Titane: Murder, Cars and Daddy Issues

Director Julia Ducournau once again manages to create a grotesque whirlwind of a story with her new film “Titane.” After being featured in the Cannes International Film Festival and receiving the notorious Palm d’Or for 2021, it finally premiered in the U.S. on October 1st. Ducournau did not only shoot a well-crafted movie but used various storytelling devices to make this film horrifying yet enticing. Though you want to shield your eyes from the terrors in each scene, you cannot help but peek at the screen through the spaces between your fingers.

There are many moving parts to “Titane,” but the film revolves around Alexia (Agathe Rousselle), a serial killer with a titanium plate in her skull that causes her to lose connection to empathy. Before she embarks on a journey to escape the consequences of the murders, she becomes impregnated by a Cadillac.

“Titane” is a body-horror film through and through, but its commentary about sex and family is as central to the film as the gore. Alexia’s sexual behavior and her volatile experiences with family stem from her childhood trauma, as her father “caused” the crash that provoked her brain injury. The type of relationship that comes as a result of the crash resembles a theory coined by Freud: the Electra complex. Essentially, a child begins to develop sexual feelings for the opposite-sex parent while feelings of anger develop for the other parent. Though Alexia’s problematic relationship with father figures presents itself more clearly towards the end of the film, the car crash involving Alexia and her father jump-starts this type of relationship.

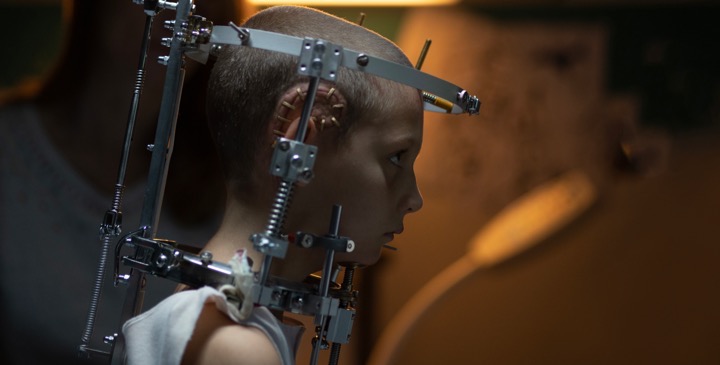

The crash scene in question is filled with tension and foreshadowing. The tension builds between young Alexia and her father as she kicks the back of his seat and hums annoyingly loud. In a second, the car spins and tumbles out of control, the first jump scare. It is followed by a few moments of silence as the frame stays stuck on the crash, with the beat-up car and blood dripping down the backseat window. Yet, even after sharing this harrowing experience, the tension remains. Released from the hospital with the titanium plate in her head, Alexia continues to resent her father.

However, the nature of the relationship changes as Alexia gets older, thus highlighting the theme of disconnected family. Towards the beginning of the film, her father examines her stomach after she complains about stomach pain. He could not detect any abnormalities, so he took his hands off her stomach. The commentary on family becomes clear when Alexia reaches out, grabs his hands, and forces them back on her stomach. They stare at each other for a few moments, enough where it feels awkward. He then yanks his hands back and leaves.

This strange and uncomfortable moment almost parallels the looks Alexia shares with her father after having the titanium put in her head. The moment they share illustrates that her father falls short of the father figure she needs. He can neither keep her safe nor offer comfort. This is another one of the moments where Ducournau comments on how Alexia’s trauma can further the disconnect between Alexia and her father.

This odd familial connection continues later on with Vincent (Vincent London). As Alexia impersonates Vincent’s missing son Adrien to escape the police, Vincent and Alexia develop a sort of familial relationship that develops sexual undertones after Vincent learns Alexia is not his son. Though Alexia does not have a healthy relationship with either father figure, her relationship with Vincent brings her more comfort. They learn to trust each other and work together as Alexia joins his firefighting group. They almost become surrogates for things they miss in their life. For Vincent, it is his son, and for Alexia it is empathy. Neither one of them is actually fulfilled because it is impossible for them to achieve what they actually want; Vincent’s son is not Alexia, and Alexia is a sociopath incapable of emotion.

In addition, we see the disconnection in her sexual experiences due to her trauma. Whether it’s her sexual relations with cars and trucks, murdering people in sexual settings, or her brief kiss with Vincent, her relationship with sex is not healthy. The car crash and the implantation of the titanium in her skull directly correlate with her sexual preference for cars.

We first learn about this in the scene with the dancers at the car show. Alexia is one of the hired dancers performing erotic dances on the displayed cars. Her seductive dancing on and with the vehicle suggests her sexual connection with the machinery. The hints become clearer while Alexia showers at the venue after the car show. Loud metallic banging noises and engine sounds interrupt her shower, so she investigates. She then realizes that the car, the same one she interacted with during the show, is attempting to get her attention. The scene cuts to Alexia and this Cadillac having intercourse. Her fascination with cars and machinery after her car crash links her trauma to her sexual encounters. Ultimately, Ducournau does a phenomenal job of showing Alexia’s messed-up connection between family, sex and her trauma.

Though I was immediately impressed with the themes in “Titane,” there were moments of confusion and frustration. Upon first screening, the combination of several themes, constant violence, chaotic plot and an unreliable narrator, made the film overwhelming, which was clearly Ducornau’s intention. The jarring violence and gore grow from when Alexia has sex with the car, to Alexia smashing her nose on a porcelain sink, or the way the skin on her stomach rips apart from her metallic womb growing. Known for her dedication to body-horror, Ducournau does not skimp on the gore, so the camera lingers on the grotesque actions playing on screen.

Our unreliable narrator, Alexia, deepens this confusion. In the beginning, I held no suspicions for how accurately Alexia portrayed reality. Nevertheless, as the movie progressed, I became suspicious of some elements. One instance is the scene when Alexia has sex with the Cadillac after the car show. The reason Alexia goes out to the car is due to the noises it takes to get her attention. The vehicle makes these noises on its own, not a person. This fictional and possibly hallucinatory element faces us with the fact that this is also psychological horror and sci-fi.

As Alexia interacts with the car and more seemingly impossible actions unfold, it feeds into the surreality of the movie. If you are someone like me and want to know exactly what is happening in a film, this film might frustrate you. The division between reality and what is in Alexia’s head never reaches a clear-cut point; especially with the final scenes,when Alexia gives birth to an infant that has titanium parts in its body like her.

However, this frustration remains a credit to the film. It is not the point of films like “Titane” to be realistic. All the gore, allusions to the Electra complex and mechanical undertones make this film more surreal than logical. The emphasis of this film is to visually horrify audiences and use those visuals to comment on how trauma, family and sex connect to each other. Ducournau’s film seeks to evoke pain, horror and sadness. Ultimately, Alexia’s lack of empathy makes her a victim and a murderer because of her trauma.

Regions: Boston