No Ghost Land: Chinese Horror Growing Under Strict Censorship

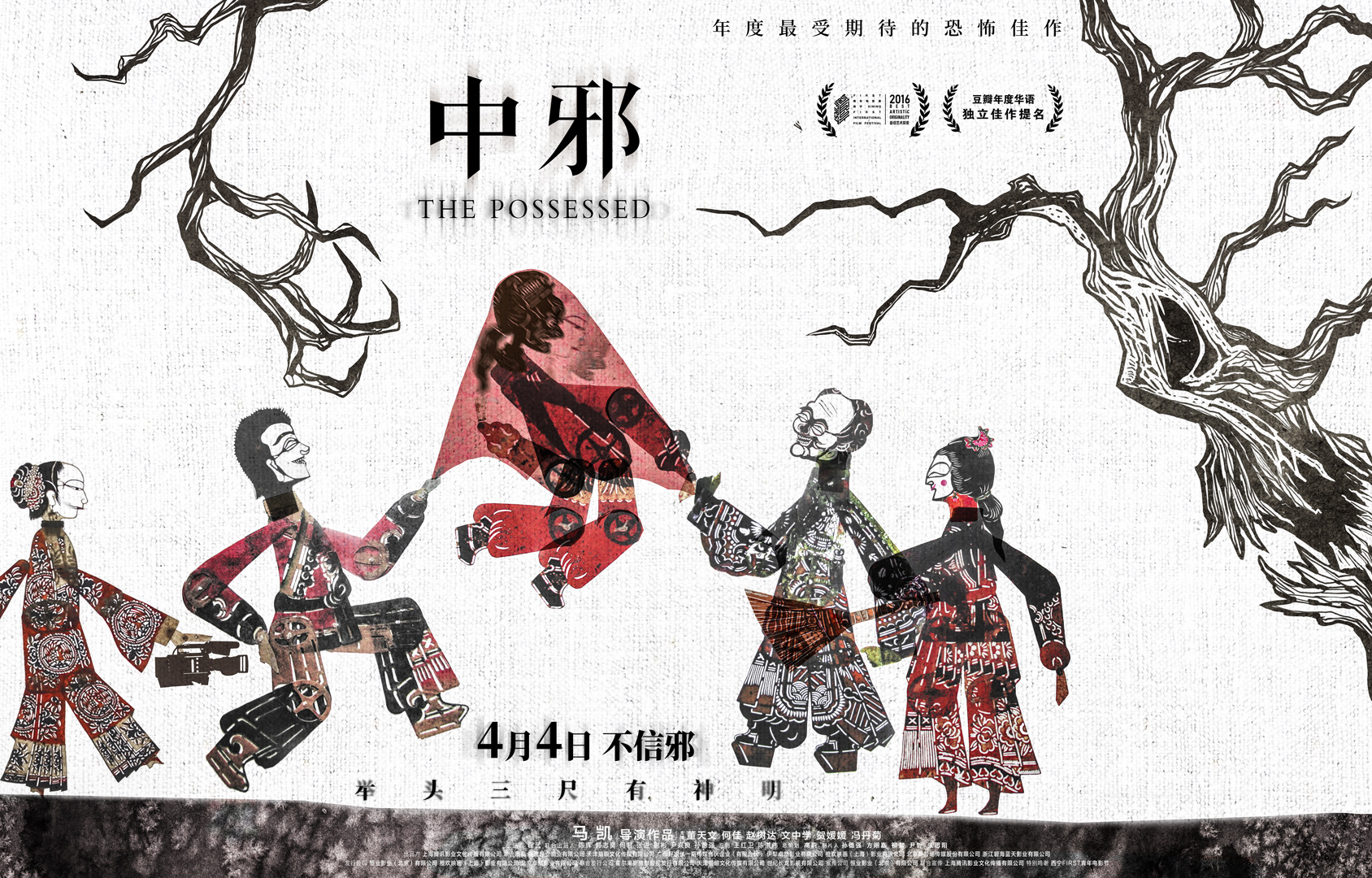

It feels like just yesterday when Kai Ma heard his name during the award ceremony of the 10th FIRST International Film Festival four years ago. The first word that caught his attention was “mockumentary,” and then the audience called out the name of his movie.

“The Possessed! The Possessed! The Possessed!”

Like waves flapping the reef and stirring layers of spoondrift, the chantings pounded his ears and carried his thoughts away from the ceremony. All of this felt like a dream. The movie – his first made with little to no budget – had gotten to the final round of a major film festival.

He was so excited that he had barely gotten any sleep. Ma had never received professional training in movie directing nor had gotten into any movie festivals. The closest experiences Ma had with filmmaking before “The Possessed” were walk-ons for other film and TV productions. The filming was not easy: They almost didn’t finish it because the lead actor fell off a dell and broke his spine. However, after spending only 10 days writing the script and 18 days filming with a small crew of 11 people, “The Possessed” went on to win the Best Artistic Originality award.

The next thing Ma knew after hearing his name, he was walking, almost running, toward the stage. He didn’t even see the stairs. He jumped to the stage.

After that night, Ma’s life was completely overturned. Many film investors came to him, expressing willingness to sponsor the reshooting and public screening of “The Possessed.” Awards and fame came as well. Not only did he receive another award during the 2017 Weibo Movie Awards Ceremony, but he also screened “The Possessed” in the Festival de Cannes in 2017.

The movie was remade and later scheduled to premiere at the Tomb-Sweeping Festival the following year. Ma received the exciting news in the middle of a dinner party, and he celebrated “with beer and a feast surrounded by friends.” Chinese horror lovers also rose with excitement when they heard the scheduling.

“We have waited 20 years for this moment,” wrote film critic Du Sir in his blog. “This movie is a revolution for Chinese horror.”

Everything seemed to be proceeding smoothly. Yet, what greeted both Ma and the eager horror fans was not a feast on the screen but something dishearteningly familiar: the movie was removed from the screening schedule.

On March 31, 2018, five days before its scheduled release in China, the movie’s official Weibo account posted the following announcement: “After consultation with all parties, due to technical reasons, ‘The Possessed’ has decided to rearrange the screening schedule and will announce it later in the future. We hereby apologize to all the movie theaters, media, and our fans.”

Like his audience, Ma was devastated when he learned of the cancellation news from a brief text message. To date, he is still not ready to unpack the incident. His project has received high rankings by users of the Chinese review-aggregation website Douban, averaging 6.8 points out of 10, and overwhelming positive feedback from professional filmmakers. Yet “The Possessed” was cut in cold blood, leaving only the “technical reasons” up for interpretation.

“Technical reasons” is a term often used in China as a euphemism for government censorship. Ever since the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, censorship in the entertainment industry has long accompanied directors and producers. Despite the obvious political motivations, one of the main intentions for horror censorship is to prevent and prohibit superstitious beliefs from gaining hold among the country’s citizens.

China has a long history deeply rooted in different religious and spiritual beliefs, mainly Buddhism and Taoism. In underdeveloped areas, which make up 40 percent of the total population, spiritual beliefs and rituals are indispensable. Because of this, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) believes if rural people are exposed to horror movies that include supernatural figures, they will take them seriously. And so, according to Article 25 of the Film Administration Regulation (2002), films are not allowed to show contents that are “propagating cults and superstition.”

Another reason why CCP is so eager to prohibit superstitious belief is that superstition goes against the party’s ideology in historical materialism, an essential part of Marxism. Materialism argues that the material world has an objective reality independent of mind and spirit. In other words, the party believes that ideas and beliefs, such as spirituality and religions, are products and reflections of material conditions. In order to solidify and further advocate for such beliefs, the government labels everything related to ghosts or spirits as unrealistic and imaginary superstitions that should be worked against.

And because of all the violence, supernatural elements, and anti-materialism ideologies, CCP has maintained a strict grip over the cinematic contents of the horror genre. As a result, Chinese horror has been under wraps, hidden from the movie industry for decades.

However, despite all the obstacles and resistances, the genre remains relatively alive in the Chinese movie industry thanks to the creators who have been putting in their effort to keep this genre going. Over the decades, directors like Ma have been trying to break the ceiling for Chinese horror, and such attempts are still in motion.

After all, the richness in ghost culture has provided Chinese creators with millions of inspirations, allowing filmmakers to play around and even coexist with the censorship.

The roots of horror can be traced all the way back to the Jin dynasties. According to historians, the first piece of horror literature was “In Search of the Supernatural,” written by Bao Gan (315-336). The book is about gods, ghosts, and other supernatural phenomena in China. Another famous literary work, and probably the most classic one, is “Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio” written by Songling Pu (1640-1715). This collection of short stories is about supernatural beings, and they have served as the inspiration for many Chinese horror movies and TV shows.

Two hundred years later, the first censor regulation was released during the Qing dynastie. At that time, China was forced to give up its policies of seclusion after WWI, resulting in countless novel foreign products flooding into the market, including film and theater production. The enrichment of the entertainment industry brought a wave of censorship from the government. In February 1926, after the first censor regulation, the Drama Unit of the Ministry of Education in Beijing established a film review group, which drafted another censorship policy, stipulating that domestic and foreign films “must be reviewed and approved by the Society before being allowed to be shown.”

Horror movies in China have never escaped the influence of censorship. The first Chinese horror movie “Song at Midnight” debuted in 1937 and struggled to deal with censorship and pressure from the National Government of the Republic of China. Besides its horror plot, the movie also included significant leftist political symbolism, which brought attention from the government. Eventually, the director was forced to revise and recut his film in order for it to be released.

The horror movie industry notably ceased after “Songs at Midnight” due to World War II and China’s post-war reconstruction. After the communist takeover of mainland China in 1949, the entertainment industry has served as a powerful tool for political propaganda and ideological edification. Yet, attributing all the censored movies to political reasons would be impossible since films have also been employed as a method for mass education and social inclusion. At that time, the government supported the film industry, which allowed officials to monitor the production and distribution of movies.

Because the CCP was still a newly established government entity, it pulled every string to get the Marxist ideology across to the public, educating its people into modern and rational citizens. Eventually such education came to an extreme. As a result, the Cultural Revolution took place in 1966. As a socio-political movement led by the government, the goal was to preserve communist ideology by purging the remnants of capitalism, including entertainment and traditional elements such as spiritual and religious beliefs, from Chinese society. Known as “a decade that has gone backward,” the movement was a devastating period for Chinese artists. Filmmakers, writers, and other artists were persecuted for having “old thoughts” and spreading “old culture.” The majority of artistic creators were condemned as bourgeois and anti-revolutionary. They were stripped of their creative status and were publicly humiliated and ravaged. Some were even imprisoned or sent to be “reformed” through hard labor. Many great artists committed suicide.

It wasn’t until the Chinese economic reform in the 80s that the movie industry was brought back to life. The reform was intended to establish a socialist market economy in China by opening up the country to foreign investment and private businesses. The success of the reform resulted in immense changes to Chinese society, forming the golden era in the entertainment industry during the 80s and 90s. Brilliant filmmakers were introduced outside of the mainland, mainly from Hong Kong, with their ideas and production skills.

The blooming entertainment industry allowed the opportunity for classic horror movies to emerge in the market. In 1988, the first serial killer character in Chinese film history made his debut. “The Silver Snake Case,” directed by Shaohong Li, was shamed for its extreme violent scenes by the State Administration of Radio, Film, and Television (SARFT). Yet the film somehow remained untouched. Audiences flocked to it, and the film became one of the most popular movies at that time.

Another milestone for the Chinese horror genre was “The Lonely Spirit in an Old Building,” directed by Ming Liang and Deyuan Mu. The film is the first to be labeled “Not for Children” by the government, which marked the emergence of China’s rating system. Tickets sold out quickly and the movie stole the thunder from “The Silver Snake Case,” creating five times more box office revenue than its cost.

Horror movies continued to thrive in the early 2000s. With the established foundation created in the 80s and 90s, Chinese horror movies, especially the Hong Kong cinema, were proliferating. Horror movies like “Mr. Vampire,” “Double Vision,” “Old Corpse in Mountain Village” and “Three” are all from that golden era and essential, unforgettable childhood memories for the upcoming generation of filmmakers.

Kai Ma is from that generation, and his passion for horror movies is part of what drove him to create his own. Growing up, he was obsessed with horror movies. Although most of the time he would have nightmares after nightmares, sometimes waking up in a cold sweat screaming with tears, Ma enjoyed the thrill.

Like Ma, Zhaoyuan Li, an aspiring movie director, is also a die-hard horror fan. Li started watching horror movies at a young age. He still remembers the night he watched “Old Corpse in Mountain Village” for the first time. Li couldn’t recall much about the plot, but the horrifying ghost, Chu Renmei, left an indelible imprint on his mind. Even now, the image of Chu Renmei still gives him goosebumps.

The reformation ended as the new generation of leadership took power. The new chairman of China, Jinping Xi, has rolled back many of the policies that affected different aspects of the country, including the movie industry. As part of the policy changes, the government combined the powers overseeing press and publication with those overseeing film and television, forming the State Administration of Press and Publication, Radio, Film, and Television (SAPPRFT). This further centered and strengthened the government control over the entertainment industry.

As a result, filmmakers and investors started to use horror as money makers rather than an artistic expression, profiting off of low budget movies of poor quality, especially after several big box office hits produced during the early 2010s. In 2011, “Mysterious Island” was released, earning 89 million yuan ($13,777,200) at the box office with a production cost of less than 5 million yuan ($774,000). In years that followed, 40 to 50 horror films were made and released almost every year, looking for ways to become the next “Mysterious Island.”

Such a return on investment drove capital into the horror market. In 2014, a landmark horror movie brought justice to the genre. Famous for its relatively delicate plot and special effects, “The House That Never Dies” gained a box office profit of 400 million yuan ($64,516,129), breaking 10 records in total, including the highest box office revenue, and becoming the peak of the Chinese horror film genre. In an enormous domino effect, numerous horror films followed one another after the release of “The House That Never Dies,” but most of them released quietly, and almost none of them received an overall positive review from the audience.

Meanwhile, the government was still trying to gain more control over the entertainment industry by further reforming film regulations and imposing even stricter censorship policies. In March, 2018, the Publicity Department transformed the SAPPRFT to form The National Radio and Television Administration (NRTA), transferring the oversight of the film industry, putting more government interference over film making.

What makes it worse is that the censors are not in the habit of explaining their decisions. Filmmakers often have to guess what is acceptable content, themes, and style. No one knows what’s going on behind the scenes. The last-minute cancellation that “The Possessed” suffered was not at all surprising. Last year, “One Second,” directed by Yimou Zhang, was also pulled from the Berlin Film Festival due to “technical reasons.” A few months later, the opening film of the 2019 Shanghai International Film Festival, “The Eight Hundred,” got removed only a day before its screening. And the reason was, again, “technical.”

The film reviewing process is also changing. To get a movie in theaters, filmmakers are required to first submit an outline for project approval from the administration. If they are filming a horror movie, filmmakers need to have the full script ready. After the shooting and editing is finished, filmmakers need to submit the complete project for another round of examination. But usually, and especially with horror, the movie would be returned with editing suggestions.

The process can be long and unpredictable, and sometimes films need to be reviewed not just by the publicity department. When Renhao Qian was making “The House That Never Dies II,” the movie didn’t get finalized until two weeks before its scheduled screening date. “You will need to send the movie to other offices, such as the National Medical Products Administration or the Public Security Bureau, if anything related is mentioned in it,” Qian says. Sometimes, experts such as historians would also join the reviewing and provide suggestions. “I have had this experience where the officer from the publicity department was trying to give filmmakers more freedom in creativity but was refused by other parties in the reviewing process.”

Oftentimes, horror filmmakers have to come up with a relatively scientific explanation at the end of the movie, clarifying that all the ghosts or monsters in previous plots are from the protagonists’ illusions. For example, in “The House That Never Dies,” the ghost is the result of drug abuse, while in its sequel, the ghost is due to methane inhalation. Directors and producers find ways to polish their stories in order to pass the censorship, no matter how absurd the plot might be.

The harsh censorship has put filmmakers between a rock and a hard place. For some creators, having no restrictions at all would be the most ideal. Zhe Yang, a screenwriter and director of “Medical Examiner Dr. Qin” and “Danger of Her,” believes that the Chinese film industry would thrive if censorship is abandoned.

He says that writing under so many restrictions has put him into self-denial. “Although my coworkers would always encourage me to explore further, it is so easy to fall into self-censoring when some of my work didn’t get approved for two years by the authorities.”

However, Qian thinks that strict censorship can force filmmakers to be creative and find different ways to avoid being censored. He believes that, “As a creator, you cannot blame everything on censorship. When you do that, you are censoring yourself.” Officials from the publicity department told him that if a movie is good enough, they would allow it. “The essential problem is about the script, not regulations,” Qian says. “The release of ‘The Bad Kids’ and ‘The Long Night’ is the best example. There are bad cops in the show, yet they still got approved. Why? Because they are telling good stories.”

In his opinion, opening up the market might not benefit the horror industry because “everyone would want to do it, and the quality of horror movies would be even worse.” The success of independent horror films like “The Possessed” is because horror is a huge genre with only a few good movies that make it through the filter of government intervention.

To Qian, the Chinese film industry is in its best times. “I still want to challenge myself, to make something new. I hope Chinese creators, especially young directors, can step out of the censored mindset and not be discouraged,” he says.

Two years have passed since the cancellation of “The Possessed” and though he’s still confused about the whole incident, Ma has moved on. He is now focusing on his new work, and has already finished another film, a horror-comedy.

Meanwhile, Li is planning to engage in advanced studies in directing. His passion is in horror, and his goal is to make a different kind of horror movie for Chinese audiences. Both of them are determined to do something different for the Chinese movie industry, to be the first ones that break the ceiling.

Regions: China