Interview: Filmmaker Tom Gilroy Talks Independent

Every morning, New York-based interdisciplinary artist Tom Gilroy consults his cats, Ocean and Wanda, for ideas. His work spans across photography, theatre, acting, writing, poetry, and music, with independent feature films as his central focus.

Gilroy has written and directed three notable films: the critically-acclaimed feature “Spring Forward” starring Liev Schreiber, “The Cold Lands,” and the short “Touch Base,” the latter two both starring Lili Taylor. Growing up, I knew and referred to Tom Gilroy simply as “Uncle Tom” as he’s been a friend of my family for over twenty years. With Gilroy’s latest feature currently in development, however, I hadn’t seen or talked to him in quite some time.

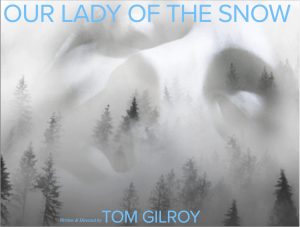

For the past six years, Gilroy has been working on “Our Lady of the Snow,” a spiritual thriller about nuns who experience ecstatic visions at a gothic convent. It stars Isabella Rosselini, Grace Zabriskie, and Jared Harris. Curious to learn more about his career and hear his unique perspective on the independent filmmaking industry, I reached out to Gilroy for an interview and a long-overdue catching-up session.

Caitlin Taylor So: How would an independent filmmaker like yourself define and categorize this genre, especially now in the age of streaming?

Tom Gilroy: Independent means something different now than when it first started. I first started in the late-’80s and back then, it really meant independent as in I would borrow 50 grand from someone, say your dad, and another 50 grand from your uncle, and then go out and make a movie with friends for $100,000. You didn’t have to answer to anybody. There was a national network of independent theaters, which you could then call up and say, “I have this movie, I made it. Can you show it?” By going around the country and submitting the film to festivals, you would hopefully receive enough praise and awards to generate ticket sales to pay everyone back and maybe even make a profit.

These kinds of films eventually started to become so popular that Hollywood took notice. Hollywood executives were hiring indie directors to make movies that were in the spirit of independent films, yet funded by major studios. When you’re making a movie for a corporation such as Amazon, they dictate to the director what they want or don’t want in the film. If you don’t agree, they don’t finance the film. If you come to them with an independently financed film for distribution online, they can also ask you to change and take things out. If you don’t, you’ll have to reach out to another platform. In both cases, the corporation is deciding what the audience sees, not the director.

The definition of independent started with the director being in charge with very low means, and got co-opted a little bit by the industry to the point where we are now. An independent film is no longer defined by the extent to which the director is making all the creative decisions; it’s by the director compromising with a corporation on what the audience gets to see.

CTS: Do you like the direction the independent filmmaking industry is heading toward and how it has evolved since you started your career?

TG: To my dismay, in spite of streaming, people, especially people your age, are seeing a less and less truly independent vision in culture in general. When I was your age, I was drawn to independent films because it was an art form where no one was telling people what to do. So for an audience, we were witnessing this completely raw and creative energy. It’s purely the vision of the people making it. That no longer exists for most of the culture that you consume today.

So, to answer your question, no. More and more of what you see now is completely homogenized because of the corrupting influence of money.

CTS: You once stated in a 2014 interview with San Francisco Film Society that you saw money as the greatest challenge for filmmakers. Would you say this is still the case today and if so, have you found new ways or opportunities to adapt to and resist the instinctive commercialization of cinema?

TG: I think I have. I just came back from Sundance, the Institute, which is totally about people being able to have a completely independent vision and voice. Through the Catalyst program, independent filmmakers can receive funding for their films. My latest feature, “Our Lady of the Snow” is budgeted at $3 million. And there are new opportunities for filmmakers that don’t require so much money. I think someone like you and your friends can make a $30,000 film on your iPhones and cut it with a program like iMovie. There’s a great feature about two transgender sex workers called “Tangerine” that a friend of mine, Sean Baker, shot using iPhones. That’s an example of how the challenge of money can be taken out of the equation. There are real expenses that simply having a phone doesn’t solve, such as feeding your crew, but believe me, your generation is better off and has more access than ever.

CTS: What are your thoughts on independent filmmakers looking to non-fungible tokens (NFTs) for monetization?

TG: People monetized their films already with tokens. Except they weren’t called tokens. They were books or prints or storyboards or DVDs or soundtracks. When I was raising money for “The Cold Lands,” we had a Kickstarter program. And if you pledged a certain amount, you received one of my storyboards. That’s a fungible token. I don’t have a lot of respect for the whole idea of non-fungible tokens or cryptocurrency though. My idol, musician and artist Brian Eno, put it perfectly when he described NFTs as “a way for artists to get a little piece of the action from global capitalism, our own cute little version of financialization.” The craze behind NFTs is greed.

CTS: Were there any standout independent films that inspired and informed your career?

TG: Oh God, I mean, there are hundreds, thousands. There’s a film called “The Hours and Times” by this guy, Christopher Münch, who became a very good friend of mine. He was part of the Queer New Wave of cinema. It’s about John Lennon and the manager of the Beatles, Brian Epstein, showing the fictional history of a weekend trip between the two. It was always rumored that Epstein, who was gay, had a crush on Lennon and that Lennon kind of took advantage of that to get Epstein to be super dedicated to the Beatles. It’s an incredible movie and was made for like $30,000. That movie was incredibly influential to me.

CTS: You’ve been working on your feature “Our Lady of the Snow” for six years now. Can you tell me where in the process you are for this project and how the pandemic disrupted or complicated your plans?

TG: Six years is not that long for an independent film. It is so far the longest that I’ve taken for any of my projects, but that just means I was lucky on the earlier ones. I started writing “Our Lady of the Snow” a little over six years ago and I just got back from Sundance Catalyst. Because we had the imprimatur of being a Sundance Catalyst film, we were able to raise close to about a third of the budget. Not too long ago, two other investors called and may come in for another $300,000 or something each. That would bring us to about $1.6 million.

The feature has to be shot in the winter and obviously, the pandemic blew that for the last two years. There was a slight chance we could film it this past winter, but Omicron came. The film takes place in a convent with a bunch of women in their 70s. So very high-risk people, even if they’re vaccinated. The protocols to protect actors and the crew were also costly. The window of opportunity for snow this year was getting smaller and smaller, so I thought, let’s wait another year. This gives us more time to raise money and further refine our vision. And hopefully, the pandemic itself will be further in the rearview mirror that actors will feel more comfortable.

Another deterrent alongside melting snow was the realization that maybe the species was being wiped out, so making a film…not exactly on the top of my priority list.

CTS: In 2020, during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, you wrote and produced a short titled “#WaynesvilleStrong” with “Orange is the New Black” actor Nick Sandow. Can you tell me a little bit about what it was like working around COVID-19 restrictions and solely relying on an iPhone 10 to shoot?

TG: Nick Sandow is a member of my theatre company so we have done many, many projects together. With such a long creative history, it made it easier for us to exchange ideas on what this piece should be without ever being in the same room. We had complete faith in each other.

I wanted to make a film about a guy trapped in his basement during a pandemic. We realized it had to be done in one continuous shot to heighten this sense of growing paranoia. I wrote a couple of drafts and would send them over to Nick. He would read it and then come back to me with questions and clarifications. I talked to my cinematographer who lives over in Park Slope to figure out what iPhone and lens I should use. Nick rehearsed for me over FaceTime and PhotoBooth and I would direct him. That took about a week and a half. We had a separate microphone so that we weren’t solely relying on the iPhone audio. For about five days in a row, Nick did take after take with me giving him notes.

In the end, we chose the best version. I called a friend of mine who’s an editor who created all the graphics. So it was created by just the three of us. We started submitting it to festivals. Some of them rejected it because it’s a long short, but Nick won an award for his performance from the IMDB Shorts Festival. After that, we sent it out to our friends who then posted it on their socials. It was an independent form of not just production, but distribution as well. For us as artists, it was great that we were able to create something in quarantine that addressed the pandemic and expressed our political views.

CTS: Can you walk me through a typical day in your life and how you use and manage your time to work on ongoing projects? How often does random creative inspiration strike?

TG: I go through periods where I’m writing every day when someone has either hired me for a job or when there’s a thing I’ve been thinking about and that thing is ready to come out. When I realize that’s happening, I get up every day at about a quarter to six. I come downstairs and have like three coffees, I converse with the cats, sometimes asking them for ideas, and by 6:30 a.m., I am sitting in front of my computer, in my office, no emails, no news, no nothing, only music without lyrics, and I start writing. I do that for a minimum of three hours before I leave the room, unless it’s to go to the bathroom. That usually starts to wrap up at around 11:30. That’s what I call “pure creative time,” where you’re literally pulling ideas out of the air and not judging them.

Every writer, especially someone your age, has to develop some form of daily discipline in order to grow and to understand what they actually think. Writers are inventing thought, not transcribing it. If you want to be an artist, you need to develop your own voice. Discipline is the foundation, but I also derive random inspiration from doing the most mundane things. I love folding laundry and washing dishes, for example.

CTS: What advice would you give to aspiring independent filmmakers today?

TG: Keep making shit. Don’t think that everything you make has to be the complete summation of your entire life and every creative choice you’ve ever made. It has to be the best you can make it at that moment. And then five months later, you might be looking at it and going “This sucks, I can’t believe it,” but you still keep making stuff over and over and over. That’s what you’re here to do. You don’t wait. Make shit every day. Discipline is so important.

CTS: What do you predict and hope for the future of independent filmmaking?

TG: I would hope that more projects are made that are in direct opposition to mainstream ideas that often are financed by large corporations. So anybody that thinks outside of that, even if I don’t love the piece itself, I applaud that person.

I hope that cell phones and the pandemic and this so-called Great Resignation will inspire people to just go “You know what, I want to make a bunch of slow-motion cat videos, write my own poetry over it, have my girlfriend play the tambourine in the background, and show them in my friend’s restaurant.” To me, that would be great instead of “I want to create a web series that’ll become the next Girls or Sex in the City,” because now you’ve copied this thing. I want people to be more experimental. Who benefits from people making independent films that are exactly like Marvel movies but cost less? It’ll be the same tired story over and over again.