“The Six”: an Untold Story of Titanic’s Chinese Survivors

As a romance classic, “Titanic” broke many cinematic records and won 11 Oscars, setting unrealistic relationship expectations for a generation across the globe. The film’s touching finale is probably one of the most famous scenes, as Jack Dawson (Leonardo DiCaprio) slowly sinks into the ice-cold water while Rose DeWitt Bukater (Kate Winslet) desperately waits for a lifeboat.

However, little does the audience know that the last person rescued from the shipwreck inspired Director James Cameron’s creation of this classic scene. The passenger’s name was Wing Sun Fong, and he was one of the six Chinese survivors of the Titanic.

Although most Titanic survivors have told their stories, no one knows anything about these six men. In fact, most news and records of their survival are either negative, absent, or bluntly racist. Headlines such as “Chinese Coolies Save Their Lives By Clever Hiding” and “Disguised as Women, They Secure Places in Lifeboats” dominated the media narrative at the time. Joseph Bruce Ismay, the owner of the Titanic and another survivor of the sinking, stated that there were four “Chinaman or Philippinos” hiding “under the thwarts” in his lifeboat.

It wasn’t until recently that someone decided to tell the true story of these people. In 2021, a documentary about the Chinese passengers on the Titanic was released. Directed by Arthur Jones and produced by Tong Luo, “The Six” aims to find out what exactly happened to the Chinese survivors of the Titanic.

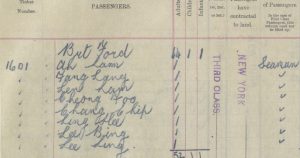

The documentary starts with a series of questions from Steven Schwankert, the lead researcher of the project. Like everyone else, he was surprised to know that there were Chinese people on board and that six out of eight had survived one of the most fatal incidents in the 20th century. Who were they? Where did they go after they got to New York? When more than 700 people made it out alive, and when almost every one of those stories is well-documented, why isn’t there any specific record regarding these six Chinese survivors?

Despite the fact that the Chinese passengers deserve to have their stories told like the rest of the survivors, their stories are not easy to find. Records about them are limited. And even if the researchers had a list of names, all of those were written in English, meaning that each pronunciation could represent dozens of Chinese characters that led to endless possibilities. Because of this, the research team could not identify one of the Chinese passengers, Foo Cheong.

In addition, according to Researcher Cynthia Lee, these Chinese men were sent directly to another ship, the Annetta, and departed for Cuba as sailors right after the tragedy. This added another layer of difficulty to the investigation. Their departure seems cruel yet inevitable as they were the least favored passengers—western countries did not greet Chinese people with welcoming gestures at that time.

Therefore, according to the documentary, “surviving the Titanic wasn’t the greatest obstacle they had to overcome in their lives.” Through the journey of finding these Chinese passengers, the movie presents an overview of the global immigration history of Chinese and western countries (specifically the United Kingdom, the United States, and Canada) as each survivor faced different circumstances in these places.

During WWI, many Chinese laborers came to Britain to fill in the blanks left by the local workers, most of whom went on to battlefields. However, unsurprisingly, the British government repatriated a lot of the Chinese seamen back to Asia after WWI due to labor redundancy and economic downfall. British people at that time were hostile towards foreigners and immigrants according to Researcher Clotilde Yap, who found the government’s hateful discourses regarding Chinese seamen’s repatriation in Britain’s national archives. As a result, a generation of the Chinese workforce was sent back to Asia. Among them, there might have been the two survivors Ah Lam and Hee Ling, who both disappeared after boarding a British ship to Asia.

A similar situation had developed in the U.S. and Canada. One of the survivors, Bing Lee, possibly ended up in Canada and opened a coffee shop. From the mid 19th century to around 1923, the Chinese immigrated to Canada, filling the labor need that Canada had. Lee could have been one of them, and he was lucky. After decades of benefiting from Chinese immigration, the Parliament of Canada passed the Chinese Immigration Act in 1923, banning most forms of Chinese immigration. According to the act, every Chinese person entering Canada had to pay 50 dollars, a sum later raised to 100 dollars, and finally to 500 dollars in the next couple of years. This was still more manageable than the U.S. Chinese Exclusion Act. At the very least, if one could pay the taxes, one would have the opportunity to move to Canada.

In the U.S., immigration discrimination against the Chinese had started much earlier. In 1882, President Chester A. Arthur signed the Chinese Exclusion Act, prohibiting any immigration of Chinese laborers. The legislation was the first, and remains the only, to have been implemented to prevent all members of a specific ethnic or national group from immigrating to the United States. As a result, many people tried to enter the country using fake identifications, and many of them ended up in Angel Island, a so-called immigration port that served as a detention camp for immigrants from different countries.

Those who changed their identity for immigration were usually called “paper son” and “paper daughter,” meaning that they illegally immigrated to the US by purchasing documentation stating that they were blood relatives of Chinese Americans who already had U.S. citizenship. In the film, evidence points out that Wing Sun Fong, the last person rescued from the ocean after the Titanic sank, could have been one of those paper sons, as the team contacted Wing Sun Fong’s family and found out that he had three different names in total: Lang Fang, which is the original one documented for Titanic, Sen Fang, and finally Wing Sun Fong.

In Fong’s family, no one really knew that he had survived the Titanic. His son, Tom Fong, heard the story from a family friend. Even then, he only knew that his father was involved in a shipwreck and was saved by a door plank, but he never made the connection between his father and the Titanic tragedy. Years later, Tom Fong’s cousin later briefly mentioned that Wing Sun Fong was on the Titanic, which led Tom Fong to investigate the incident. During his research, he found out his father had changed his name.

Many paper sons and paper daughters would keep the secret of their identity for life because the exposure of their true identity could cause a lot of trouble. They would destroy any paper evidence, like letters between family members, and try to be as secretive as possible. It has become a generational trauma for Chinese immigrants because they had to cut off all ties to their motherland to survive in this country and endure unimaginable pain from xenophobia and racism. Based on his compensation claims filed after the Titanic sank, Wing Sun Fong and his two other friends boarded a ship to the U.S. to become merchants, and potentially to start a business in Ohio. One of his friends even planned to get married. Yet, his friends died in the ocean in the end, and he had to start from square one.

Interestingly, the film pointed out that Cameron did film the scene where Wing Sun Fong was lying on the door and rescued by the lifeboat when making “Titanic.” With no knowledge of who that person was, Cameron took a wild guess—he asked another Chinese American on the production team to play this role. He got it right. Yet, unfortunately, the clip was eventually taken out of the movie, just like all the stories of these survivors in history. Instead, Rose became the one who lay on the plank and got rescued by the only returning lifeboat.

From the individual path of each Chinese survivor, the film depicts a story that goes beyond the Titanic shipwreck. “The Six” pieced together the struggles of each person into a map of Chinese immigration history. While watching the film, it is hard to ignore an ironic feeling. Despite the fact that the Titanic sank 100 years ago and that the immigration legislation targeting Chinese people has long been abolished, today’s society is not at all different from the one Wing Sun Fong experienced. According to the documentary, the Canadian Chinese Exclusion Act was not repealed until 24 years after its approval; and for the U.S., revocation of the law took 61 years.

Looking back, “The Six” feels like a long-overdue vindication for the Chinese survivors on the Titanic, a voice that shows people what actually happened that night. It demonstrates their survival not only during the shipwreck but also during a time of Western xenophobia and hostility. It tells people that those Chinese survivors were not cowards nor stowaways: They were only people who took a lifeline when they saw it, like everyone else who made it on the lifeboat, including Ismay himself.

Regions: China, United States