You have to create association by editing— you have a close shot of someone looking at something, then you cut to an apple— you combine the shots and create hunger,” Friquet said. “But in VR, you can actually make something go eat or absorb food.”

Of course, VR is not without its limitations, and the number one is the fact that you have unlimited virtual space, but limited physical space. Friquet said that there is no space for people to fully enjoy VR in an urban setting, because users would eventually hit a physical boundary in real life as they explore the unbounded virtual space, which would severely impact the experience. For him, VR headsets are still big, heavy with a cheap plastic smell, which constrains the body. The other problem is the lack of imagination and richness of the content.

“For the creators, we try to use the same formulas [like] zombie shooters, we try to have scary stuff, and that’s just sad because [VR] is a mesh of poetry to me,” Friquet said. “I want to go back to the limitation of too much expectation, too much desire to become mass adopted. We either have to be [as popular as] cell phones or like TVs [But I think] it’s okay to be small, we don’t have to create something better.”

Shah, who is working in the technological side of VR, said that the path for this industry is beyond debate, at least in terms of devices and technology.

“It’s led by Facebook, and then probably the next five years, Apple,” Shah said. “The trend is quite deterministic, it is going to be cheaper and more comfortable, better ergonomics for VR headsets, it’s going to switch to some form of mixed reality like HoloLens, and eventually is going to be a glasses format, where you put on a pair of glasses, and it will allow you to switch between fully immersive and augmented reality and mixed reality and all of that.”

And this creates another problem for Friquet, the question of who is leading the industry and telling the stories.

“It’s again, very American-centric,” he said. “The dominance of American culture and symbols of the stories that suppose, if it’s not zombies, it’s about superheroes and all that. In China, [there is a] famous epic book called Journey to the West, and the Monkey King is also in India. People need to experience the wealth of different stories. People see VR as an industry and a new business, but VR is art.”

Rashin said that with cheaper 360° cameras and quick, simple tutorials, more and more people will be able to access and use this technology. Shah, on the other hand, touched on the delicate balance that his company has to keep between making profits and conveying messages to people

“In the beginning, I wanted to do this, because I wanted to increase empathy for the ocean, one of my other co-founders wanted to do this because he thought it was really cool [and] it would excite people,” Shah said. “We thought this could be used for training of astronauts, because they have to simulate zero gravity and for training technical divers, and that turned out we were completely wrong.”

After their new invention got published on MIT Technology Review, their first contact was actually from a water slide manufacturer. “He said, ‘hey, we read about you guys making this underwater VR headset, but we want to put VR on a waterslide,’” Shah described. They now partner with water parks for VR slides and snorkeling, and this is their way to fund the company so that they can work on other products. This also allows them to find a way to advocate for ocean empathy since they are in charge of creating the storylines of the underwater world, which in itself is another gain that they never thought of.

For Friquet, as much as he wants to continue experimenting with aquatic VR experience, the pandemic has directed his attention to VR social experiences.

“I want to talk about trust [by] doing a multiplayer VR social experience, talking about paranoia.” he said. “The film that motivates me is The Thing by John Carpenter (1982), as well as the popular game Among Us.”

“For me, VR fulfills the promise of being someone else and somewhere else. So you create something you cannot in real life, you can do things that you cannot do in real life,” Friquet said.