The New York Jewish Film Festival Jan. 12-25

Senior Film Critic Kurt Brokaw picks virtual favorites from a hybrid festival that won’t surrender to Omicron

Just when you thought it was safe to go back into the movies—maybe it’s not. Especially if, like this viewer, you’ve been isolated with days and nights of fever and chills this month—what’s turned out to be a “light” Covid breakthrough. While major national film festivals like Sundance and Palm Springs have gone virtual or canceled entirely, Manhattan’s JCC pivoted its third annual Cinematters fest to five days of virtual showings in January. Meanwhile, this NYJFF (sponsored by Film at Lincoln Center and The Jewish Museum) elected a hybrid path for its 31st year, showing some selections in person, while streaming others.

It’s a strategy that recognizes the ambivalence many New Yorkers feel about attending in person events, masked and with ID’d proof of vaccination, in the midst of a state infection rate hovering at 22% at this writing (January 8th). It also illustrates that NYJFF’s core constituencies may no longer be just vulnerable elders, retired public school teachers, and all those red-diaper babies who traditionally bus or subway down to the Walter Reade Theater on the Upper West Side.

What’s clear is that supporting in person indie cinema at the start of this new year presents a certain risk. This press corp remembers our elder statesman, William Wolf, perished on March 28, 2020. Bill was 94 and seemed in robust health when we walked out of MoMA’s last screening of the New Directors fest on March 12th, and barely two weeks later Bill was dead from Covid-19. We honor his life.

A desktop screen, 12″x19″, can’t compare with a Lincoln Center screen 19 feet high and 35 feet wide. An IMac will never equal IMAX in any theatrical setting, anywhere on earth. But it can still transmit the same surprising, even profound ideas, not just in feature films but in the shortest shorts. Here are five of the best features and shorts from this year’s NYJFF:

The Lost Film of Nuremberg: Jean-Christophe Klotz: France/Germany: 2021: 52 minutes

The shadow of World War II hangs heavy over the New York Jewish Film Festival. It almost always does. It’s not on a banner but it’s felt by many patrons: ‘Never Forget.’ This edition’s most significant film concerns the first trial of Nazi leaders accused of murder, held in Nuremberg, Germany in the fall of 1945. The unprecedented plan of the U.S. prosecution team, headed by a Supreme Court justice, was to show photos and especially films that would demonstrate beyond words the ‘crimes against humanity’ during the Holocaust. The prosecution’s primary strategy was to let the films themselves condemn the accused.

In 1948, a 78-minute documentary of the trial and much of the footage that helped convict the Nazi murderers was created. Titled Nuremberg, it was intended to be seen by the world. It wasn’t. Written and directed by Stuart Schulberg, brother of the better-known screenwriter and novelist, Budd Schulberg, the documentary was suppressed, for reasons you’ll shortly discover. In 2010 a restoration of Nuremberg by Sandra Schulberg (Stuart’s daughter) and Josh Waletzky, narrated by Liev Schreiber, briefly played in New York City at the Film Forum, and was praised in a review by lead critic A.O. Scott in The New York Times.

Two issues were left answered: Why did Schulberg’s film never get a general release? And how did Sandra, Stuart and Budd—the sons and granddaughter of Paramount’s studio chief B.P. Schulberg—get involved in this project to begin with? How did they ever find the four hours of footage (titled The Nazi Plan and Nazi Concentration Camps in their courtroom screenings) that helped convict the 21 high-ranking Nazi officials? These are the fascinating questions that Klotz’ new 52-minute documentary has at last answered.

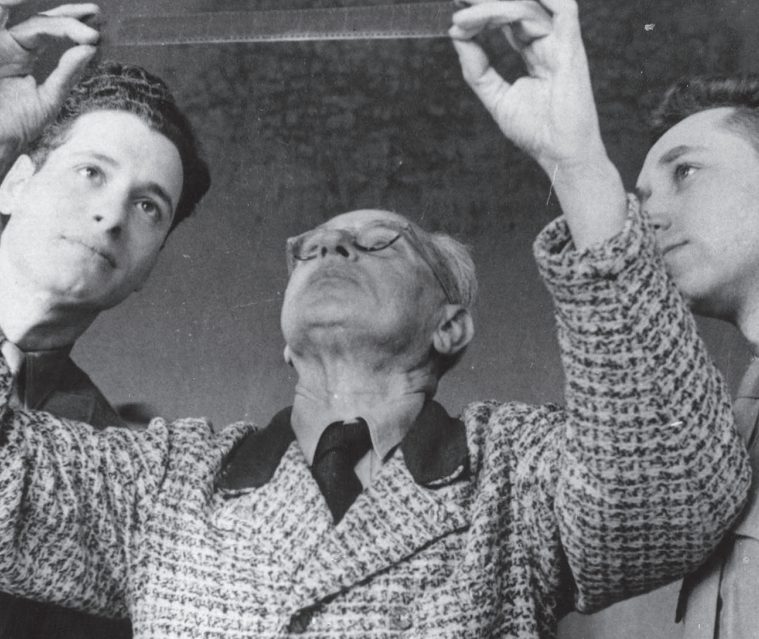

The Office of Special Services (OSS) tasked legendary Hollywood director John Ford, who headed its Field Photographic Unit, to put together a search team to try and locate film evidence of the Holocaust. Ford chose author Budd Schulberg, who’d just published What Makes Sammy Run? and his brother Stuart, (who’d later become a feature film producer), and ordered them to Europe. Budd was 30 and as a Navy lieutenant became the project supervisor; Stuart was 21, the youngest member of the film team.

Fox Movietone newsreels of book burnings and urban Jewish prosecution, along with viewings of Leni Riefenstal’s Triumph of the Will, helped them identify key Nazi leaders as well as various German cities to search—with only three months before the start of the trial. The courtroom had to be re-set so its theater-size screen could be properly viewed by the judges. Hitler’s personal photographer was arrested and his files were confiscated. The Schulberg team began to see that much of the footage they were seeking of Jewish suffering was initiated by the Nazi leaders on trial. The SS film teams considered them ‘vanity films’ for their bosses.

Schulberg discovered the frustrations of trying to track down the true horrors of the Holocaust. Scores of cans of film all through Germany were frantically destroyed as the Nazis sensed imminent defeat. When Schulberg hears of a stupendous cache of revealing films stashed somewhere in the Soviet sector, he gets an unexpected break: His contact, a Russian major, is a great fan of John Ford! Imagine, the man’s written two books on Ford. Schulberg recalls being told to “bring a truck—we’ve got all the film and negatives you need.” This haul proves to contain much of the defining evidence the OSS has been seeking. At the trial, the Nazi defendants, viewing what they’ve ordered yet consistently denied, are devastated. All but three are found guilty and hanged, commit suicide, or die in prison.

So what happened to Stuart Schulberg’s original 1947 edit? His daughter cites differences in governmental opinion whether the Schulberg film should have been made available just to German audiences, or to viewers throughout the world. With the unexpected Russian blockade of Germany, the Cold War officially began. Western Germany flipped and became our ally, Russia overnight became our enemy. Our Secretary of the Army, with the concurrence of German’s military higher-ups, canceled the release of Schulberg’s Nuremberg. It got a showing in Stuttgart and another in Manhattan, prompting the Times’s review. Even with Sandra Schulberg’s courageous decision to restore her father’s film, now retitled Nuremberg: Its Lessons for Today, and available in 13 languages, it hasn’t found a general release.

But Soltz’ Lost Film of Nuremberg could.

A Kaddish for Bernie Madoff: Alicia J. Rose :USA: 2021:75 minutes

This is the fest’s maverick movie, a bizarrely cinematic wild card. Director Rose warns you correctly when she describes her debut feature as “the most accessible experimental film people will see.” It grows out of a one-woman chamber-rock opera that premiered at Joe’s Pub, a popular downtown watering hole flanking New York’s Public Theater, almost a decade ago. You might describe its star, Alicia Jo Rabins, as a quicksilver mix of Sandra Bernhardt and Randy Rainbow. She has five albums in release plus another cabaret act, Girls in Trouble, about the frustrations of women studying Torah. She’s toured with a Klezmer/punk band. She bristles with Jewish feminist attitude. And she’s always front and center, acting and singing away in half a dozen roles, through 75 minutes that can sometimes feel tedious. “Enough already,” you may be tempted to mutter through your mask.

What’s more, Rabin’s very concept is suspect—who’d think of saying Kaddish for a Jewish American very much alive in 2009, who cheated thousands of trusting investors out of their life savings over two decades? Madoff didn’t die until last April, serving a 150-year sentence for securities fraud and money laundering, running the most outrageous Ponzi scheme in Wall Street history. Who’d show a musical of this monstrous treachery in America’s most closely watched Jewish film festival?

Like the two Alicias, and certainly like Sandra and Randy, NYJFF was thinking outside the box. Boldly. Fearlessly. Sometimes ferociously. And sometimes investing an hour or two pays off with a movie so knock-kneed and out of kilter with one’s own concepts of goodness and righteousness and order in the world, that in its own unorthodox way (no pun intended here), it works. This is the case with Bernie. Here’s one musical satire you figure has no right to win your admiration but somehow does.

Rabins’ story begins in 2008, when she was working on an empty floor—some failed business venture— in an office building on Wall Street that had been ceded by the landlord for a year to empty-pockets artists. A tax write-off or something. Alicia could ride her bike in from Brooklyn to practice her violin before and after her day hustle, which was teaching girls how to chant from the Torah.

Then the headlines: “Bernie Madoff arrested over $50 billion fraud.” Alicia thinks Bernie looks like her dad and starts a scrapbook that spills onto her walls. Bernie becomes Alicia’s obsession. Her fellow artists and even Alicia’s mom, who are up to speed on the growing mountain of Jewish lives Bernie’s ruined, think Alicia’s lost it. Cue the first song, with Alicia continuing her tale playing a bank manager sensing errant securities. Got it? She’s funny, and worse, she’s credible. Zak Margolis’ beautifully animated flowers drift down onto her banker’s desk, confirming we’re entering a peculiar mindset in some twilight zone.

Alicia ruminates on the Palm Beach Jewish enclaves that Bernie belonged to, now in financial ruins. Maybe these widows and retirees should perform a premature Kaddish, but that couldn’t occur in 2009 unless Bernie were to be excommunicated, a rare occurrence even in Palm Beach. Alicia begins to feel shame and guilt that an Eastern European Jew like herself could be so evil. She pours through the Madoff tell-all books on the bestseller lists. Cue the next songs, with Alicia playing a wacky economics prof, then an FBI agent. The lyrics are sharp and ring true, and about now you may start to lean in to this movie-within-a-movie that’s slowly pulling Alicia into understanding Bernie’s paths of wrongdoing.

It’s a basic structure you may recognize from early rock operas like Lou Reed’s Berlin and The Who’s Tommy. The issue here is how a genius becomes a pariah, confined to in house arrest with sons who longer speak to him and condo neighbors who turn their backs on him. Alicia tries out her work in progress in her rent-free office, before her other penniless artists. They all applaud it. As you’ll note, the Alicias are not shy about manipulating the feelings of “people like us” every which way, mixing together affinity schemes, equity formulas, psychoanalytic therapies, Biblical verses and suicides—all sheathed in bouncy arrangements and accomplished musicianship.

“Very few people knew he was just makin’ shit up,” sings Alicia, now suited up with a short hair wig, as a lawyer. Her character posits the idea there’s a little Bernie Madoff in all of us, telling people what they want to hear in a democracy that encourages investors to keep piling up the wealth, regardless of its risk. Alicia plays her violin on Wall Street, busking for change. She begins to sense that confronting Bernie means confronting herself. Maybe it’s easier to excommunicate the bum.

Rabins stubbornly holds the screen and your attention even when you’re uncertain how she’s going to resolve the morass she’s stirred to boiling. A Kaddish for Bernie Madoff is hardly the most uplifting picture to watch with a dangerous infection blowin’ in the wind, but say this: Anyway you look at it, it’s a breath of fresh cinematic air.

Mazel Tov: Eli Zuzovsky: Israel/USA: 2021: 25 minutes

Take a close look at Adam Weizmann, acted by a perfectly cast Peter Knoller and pictured here. He’s the bar mitzvah boy of every Jewish mother’s dreams—cute as a button, observant, quietly shy yet modestly forthcoming. His teacher proclaims him a Nobel or Pulitzer Prize winning lad in the making, and he’s preparing to sing a song in his handsome suit and tie, right after the slideshow and a few numbers by the adoring teen girls around him. Adam’s joyous coming-of-age party is taking place in 2008 in a banquet hall in Natanya, a sophisticated Israeli city of means. We’re ready to watch the happiest of events unfold, but writer/director Zuzovsky has something very different in mind.

Even as the DJ whips the sound and lights along, and guests dig into the catered feast with its delicacies like sheep testicles and passion fruit desserts, things are amiss. Adam’s dad isn’t there and has been missing for two days. His mom (the radiant Maya Dagan) is getting drunker and meaner by the minute, determined to end a 20-year marriage on her son’s bar mitzvah. Adam wanders outside the hall and spots a male relative in the shadows engaged in a sex act with another man. Adam himself is starting to longingly eye a blue sequin dress worn by a sweet classmate. And then the sirens sound—Natanya in 2008 suffered aerial bombardments during the Gaza war. All the guests dive under tables or pile downstairs into a basement bomb shelter.

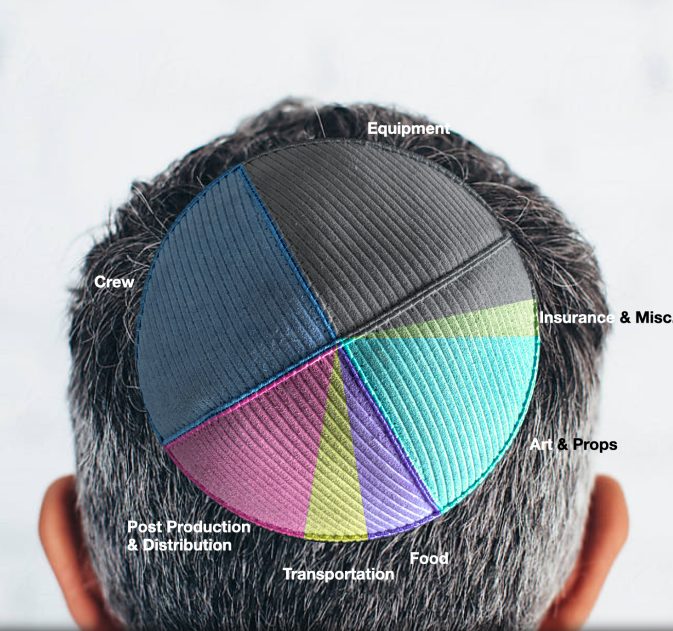

Mazel Tov was Zuzovsky’s thesis film at Harvard, and it may be the most accomplished slow motion train wreck of a bar mitzvah celebration you’ll ever witness. He’s assembled a splendid cast, first-rate credits including a super-supportive music score, and a 2008 point of view that’s based on a novella by Arnold van Gennep (“Rites of Passage”), braided with the director’s own experience. Mazel Tov was shortlisted for an Ophir award (Israel’s Oscar). Zuzovsky has been editor of Bamhane, Israel’s oldest weekly magazine, and in addition to his writing and filmmaking talents has quite an eye for promotion. Pictured is his unique diagram for end-of-filming financial requests, cleverly turning a pie chart into a yarmulke chart showing exactly where donations will go— from post-production, transportation and food to arts & props, insurance, equipment and crew. Watch this guy.

Beregovsky #136: Yoav Potash: USA: 2021: 4 minutes

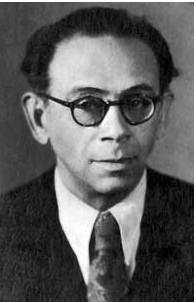

Ukraine is making plenty of headlines these days, encircled on all sides by mammoth Russian forces. Leave it to the NYJFF to spot and spotlight a cultural hero of Ukraine, Moisei Beregovsky (1892-1961), the country’s leading ethnomusicologist. A teacher and archivist, he taught everywhere from the Kiev Conservatory to ghettos and a Jewish children’s orphanage near Moscow.

Beregovsky had an abiding interest in Klezmer music, leading expeditions and making field recordings of Jewish and Ukrainian folk songs, including many Klezmer compositions. All told through the 1930s and 40s, he made and preserved over 2,000 compositions on 700 phonograph cylinders.

Yoav Potash had the bright idea of shooting Saul Goodman’s Klezmer Band (featuring clarinetist/narrator Mike Perlmutter and violinist Ilana Sherev) playing a short example (#136) near its California roots. Goodman’s band hires out for weddings, bar and bat mitzvah parties in the San Francisco Bay Area. Potash matched their keening instrumental to historical photographs of everyday Jewish life in the 1930s (from the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum). The result is serendipity—an authentic cinematic record of pleasant Jewish activities in Ukraine, Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia and Lithuania. It’s cut to the music, and in one joyous Fresylekhs (circle dance), the match to the music is sublime. As the band’s slogan says, “it’s a simcha with Saul.”

Lily: Adrienne Gruben: USA: 2019: 26 minutes

Comic books are a healthy industry in Manhattan. Nearly all comics shops around town have survived the pandemic, and the one in this writer’s neighborhood just moved across its avenue into larger space. Comic fans toss off their passion and deep knowledge like any true vinyl collector or cinephile. Lily Renée Phillips has been celebrated in the comic world for years as the Fiction House illustrator of Señorita Rio in issues of Fight in the mid-1940s.

Lily’s been the subject of innumerable write-ups, in addition to being honored at comic cons as the lone female drawer and inker in the first half of the 20th century. Trina Robbins’ biography, Lily Renée, Escape Artist (Graphic Universe, 2011) documents her upbringing in Europe and the wartime years illustrating (and writing) books, plays and comics in New York. Mitch Maglio’s Fiction House: From Pulps to Panels, From Jungles to Space (Yoe Books, 2017) celebrates Lily’s Good Girl art. She was given the Inkpot Award at the 2007 International Comic-Con. And here she is on film, at last, padding about her tony home near 72nd and Madison, humbly and matter-of-factly sharing more memories of a lifetime. Lily will be 101 (let’s repeat that, one hundred and one years of age) this May, and it’s high time she takes a victory lap at a New York Jewish Film Festival.

Adrienne Gruben’s affectionate doc devotes only a few minutes to Señorita Rio, but two of Lily’s issues, signed as “L. Renée,” are displayed below. Rio never seriously challenged Sheena, Queen of the Jungle, as a Fiction House cash cow, but she made her mark as a starlet-by-day, Nazi-fighter by night. In Gruben’s invaluable documentary, Lily describes how she escaped the Nazi annexation of Austria in 1938, traveling to England via Kindertransport and reuniting with her parents in New York two years later.

Lily’s own brush with the enemy is vividly recalled, when she was confronted by an SS officer, towering above her in Vienna. We see a black-and-white illustration of herself as a young, frightened teen, fearing she’d be locked in a synagogue which would be set on fire. Lily never lost her pulpy, chiaroscuro density in drawing bad guys. We get a first-hand, guided tour of much more of her preserved work, which alternates formal portraiture and pretty-shopgirls-on-a-budget strolling Fifth Avenue, with darkly rich costuming and a fantasy world of magic, ghosts, cats and bees that beckoned her from childhood.

She had no regrets moving away from comics in the 1950s. After all, Lily had been one of only two females employed at Fiction House on fashionable Fifth Avenue for years, “and all those male artists ever talked about was sex.” One gets the feeling she’s probably traipsed to her last personal appearance at a comic convention. What she’d really like to have in her apartment is more pictures of her grown daughter. Just what you’d expect to hear from a quintessential (and thoroughly delightful) Upper East Sider looking into her second century.

This concludes critic’s choices. Watch for Brokaw’s picks in Rendez-Vous with French Cinema, March 4-14.

Regions: New York City