In Conversation With: Lee Chia-Hua

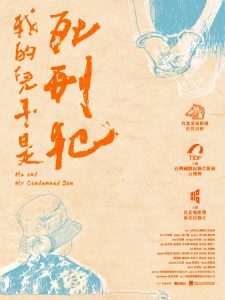

The Independent’s Claire Fairtlough interviewed director Lee Chia-Hua about his documentary, “Me and My Condemned Son.” The documentary focuses on three prisoners in Taiwan who have been sentenced to death: one who is still serving his sentence, one who has taken his own life, and one who has already been executed. The documentary follows these prisoners and their family members as they try to navigate their future. The documentary consists of raw footage and personal interviews, while raising important questions about the future of Taiwan’s judicial system. Hua navigates the controversy that surrounds the death penalty with empathy and compassion, while diving deep into the history of capital punishment.

Fairtlough: When I was doing research on your film, it was such a moving and intense documentary. What made you want to be a filmmaker, specifically documentary. What excites you about documentaries?

Chia-Hua : It’s a long story…maybe too long. I never intended to make documentaries. I just wanted to tell stories. I grew up watching Hollywood movies and originally wanted to just make drama and feature films. I went to get a degree in documentary making and it’s been my path since then. I’m still exploring opportunities in making drama and feature films, but I’ve found that making documentaries has the most opportunities for me at the moment.

Fairtlough: The cinematography is beautiful and the editing is incredibly seamless. What style choices did you take into consideration in making a documentary with themes and topics as heavy as this?

Chia-Hua: This is also a hard question! I really have to thank my production team. It’s a very different process working with documentary teams than with feature films. I’m used to modifying and adapting my way of working throughout the whole production. I just go with where the story is taking me, and I want my style to reflect that. This took me four years to film, so I had a lot of footage and it ended up taking a completely different direction than I originally intended. I had to consider the footage that I was actually able to get and use. Also, can I really use this? It came down to ethics. I had to consider how it would impact people who are still around, and what other people will think of them for telling their stories. It became an ethical issue for me. I ended up getting controversial and highly debated footage, but I decided not to include it for these reasons. Even though some people would think that if I used this footage it would be a more interesting story. I didn’t want it to have a negative impact on other people’s lives.

I really wanted to focus on the people instead of trying to make the most shocking, media-thirsty documentary as I could. I don’t want this to be the outcome. I’m glad that my production team helped me with this.

I do have some political ambition when shooting this. I wanted people to talk about the death penalty as an issue. My goal of cinematography was to get people to pay attention, and hopefully incorporate these discussions in their own life.

Fairtlough: I think it’s admirable that you chose to tell this story this way, instead of falling into the attention that true crime media gets. I’m curious, in Taiwan, what has the response been for you making this documentary?

Chia-Hua: The popular opinion in Taiwan towards prisoners could have more empathy. There is a cultural difference here, there is a cultural origin. People in Taiwan deeply believe in karma. They really believe in the consequences of your actions. The concept of ‘eye for an eye’ is more accepted in Taiwan than what I’ve observed in the United States. Every year there is a survey about the death penalty in Taiwain, and for the past ten years the people who support the death penalty are 80%. There is a strong opinion that is pro-death penalty.

I got a lot of criticism while I was making this documentary. Questions like “Why are you speaking up for these prisoners?” And comments telling me that they deserve to die and I shouldn’t be making this film. The worst comment I got was, “Wait until someone is murdered in your family, then you have the right to make this film.” It can be a lot, but I was prepared for this while making the film. I had some more civil conversations about people who disagreed with me, which is overall the goal that I want to achieve. I want to develop interpersonal connections with others, and help them understand my opinion. At the end of the day, opinions are better than no opinions. At least in that way, they care enough about the topic to discuss it. What would be worse, is if no one cared about the death penalty at all.

In the beginning, I was very sensitive to these comments. But now, I recognize why people feel so supportive of the death penalty is because they feel a sense of justice. This raises the question of how we achieve actual justice.

Fairtlough: What does Crack and Light Mean to You?

Chia-Hua: I was nervous when I realized that this was the theme of the festival. It seems to be a very stationary theme, but actually it holds so much meaning. To me, it means something to break through. I know that my work is controversial, so I wondered what my film showing in Boston would do in regards to public opinion in the United States. I was unsure of how it would be received. I was nervous if my documentary would hold up to this theme.

Fairtlough: It absolutely does!

Chia-Hua: Thank you, thank you!

Fairtlough: Finally, what does justice mean to you? I know that this is a big question, but I’m just curious to what intention you had with telling this story in particular.

Chia-Hua: That’s a huge question! There’s a lot to answer here, especially because it raises a big question about ethics. Honestly, up until I was 30, I was very supportive of the death penalty. I was asked to do a project around a prisoner who was wrongfully convicted for a crime. In order to complete this project, I had to do a lot of homework. The prisoner was convicted with a death sentence, and the more I learned about this prisoner’s story, the more questions I had. The more I talked with this prisoner, my views on justice completely changed. I thought that the death penalty brought justice. I thought that it inhibited crime and that it was an efficient way of running the judicial system. I thought that it helped the victims. I realized that absolutely none of this was true, and my opinions weren’t valid.

At the end of the day, I supported the death penalty because I didn’t understand it. This documentary is my reconciliation with my past views. It’s for an audience who held many of my pre-held beliefs on justice, and really consider what the purpose and goal of the death penalty is. My intention is for people to be more educated before they make a judgment call like this. I really want to encourage people to sit down and have conversations about what is the purpose and goal of the death penalty is.

I want a justice system that has practical solutions to deep social problems, not just one that’s angry with what someone has done. Even at an individual level, the state should be like a guardian. The state should be the one who keeps rationality, instead of emulating what the individual wants. Instead, it should be a system that regulates order. If I as an individual can’t carry out my own justice through killing someone, why should the legal system be able to? I think that all this does is create a vicious cycle.