New York Jewish Film Festival, January 12–23

With antisemitism on the rise worldwide, the 32nd NYJFF responds with 5 powerful dramas

The cautionary alerts are everywhere throughout Manhattan. At the Center for Jewish History on West 16th just off Fifth Avenue, president Gavriel Rosenfeld writes that to understand “growing antisemitic threats facing American Jews, examining the past is indispensable for understanding the present.” At Bloomberg Philanthropies, former NYC mayor Mike Bloomberg introduced showings of Arthur Miller’s Focus with William H. Macy and Laura Dern. The movie is a taut, suspenseful antisemitism drama set in Brooklyn during World War II, which Bloomberg produced in 2000 prior to his first mayoral run. At the Museum of Jewish Heritage, historian Steven J Ross uses his book Hitler in Los Angeles to explain how Hollywood Jews uncovered 1930s and 40s plots aimed at attracting international attention to the Nazi causes which sparked pogroms across America. At NYC’s newest movie theater, DCTV Firehouse Cinema, Filmmakers for the Prosecution (newly titled) finally opened on January 27, almost a year to the day after its showing at the 2022 New York Jewish Film Festival (and our lead review in The Independent) on how motion pictures were used to convict Nazis at the first Nuremberg Trial. And at the Anti-Defamation League, the Shine A Light initiative continues cooperating with top companies like L’Oreal, Unilever, ComcastNBCUniversal, UPS and Etsy that have pledged to integrate antisemitism education into their training and Jewish employee resource groups.

The 32nd New York Jewish Film Festival, showcasing 21 features and 8 shorts, just concluded at Lincoln Center’s Walter Reade Theater. The Jewish Museum and Film at Lincoln Center, its co-sponsors, asked outlets to withhold long-form reviews on nearly all major films during the run of the festival. (These embargoes, which The Independent dutifully respects, are becoming more widespread as huge streaming services control the distribution, and thus the destinies, of many independent dramas and documentaries.) One of NYJFF’s most consistent themes through decades of programming has been to ‘Never Forget’ the unspeakable horrors of the Holocaust. Its urgency today as a response to increasing antisemitism has never been more important. And so NYJFF curated no less than five powerful–and powerfully different–antisemitism dramas. None were spotlighted as the Opening Night, Centerpiece or Closing Night attractions. But all five are critic’s choices, each worthy of your closest attention and consideration. All have first-rate distributors so there will be ample opportunities for viewing. Also included are shout-out reviews on two shorts themed to another kind of hurtful discrimination that’s ever-so-slowly being erased.

June Zero: Jake Paltrow: USA/Israel: 2022: 105 minutes

The fate of Adolf Eichmann, the Nazi mastermind behind the deportation of millions of Jews to death camps during the second World War, has been explored sequentially through three key movies starting a decade ago. Paltrow’s June Zero is the third and last. It’ll be helpful to summarize the first two, The People Vs. Fritz Bauer and Hannah Arendt.

In 1957, Eichmann, knowing he’d be charged as a war criminal if he was captured, fled to Buenos Aires where he changed his name and disguised himself as a worker at the Mercedes Benz plant. A Jewish immigrant recognized him and through a network of letters reached Fritz Bauer, the youngest district judge in Germany. Bauer was committed to bringing the Nazi regime to trial, despite a German high command that wanted to forget the past. Bauer contacted Mossad and Shin Bet, the elite Israel Intelligence services, which succeeded in kidnapping Eichmann and flying him to Israel. He was then moved to Frankfurt, where other officers of the SS Garrison were being held. In the unprecedented Auschwitz trials, most of those men were found guilty (but served only brief sentences) in The People vs. Fritz Bauer, a fine 2015 drama distributed by Cohen Media Group and Charles Cohen, who can show it whenever he wishes at his four-screen Quad Cinema in Manhattan.

Three years earlier, director Margarethe von Trotta picked up the thread in Hannah Arendt, a vivid docudrama in which Barbara Sukowa played the controversial Manhattan journalist who covered the Eichmann trial. Actual black-and-white clips of the trial are intercut with the Arendt drama in color. We watch Eichmann concoct his defense as a minion simply obeying orders, so far down the chain of command in arranging the transport of Jews to Auschwitz and other concentration camps as to appear inconsequential. The trial lasted eight months, and 99 Holocaust survivors testified; Eichmann was found guilty and sentenced to hang. Arendt wrote a book, Eichmann on Trial: A Report on the Banality of Evil, in which her main thesis is that evil was the ultimate act of thoughtlessness. Arendt’s stance has not played well through the Jewish community then or now, though her tenure as a professor at Manhattan’s New School was never threatened. The picture played without incident at NYJFF in 2013 and was fully reviewed in The Independent.

Which brings us to Jake Paltrow and June Zero. The title refers to a day in 1961 when Eichmann was hanged and cremated. If you glance up at the scene still, you see Israeli schoolkids perusing a tabloid which alternates bathing beauties with anticipation of the verdict (“Should Eichmann Be Hanged?”), except this street rag forgets to print its June date at the top of its pages–thus the title. Paltrow’s fanciful concept, with co-writer Tom Shoval, is to have the paper grabbed by a Libyan 12-year-old who’ll come to play an all-important role in the events that take place. As it turns out, the boy–David, played by Noam Ovadia, a non-professional, cast on location in Israel–turns out to be the irresistible lead who drives the movie in surprisingly engaging (and often amusing) ways. Sometimes luck smiles on directors who don’t understand Hebrew but are shooting in Hebrew, directing a kid who’s never acted, in Super 16mm, a long long way from New York City… all in the worst days of COVID’s spread.

David, who’s a recent immigrant with his family, finds work at a scrap metal factory that builds, among other things, ovens for kibbutzim. The kid’s a go-getter who’s a fast learner. When the factory is tasked by the Israeli government to build an oven for Eichmann’s cremation, immediately after his hanging, David’s all eyes. At this point, the movie’s focus shifts to the Moroccan guard Hayim, a nervously affable Yoav Levi, whose job is to mind the prisoner and keep him safe from assassins, like a fake barber who looks ready to slit the Nazi’s throat. The other major character introduced, Micha, played by a gaunt and effective Tom Hagi, is one of the 99 Auschwitz survivors. He delivers a monologue to camera that feels grim enough to have been taken from actual trial transcripts. Micha is the movie’s moral conscience.

When the oven is finished the day before the cremation, it’s tested on a dead sheep, which emerges a smelly carcass. “Unless the government wants Eichmann medium rare, we’re going to need a bigger burner,” is the tech opinion. The only overnight option is to swipe one from a bigger oven at a competitor’s factory. The facility has a high fence with an opening only a skinny kid could fit through. Ah!

June Zero has a ragged continuity, but none of that matters because the plot–true or invented, inspired by real events or the screenwriters’ imaginations–never flags. Paltrow, who co-directed the De Palma documentary as well as directing his older sister Gwyneth in The Good Night, keeps inventing one surprise after another. He’s like the guy in the circus who balances pie plates up on sticks–if one plate falls, they can all tumble down. But the plates keep spinning. His cast feels with him. So does his producer Oren Moverman, a veteran pro who may have talked Jake into changing his original script title, The Oven, and maybe convinced him to shoot on location using 16mm which gives the picture a true-to-’60s-grain. Paltrow’s final surprise is a shrewd coda ending which brings an ironic and unexpected closure to that missing June date. You’ll approve it all.

Shttl: Ady Walter: Ukraine/France: 2022: 114 minutes

Writer/director Walter’s ambitious and dangerous premise was to erect an entire Yiddish speaking Jewish settlement north of Kyiv, Ukraine.

That’s the Kyiv we read about and watch being battered every day by Russia. Except Walter’s 20 huts, communal residences, and a large hand-painted synagogue were built to 1941 specifications. The director wrote his drama to take place on the evening and morning of June 22, 1941, when a similar shtetl was attacked and destroyed by Nazi Germany’s 17th Wehrmacht Army. The “Sovietization” of this shtetl took place on the same land—across a river from eastern Poland, which was already occupied in ‘41 by the Nazis.

Using a Ukrainian crew and a huge international cast, Walter envisioned a two-hour exploration of the village with a roving camera, recreating the last hopes and dreams of an agitated but peaceful community about to be sacked and destroyed. Walter also elected to rehearse and shoot his bold concept in long, unbroken takes. (Not dissimilar to Sam Mendes’ recent war drama 1917 and echoing back to Alfred Hitchcock’s 1948 Rope). On top of that, he wanted to experiment with switching certain scenes from black-and-white, capturing gritty community life then, to brilliant color, suggesting a more optimistic day for the characters in a future they’d never see.

The director’s plan after filming was to donate his entire village set, in all its meticulously restored accuracy, to the Ukrainian government, as a permanent educational exhibit. But shortly after filming wrapped late last summer, Russian bombs, missiles and land mines ruined his movie village…just as Nazi Germany’s unprecedented invasion ruined Jewish village life in 1941. Walter has removed the letter ‘e’ in the movie’s title from the conventional spelling of “shtetl,” signaling its permanent loss up on the theater screen as well as in Ukraine’s continuing war today with Russia.

Chances are you won’t recall a film drama with this set of then-as-now ironies in your entire moviegoing life. And if you know the backstory walking in–and now you do– you’ll be hooked from the get-go.

The shtetl’s residents are locked into traditions nearly every member affirms and abides by. Their village has been infiltrated by Russian propagandists it doggedly refuses to recognize or even acknowledge. Then its strict adherence to Torah teaching is further disrupted by the arrival from Kiev (as it was then called) of Mendele, played by Moshe Lobel, a robust youth with all the gangly fervor of a young Jimmy Stewart and a budding filmmaker. Oh my God, a movie maker. He grew up in the village, admired and well liked, and then, like anyone else who leaves this fold, ‘lost his way.’ Like the young Steven Spielberg in The Fabelmans, he has the intelligence and learned knowledge to tell a hundred stories and not just the one everyone studies every day. Mendele’s come home with a Ukrane pal, Demyun (Petro Nivouskiy), to visit his father and maybe steal away a former love, Yura (Anisia Stasevich). She’s a winsome and fiery young woman who’s been persuaded against her will to marry a prickly butcher’s son who’s preparing to succeed the present rebbe, played by a majestic Saul Rubinek. It’s an easily understood setup, and the film’s major issue for its first 100 minutes or so, as the day slips away into evening, is how much pushback Mendele will encounter. Oh, more than you can imagine.

The village schoolteacher thinks Mendele’s come to make trouble. His father mourns how his wife, now passed, abandoned their home to pursue outside interests–and that their son’s “magic is off limits to us.” Any number of villagers call him a charlatan who’ll “soon have everyone speaking Russian” and will bring down the community. And the venerable rebbe wonders whether Mendele is making “genius–or gentile–movies.” He lectures Mendele that the one movie he ventured out to see, Tarzan, provoked emotions he simply couldn’t handle. Mendele decides he’d better figure a way to smuggle Yura out of town fast. And, with Demyun in tow, he does. But the German Army is already waiting for them.

As in the Holocaust drama Son of Saul, director Walter’s camera never stops flanking its lead character. Lobel’s earnest performance has to hold you in thrall for nearly two hours, and it does. (Full credit to steadicam operator William Oger, whose lensing is flawlessly smooth.) That said, there’s a constraining novelty in watching movies like 1917 and Bi Gan’s Kaili Blues and Long Day’s Journey Into Night, with their relentless camera movements that never change a fixed POV or appear to cut. Put it this way: with unbroken takes, it’s impossible to forget you’re watching a movie that’s been staged and choreographed to the nth degree. As Hitchcock was the first to admit, it’s an original gimmick and it’s a marvel to see it used so well in a debut narrative feature out of Ukraine… but at the end of the day it’s still a gimmick.

With that reservation noted, the Ukraine’s Shttl can join a pantheon of superior Shoah narrative dramas that cast–in Annette Insdorf’s words–indelible shadows.

Schachten–A Retribution: Thomas Roth: Austria: 2022: 110 minutes

The most interesting character to slip in and out of Thomas Roth’s timely drama, whenever evil events threaten to overwhelm not just the characters but the movie itself, is Simon Wiesenthal. That’s the Simon Wiesenthal. The name is known to Jews worldwide. Roth conceives him as a calm philosophical precisionist, acted with suitable gravitas by a persuasive Christian Berkel.

Wiesenthal was a Holocaust survivor who dedicated his life to alerting the world to find and prosecute Nazis who evaded justice. His role in this movie is to interpret and summarize events we’re watching, and to subtly strategize the correct and incorrect ways for the characters we care about to respond to virulent antisemitism. (Wiesenthal’s missions have been carried on since 1977 by dedicated leadership and 400,000 family members of Simon Wiesenthal Centers in seven major cities, by their Museum of Tolerance in Jerusalem, and by their Moriah Films which has produced 17 Holocaust documentaries.)

Roth’s story is laid out as plainly and bluntly as his title. Schachten in Yiddish means slaughter; Retribution here means revenge. A young businessman in 1962 Vienna, Victor (Jeff Wilbusch, guileless and effective) is haunted by dreams of his mother, sister and grandparents being seized or murdered before his 8-year-old eyes in snowy Austrian forests. Wiesenthal explains to Victor how Eichmann’s trial was the bitter tip of a Nazi iceberg that has migrated to Vienna–hundreds of outwardly reputable merchants, lawyers, teachers, even ministers who were all Hitler’s ministers of death. Wiesenthal’s Jewish Historical Documentation Center in Linz was already known as the leading post-War Nazi hunter. Wiesenthal has police protection for his own daughter, as well as an Israeli Mossod agent tucked away for added security.

Victor’s dad Paul (Michael Abandroth), who witnessed atrocities at the Mauthausen camp in Austria near Linz, is called to testify at the trial of camp commandant Gogl (Paulus Manker, memorable In The People vs. Fritz Bauer and even stronger here). The churlish, snarly Nazi monster is now a demure middle school head teacher at a private girls’ school. He denies all in a courtroom packed with Nazi sympathizers, and walks. Adding to Victor’s mounting frustrations is a sexual relationship he’s started with a very Catholic girl, Anna (Miriam Fussenegger), both of whose parents turn out to abhor Jews. Victor keeps flashing back to his own narrow escape in the snow. Wiesenthal works overtime counseling Victor, after his dad’s passing, on ways to achieve a measure of justice without violence. The two of them engineer a fitting retribution for Gogl.

Roth has mounted a confident, assured suspense drama, elegantly filmed and acted by a splendid ensemble that keeps you pinned to its pulse. It honors the legacy of Simon Wiesenthal, a tireless activist who nailed Josef Mengele, the doctor of death at Auschwitz, and even arrested the man who arrested Anne Frank.

Farewell, Mr. Haffmann: Fred Cavaye: France: 2021: 116 minutes

Cavaye’s grimly satisfying drama, a different kind of revenge tale, shares one inescapable similarity with Anne Frank’s diary.

Anne received a 13th birthday notebook in June 1942, in which she began writing The Diary of a Young Girl that December. Her entries would continue to March, 1944, while hiding with seven other members of two Jewish families. Their home was what she called a ‘secret annex’ on two upper floors of a building on the Prinsengracht canal in Amsterdam. Not that it matters–but in a movie review it always matters–George Stevens’ 1950 filming of Anne’s diary won Oscars for cinematography, art direction and supporting actress.

Farewell, Mr. Haffmann is set in Paris during its 1941 Nazi occupation. The takeover will force the Jewish designer/owner of a cosmopolitan jewelry shop, Joseph Haffmann (Daniel Auteuil, in a towering performance), to take refuge in his own cellar through much of the movie. When his wife and children are safely out of Paris, Joseph tasks his assistant, Francois (Gilles Lellouche), who appears respectfully loyal, to run the business. He even deeds him legal ownership of the shop. Joseph sees his young protégé has promise as a crafter of fine jewelry. Francois is eager to start a family with his adoring wife Blanche (Sara Giraudeau), who works as a laundress, ironing on her feet all day. She hasn’t been able to conceive, which frustrates Francois. Neither she nor her husband are Jewish.

Though it shifts now and then to other locations and characters (mainly Nazi officers who’ve taken a shine to their jeweler’s work), Farewell Mr. Haffmann is essentially a three character movie in a storefront and a basement. It’s a good thing Auteuil, Lellouche and Giraudeau are each at the top of their games, for they have to bend to a plot twist that would sink lesser movies.

As more and more surrounding Jewish merchants are seized and deported, Joseph’s business becomes dependent on officers of the occupying German force, who have an eye (and the funds) for expensive pins and necklaces they’ll gift their mistresses. Joseph writes his family loving letters that assure them of his continuing safety, This is risky but Francois says he’ll mail them, and never does. The inventory of pieces Joseph’s made is running out, and Francois knows he doesn’t have Joseph’s skills. The Nazis demand top quality pieces assuming Francois made them, and that as the shop’s sole owner/jeweler, he’ll keep producing them.

And so Francois offers Daniel (and Blanche) a true devil’s bargain: He says he’ll keep risking his life posting those letters to Daniel’s family, if Daniel sleeps with his wife long enough to get her pregnant.

It’s a desperation premise in a desperate time. It raises the eternal moral dilemma of what you’d do to stay alive if you were trapped in wartime. And to the immense credit of Daniel, Sara and Gilles who inhabit their roles fully, you may buy it. This viewer did. Blanche does, at first reluctantly, in part because she realizes her only ticket out of ironing Nazi laundry forever is to keep her husband’s lie alive, that the invaders believe he’s the one high end jewelry designer and merchant left in all of Paris. She also tolerates her husband’s demand that Daniel restart crafting superior jewelry for the Nazis down in the basement. But when Daniel recognizes the gems he’s being given to re-set are stolen from pieces owned by deported Jewish families, he refuses. It looks like all three characters will be doomed.

Wait, wait–the movie won’t end here. There’s another twist (no more reveals) in Farewell Mr. Hoffmann, who you assume will be removed when he’s inevitably discovered, just as Anne Frank was. But that’s not how writer/director Cavaye sees it. Trust that he’s conceived a gem of a conclusion that’s both unexpected and appreciated.

March ‘68: Krzysztof Lang: Poland: 2022: 115 minutes

Look at Hania and Janek, pictured together. They’re as appealing a young student couple as ever attended Warsaw’s State School in the late1960s. She’s a theater major, he’s an engineering kid who likes the arts. They meet cute, watch a stirring play on Russian oppression (Adam Mickiewicz’s 19th century Forefathers’ Eve), chase around while black-and-white clips show Warsaw citizens leading busy lives scored to tunes like “Route 66” and “Choo Choo Boogie.” The young adults are in bed together in less than 25 minutes running time. The median age of the entire Polish population in 1968 was 27. Could this be the feel-good Polish rom-com you’ve long awaited?

But director Lang is already dropping hints of darkness to come, starting with archival photographs of school children who’ll vanish from Poland along with thousands of other Jewish family members in his chilling docudrama. At the play, we eavesdrop on uniformed Russian Communist officers in the audience, muttering their disapproval. Then we catch snatches of Radio Free Europe reporting the severance of relations between Poland and Israel. When Janek telephones Hania at her parents’ pleasant home to chat, her father, who’s a security officer in the Gomułka regime, is listening in, and has the call traced. He wants to learn all about the boy’s parents.

What he learns is what he suspects: Janek’s dad’s name is not Bielski but Gutman, and he’s already been fired as a neurosurgeon, a Zionist who dared to organize a hospital party celebrating Israel’s victory in its Six Day War against Syria, Jordan and Egypt. His wife is also about to lose her upper level publishing job for signing an author in disfavor with the government. This Is another post-war family with a slim financial cushion. But the country’s Communist dictatorship doesn’t just want Jews out of work; it wants them out of Poland.

Meanwhile, Hania and Janek are bravely attending student rallies to protest the shutdown of its National Theater. They escape police clubs at one but Janek is severely beaten with batons during the second, and Hania is arrested and interrogated. The police dutifully return the girl to her parents, but even her father will find himself sidelined and probably retired for not being able to “discipline his own child.”

Vanessa Aleksander and Ignacy Liss play the student couple with passion and zeal. Their parents–Ireneusz Czop, Edyta Olszowka, Mariusz Bonaszewski and Anna Radwan–are the kind of energized and committed cast one can watch forever in the best of European cinema. Lang’s drama is the cinematic link to Lech Walesa and the birth of the Solidarity Revolution, fused by Jewish Zionists and others labeled as ‘firebrands’ and ‘revisionist intelligentsia’.

Like Shttl, Farewell Mr. Haffmann and Schachten–A Retribution, Lang’s skillfully crafted drama will receive robust distribution via Menemsha. And the most meaningful endorsement comes from a ticket buyer who viewed it recently at the Jewish Cinematheque. “No matter how many times I may have told my wife and sons and many friends, I never felt words alone presented the real picture,” he writes. “March ‘68 accurately reflects one of the most important periods in the life of my family.” A husband and father who grew up in Warsaw, he remembers being one of 13,000 Jews, “the last remnants of the community that numbered 3.3 million before the Holocaust,” expelled from their own homeland.

The message of these five motion pictures themed to antisemitism, honored by The Jewish Museum and Film at Lincoln Center, cannot be repeated too often in these threatening times: Never Again.

Two win-win shorts against a different kind of discrimination

NYJFF, like other Manhattan festivals, now curates outstanding shorts from throughout the world. The Tribeca Festival’s curator of shorts, Sharon Badal, started this back in 2002, and The Independent has been the one film journal long-reviewing the best of NYC festival shorts for over a decade. This fest edition yielded not one but two superlative short films representing victories for the LGBT and especially the trans community. Discrimination over gender identity affects all ages, and artistic victories over that discrimination, of any length, are causes for celebration.

Make Me A King: Sofia Olins: United Kingdom: 2021: 16 minutes

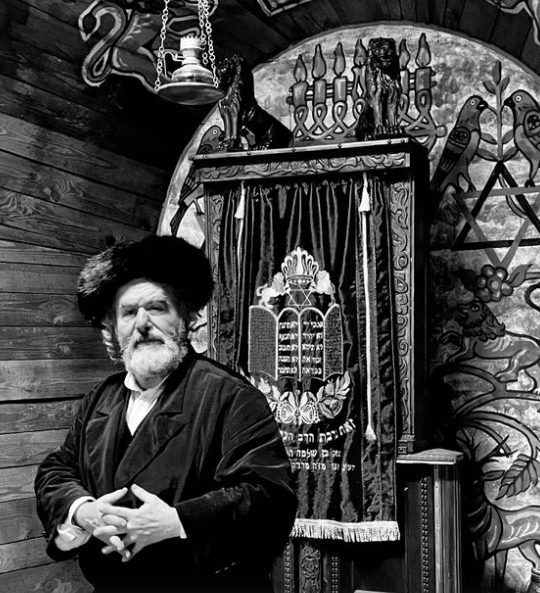

Pepi Littman, pictured in full regalia, was the key cross-dressing drag performer in Yiddish theater during the 1920s. She bears a certain kinship with Sophie Tucker, “the last of the red hot mamas,” who was America’s most popular nightclub singer during the wartime years and post-war eras. Both women were married and teased live audiences with their sexuality–Sophie in bejeweled gowns playing to white glove swells, Pepi with her huskier busker growl who talked/sang in European vaudeville venues. (Another difference was that Sophie fearlessly appeared in public with any number of female lovers, who the world assumed were straight assistants.) It’s not impossible that Sophie, in her salad days. may have seen and studied Pepi’s occasional appearances in Manhattan. Ari (Libby Mai), the youth in in makeup, pictured next to Pepi and gazing longingly up, aspires to be the next drag king. Ari is celebrating a 16th birthday.

Sofia Olins’ wise and compassionate bow to the LGBT community begins with Ari taping her upper chest at home, and is spotted by her Jewish dad, who takes in this wardrobing moment with disbelieving eyes. On stage before an enthusiastic audience, perhaps like her dad–who the film hints may have once been a song-and-dance man himself–Ari kills it. Her mom sits in the audience, watching like a stone. Over lunch she presents Ari with an expensive Jewish symbol, and her son tries to reciprocate with what looks like a mix tape of his recordings. Mom walks away. But that night Ari and her performing mates journey to her London home. Outside, they begin singing “Tumbalalaika,” a Klezmer favorite. The Yiddish melody stirs the parents to their door, then out onto the lawn. Its lyric “a heart can yearn, and cry without tears” begins to magically heal the hurt between parent and teen.

Mx. Lai is one of those rare young talents the camera loves to pieces. The transformation to Pepi happens in a flash. This is one soulful piece of art.

My Parent: Neal Hannah Saidiner: USA: 2021: 9 minutes

What runs through a woman’s mind while she’s transitioning into a man? Hannah Saidiner, a CalArts major in Experimental Animation, asks her 64-year-old dad. Hannah recorded a conversation about her changing relationship with dad. Then she animated it. The viewer has to imagine what they’d look like in real life, and fluid, undulating drawings can resemble a lot of real people. Art directors often turn to animation if they want to persuade the viewer to affirm complex situations. Drawings don’t disguise reality, but they can simplify and soften reality.

Sometimes we watch Neal braiding Hannah’s hair, or Hannah giving Neal a haircut, or we’re watching moving vans loading and unloading furniture, or we’re looking at Neal’s undulating face, or his ID card that now reads “Neal” instead of “Nina,” which sometimes confuses people when Neal needs to display an ID.

Most of the comments are Neal’s, and it’s probably useful to let him speak for himself in these 11 excerpted comments. Creatively as well as emotionally, what this dad says in the animation flow demonstrates how life changes, in small wondrous ways as well as large ones, sometimes before our very eyes:

“I don’t like guys with beards, and here I am with a beard.”

“My cliche is, I make a great man, because I’ve been a wo-man.” “

I’m still not crazy about most men.”

“I tend to like woman who are lesbians…Will it shorten my ability for a relationship?”

“I didn’t want to lose your mom, because she really liked me Butch–black boots, jeans.”

“Not telling you directly was like not telling myself for all those years.”

“I thought maybe we did communicate, maybe not as well as you would have liked.”

“The top surgery was the first step into admitting I was going to go into full transition.”

“I don’t feel ready to go through phalloplasty.”

“I had to decide whether I wanted to be N-e-i-l, or N-e-a-l, And I didn’t want to be Neil Diamond.”

“I’ll always be your mama.”

This concludes critic’s choices. Watch for Brokaw’s picks in Rendez-Vous with French Cinema, March 2-12.

Regions: New York City