The Demise of Mid-Budget Cinema

Trying to get a movie financed in 2022? Good luck unless you can produce the next blockbuster fantasy flick or adventure saga. Bonus points if the protagonist comes from a famous franchise or you can remake a classic, then the chances of getting money increase.

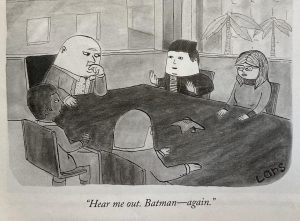

In our current film landscape, superhero blockbusters get pumped out like clockwork while films with medium-sized budgets serve as a relic of the pre-internet age. This “go-big-or-go-home,” “swing-for-the-fences” proposition involves pouring hundreds of millions of dollars into advanced cinematography and long-term promotional campaigns.

As the movie-going experience adapts to our viewing pleasures, studios have taken note, opting to produce higher-cost, higher-revenue films over less costly, less revenue-generating productions. Due to competition with today’s countless entertainment options — streaming services and social media platforms in particular — studios know a film must have a buzz to bring the bodies to the theater, which comic book movies typically do.

The proof is in the numbers. Following the release of “Iron Man” in 2008, the Marvel Cinematic Universe saw $585 million from a $140 million budget. While “Thor,” “Captain America,” “Guardians of the Galaxy,” and “Spiderman” all had similar financial success, 2019’s “Avengers: Endgame” made $2.7 billion on a $356 million budget, the second-highest (inflation-adjusted) grossing film of all time. Money talks, and the MCU’s success told Hollywood that superheroes sell.

Although DC Comics achieved box office prosperity and critical acclaim for their “Batman” and “Superman” franchises in the 80s and 90s, 2008’s “The Dark Knight” reached a new stratosphere of success, generating over a billion dollars on a $285 million budget and receiving eight academy award nominations. Other films such as 2016’s “Suicide Squad” ($175 million budget, $745 million gross), 2017’s “Wonder Woman” ($149 million budget, $822 million gross), and 2018’s “Aquaman” ($160 million budget, $1.1 billion gross) proved that superheroes lead to super profits.

However, 2022 strayed from the norm, focusing on air force pilots over comic book legends. Since its release, “Top Gun: Maverick” has made $1.4 billion (and counting) on a $170 million budget. With an established brand from the original 1986 film, Paramount Pictures flanked original Maverick Tom Cruise with a star from his generation (Val Kilmer), a TV star who’s made the foray into movies (Jon Hamm), a prolific actor who’s not as famous as his talent would suggest (Miles Teller), and a longtime Hollywood stalwart (Ed Harris). A smashing success, “Top Gun” won the approval of everyone from the high-minded film snobs to the thrill-seeking casuals, proving that cinema still holds a place in today’s streaming society.

2022’s other top films include two superhero sequels (“Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness” and “Thor: Love and Thunder”), a science fiction blockbuster (“Jurassic World”), and a reimagining of a hero’s origin (“The Batman”). The formula proves true—mass-marketed movies sell, and “Black Panther: Wakanda Forever” will presumably surpass “Top Gun’s” $1.4 billion gross after its November release.

In 1990, the inflation-adjusted average production budget of the top-20 grossing films was $63 million, but in 2019 it ballooned to $141 million. Film researcher Stephen Follows found that a film’s budget has a strong correlation (0.744 Pearson correlation, for you statistical nerds) to its projected gross return. Quite simply, the studios understand that spending money makes money, and mid-budget films don’t fit into this equation.

The industry was starkly different in 2007. Four of the best picture nominees fell into the mid-budget category—“No Country for Old Men” ($25 million), “Atonement” ($30 million), “There Will Be Blood” ($25 million), and “Michael Clayton” ($21 million). Before streaming disrupted entertainment, movies in the $15 to $70 million range showcased creative experimentation.

Sure, 2007 had its big franchises. The top box office performers included “Spiderman 3,” “Shrek the Third,” “Transformers,” “Pirates of the Caribbean: At World’s End,” and “Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix.” Hollywood knew its moneymakers, but they weren’t the only movies getting theatrical releases.

The Academy still prefers historical and social issue dramas over Marvel and DC movies, but today’s Oscar darlings must manage with smaller budgets. Last year’s best picture winner, “Coda,” cost $10 million, while 2021’s winner, “Nomadland,” cost $5 million. Critically praised mid-budget films like “The Power of the Dog” ($35 million), “Mank” ($25 million), and “The Trial of the Chicago 7” ($35 million) got released directly to Netflix. The COVID-19 pandemic impacted those distribution decisions, but the studios clearly lacked faith in their box office potential.

Spike Lee’s “Da 5 Bloods” cost $40 million, and he hoped for an early 2020 theatrical release. But after struggling to secure a deal with a major studio, he had to partner with Netflix. If a celebrated director like Spike Lee can’t find a non-streaming distribution deal, how will anyone make a studio-backed movie that doesn’t feature Thanos or Green Lantern?

Some of the most influential films of the last half-century had medium-sized budgets. “Silence of the Lambs” ($19 million), “Shawshank Redemption” ($25 million), “Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind” ($20 million), and “Raging Bull” ($8 million in 1980, $28 million inflation adjusted) wouldn’t get made today because studio executives would question their box office potential. Mid-budget films don’t have the extravagance of larger-budget movies or the quirky minimalism of independents, but they allow filmmakers to expand their creative pallets. They’ve allowed directors like Paul Thomas Anderson, David O. Russell, and Steven Soderberg to go from scrappy up-and-comers to household names.

Today’s avant-garde dramas and genre-defying comedies materialize as prestige television. In the 90s or 00s, Columbia Pictures might have released a satire about a media mogul passing down his business to his spoiled kids, starring Robert DeNiro as the mogul, with Jake Gyllenhaal, Jennifer Lawrence, and Ed Helms playing the adult children. Instead, we have the hit HBO series “Succession,” with famous producers, an exceptional writing staff, and a B-list cast. If Hollywood-of-old existed in 2022, MGM would release a movie about a young restauranteur trying to keep his debt-riddled family business afloat, creating a realistic portrait of foodie culture while examining themes of addiction and masculinity. Instead, we have Hulu’s series “The Bear.”

No actor has been more vocal about the demise of medium-budget films than Matt Damon. He referred to those $20 million to $70 million movies as his “bread and butter,” and told the New York Times, “You need those roles to develop as an actor and build your career, and those are gone.” Films like “Talented Mr. Ripley” ($40 million), “Invictus” ($55 million), and “The Informant!” ($41 million) would get released as streaming miniseries in today’s entertainment landscape.

Damon believes the ability to penetrate international markets explains why studios prioritize superhero blockbusters. The number of Chinese movie screens has grown from just under 5,000 in 2009 to over 82,000 by 2021. Superhero movies are easily translatable across cultures because of their striking visuals and simplistic plots. Foreign countries might not show interest in a Coen Brothers portrayal of the 1960’s folk music scene or an Adam McKay biopic of a former vice president. The existence of international markets like China, India, South Korea, and Mexico, combined with the ancillary revenue made from merchandising, explains why comic book franchises and action/adventure/fantasy remakes have taken over Hollywood.

Damien Chazelle should be a household name as a prodigal director, the same way the public viewed Quentin Tarantino in the mid-90s and J.J. Abrams in the mid-00s. But the shifting Hollywood landscape has diminished his moviemaking opportunities. His first feature film, “Whiplash,” was met with critical acclaim, and two years later he directed “La La Land” to similar acclaim. Chazelle’s next film, “First Man,” again won over the critics, but only made $107 million on a $59 million budget, and he no longer had a blank check from the studios. Naturally, his next move was Netflix, where he directed two episodes of the show “The Eddy.”

Anytime movies within the $15 million to $70 million range fail, it only gives the studios justification to avoid them. In 2019, Warner Brothers gave “The Kitchen” a $38 million budget. With a stellar cast featuring Melissa McCarthy, Tiffany Haddish, and Elizabeth Moss, this crime drama would have easily made $100 million in the 80s or 90s, but it flopped, grossing only $19 million.

Seth Rogen was once a box office draw with movies like “Knocked Up” ($30 million budget, $219 million gross), “Superbad” ($20 million budget, $170 million gross), and “Neighbors” ($18 million budget, $270 million gross). In 2019, he was given $40 million to make “Long Shot,” and although the reviews were positive, its $53 million gross fell short of studio projections.

The studios can stomach a big-budget superhero/fantasy/remake failure. The confoundingly expensive “Solo: A Star Wars Story” ($275 million budget) was considered a box office flop, but not all flops are the same, and this one was still profitable after grossing $393 million. Marvel lost $100 million on 2019’s “Dark Phoenix,” but when “Avengers: End Game,” “Spiderman: Far from Home,” and “Captain Marvel” each grossed over $1 billion that same year, they offset the box office bomb.

Mid-budget movies aren’t the economic powerhouses they used to be. Legal dramas like “A Few Good Men” ($33 million budget, $243 million gross), coming-of-age dramedies like “Dead Poets Society” ($16.4 million budget, $235 million gross), and romantic comedies like “The Proposal” ($40 million budget, $317 million gross) have migrated from the theater to streaming platforms.

Hollywood’s present-day creative impasse is comparable to its environment during the mid-1960s. The studio system churned out financially successful but creatively uninspiring films, relying on remakes, hit plays, big-budget musicals, and James Bond. The big five studios—Paramount, 20th Century Fox, RKO, Warner Bros, and MGM—didn’t care about the experimentally progressive French and Italian films because they didn’t need to, and the production code limited their ability to address subversive topics. The existing system filled their pockets and cinematic innovation didn’t concern them.

Today’s big five features Disney, Columbia, Universal, Paramount, and Warner Bros. Like the mid-60s, they rely on familiar genres to make money. Today’s social media cancel culture serves as a quasi production code that limits the studios appetite for risk. The big five don’t draw inspiration from ambitious production companies like A24 and Annapurna Pictures, just as the old guard didn’t (initially) borrow from the French New Wave.

The assembly-line style of film production eventually died by the early 70s, as directors like Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, and Francis Ford Coppola sparked a creative revolution, getting increased control over their films without studio interference. To escape this current creative rut, Hollywood must empower a new generation of filmmakers, and it luckily has a whole television industry to steal from.

With inventive comedies like Quinta Brunson’s “Abbott Elementary,” Phoebe Waller Bridge’s “Fleabag,” and Issa Rae’s “Insecure,” TV is showing Hollywood how the showrunner of today is like the director of the 70s. These three, along with Donald Glover, Ryan Murphy, Shonda Rhimes, Vince Gilligan, Kenya Barris, Jen Statsky, and Mindy Kaling are among the most innovative voices in entertainment. For the film industry to be more than a superhero smorgasbord, it must give moviemaking opportunities to these showrunners.

Although this article has exclusively discussed the decline of medium-sized films, there are several examples of mid-budget success stories. 2019’s “Knives Out” made $311 million on a $40 million budget. This whimsical murder mystery with a deep cast and longtime-but-unknown director is the type of film that studios regularly released from 1970 to 2010. “Crazy Rich Asians” ($30 million budget, $238 million gross), “Hustlers” ($20 million budget, $157 million gross), and “Hidden Figures” ($25 million budget, $236 million gross) have proven that mid-budget movies can succeed with the proper backing.

Jordan Peele and Greta Gerwig are two of Hollywood’s most sought-after directors, and they’ve proven the economic upside of mid-budget films. In 2019, Peele’s “Us” made $255 million on a $20 million budget, while Gerwig’s “Little Women” made $218 million on a $40 million budget. Both come from non-traditional backgrounds for directors, as Gerwig was a writer and actress for a decade, while Peele was an improv and sketch comedy performer.

For the studios to produce quality cinema, they must identify and empower creators. While big-budget films attain global popularity and independent films build intimate connections with niche audiences, the mid-budgets are the type of movies that make us fall in love with the movies. Cinema has the power to spotlight social inequities, give voice to the voiceless, and critically engage with antiquated norms. The business of film and the power of film don’t have to be incompatible.

Sources

bigpicturefilmclub.com/did-high-end-tv-replace-the-mid-budget-indie-film/

cnn.com/2022/02/26/entertainment/mid-budget-movie-decline-cec/index.html

collider.com/why-mid-budget-movies-are-important-for-theaters/

economiststalkart.org/2022/02/15/globalization-and-the-rise-of-action-movies-in-hollywood/

mutantreviewersmovies.com/2022/01/15/where-have-all-the-mid-budget-movies-gone/

nytimes.com/2021/07/27/magazine/matt-damon.html

open.lib.umn.edu/mediaandculture/chapter/8-2-the-history-of-movies/

qz.com/1756279/knives-out-is-the-last-of-a-dying-breed-of-mid-budget-movies/

statista.com/statistics/279111/number-of-cinema-screens-in-china/

stephenfollows.com/disappearing-mid-budget-drama-movies/

stephenfollows.com/is-a-movies-box-office-gross-connected-to-its-budget/

thewrap.com/never-mind-avengers-overseas-markets-are-hollywoods-box-office-superheroes-52006/

vanityfair.com/hollywood/2019/05/is-the-mid-budget-movie-an-endangered-species