New York Film Festival September 29–October 13

In seasons of brutal climate change, New York’s passion for big screen cinema continues undiminished

Film at Lincoln Center knows its audiences. Christian Petzold’s Afire (2023), a German drama of wildfires setting an entire forest ablaze, trapping a quartet of young vacationers, rolled onto Manhattan screens at a downtown festival June 8. One day before, Canadian wildfires turned New York’s skies orange, then nearly black. Mayor Eric Adams walked outside and said “What the hell is this?” The city’s Air Quality index shot up to 484, just shy of a scale-busting 500. Millions of residents made their way through what became the world’s worst air. Petzold’s movie instantly caught moviegoers’ attention. Afire became the summer season’s newest and longest running indie hit, enjoying a seven week holdover at the Munroe theaters on West 65th Street, right up to when FLC launched its 61st New York Film Festival.

Look at the photo. Opening Night capped the seventh wettest day ever recorded in New York City since 1869. Subways flooded and water rose up on sidewalks to the top of bus shelter benches (shown above). But cinephiles somehow muddled through to Alice Tully Hall before the lights went down, for the sold out Opening Night premiere of Todd Haynes’ May December, These are not stay-at-home, watch-it-on-subscription patrons, even though Netflix acquired the picture and with Campari® welcomed Opening Night celebrants to a soggy Central Park afterparty. These are what we used to call movie nuts and now proclaim at cinema saviors.

In its 64-page program, NYFF Artistic Director Dennis Lim also acknowledged “our incomparable audience, whose curiosity and engagement are so vital to the festival experience.” Who else would come out to see 110 films from 45 countries over 17 days? There’s been a sense since 1963 that NYFF curates and showcases dramas and documentaries you may not see anywhere else on a big screen, ever. This viewer has always looked to NYFF for cinematic wild cards that, as Milton Glaser remarked, “inform and delight” like no other movies on earth. Is it worth the slog through often drenched, often overheated, COVID-ridden streets? Even with industry strikes preventing marquee stars from walking red carpets? Even with Apple, its producer, accepting an invite onto the Main Slate and then nixing a showing of Killers of the Flower Moon, maybe 2023’s most distinguished American masterpiece by hometown boys Martin Scorsese and Robert De Niro? (Sigh.) Even with all that.

This NYFF was bursting with little feats and treats, some even free like NYFF Talks. Among the scheduled speakers: poet/activist Nikki Giovanni, actor Sandra Hüller, directors Todd Haynes, Annie Baker, Raven Jackson, Rosine Mbakam, Frederick Wiseman, Kleber Mendonça Filho, Paul B. Preciado, Wang Bing, Eduardo Williams, Nancy Savoca, and Joanna Arnow; editors Sandra Adair and Jonathan Alberts; plus journalists Devika Girish and Clilnton Krute (both FLC staff), Molly Haskell, Adam Nayman, Kelli Weston, Anne Thompson, and Ryan Lattanzio.

The festival also announced 16 new participants in its 2023 FLC Artists Academy and FLC Critics Academy. These programs have supported over 200 underrepresented voices—the next generation of film artists and film journalists—and foster a film culture that embraces diverse storytelling and viewpoints. Intensive three day workshops were held during the fest. Panels, case studies, roundtable discussions and networking opportunities focused on career development and strategies for making a sustainable living as a filmmaker or film critic.

NYFF continued offering select partner screenings in all five boroughs of New York City, including Alamo Drafthouse Cinema in Staten Island, BAM (Brooklyn Academy of Music), Bronx Museum of the Arts, Maysles Documentary Center in Harlem, and the Museum of the Moving Image in Queens.

Here are Critic’s Choices in narrative dramas and documentaries:

Orlando: My Political Biography; Paul B. Preciado; France; 2023; 103 minutes

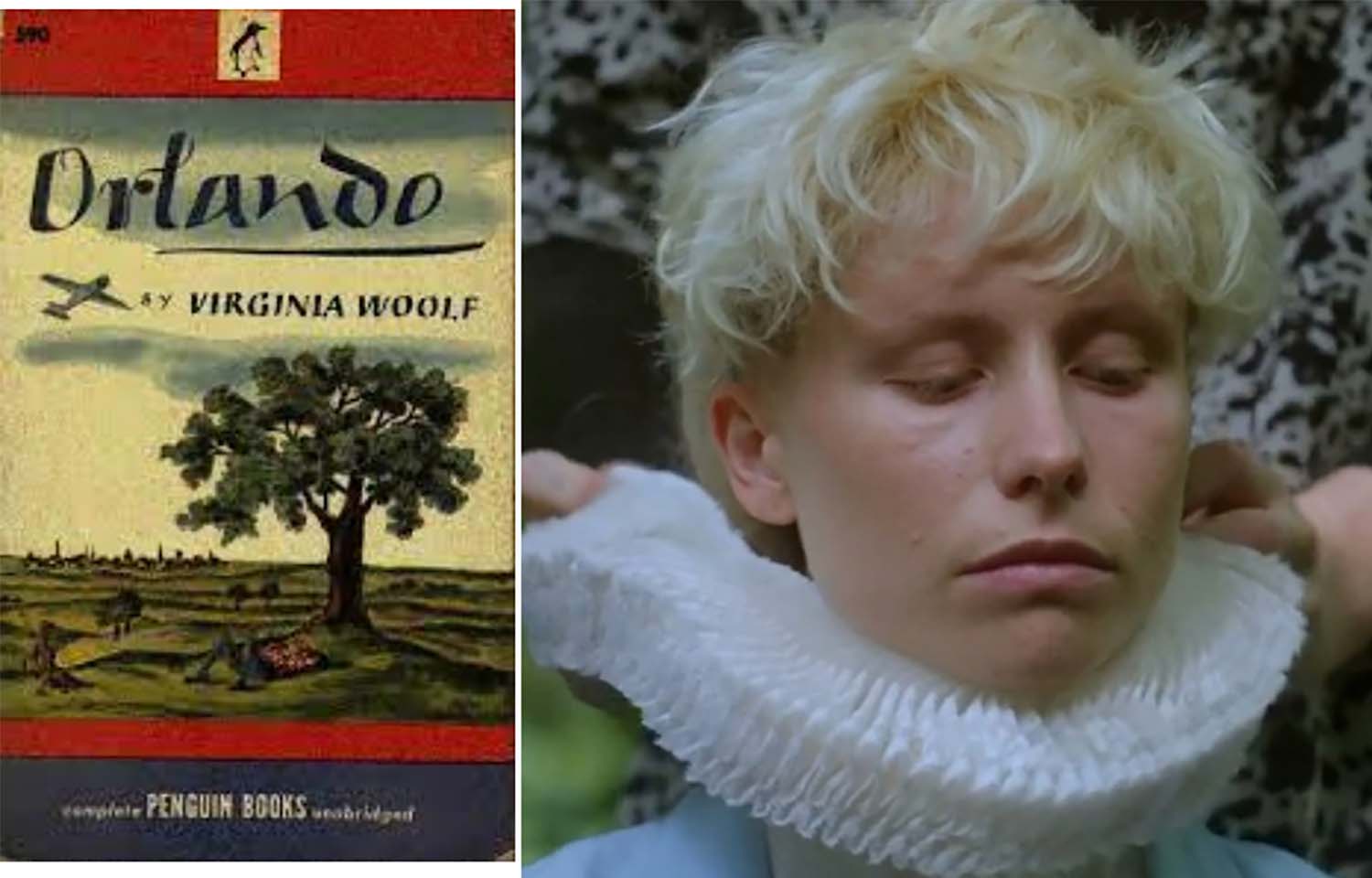

The novel and its author. Our lead photo shows the first American appearance of Virginia Woolf’s Orlando in paperback. Chances are you’ve never seen it. Penguin published it in 1946 at 25 cents, the price of all paperbacks starting in 1939. It had one printing which didn’t produce a second, and publishers obviously concluded Woolf’s work had no commercial potential, since no titles of hers would again appear at a quarter until the 1960s.

Homeschooled, Virginia married Leonard Woolf, a journalist and literary critic, in 1912. Together they founded an imprint that published T.S. Eliot, Katherine Mansfield, and E.M.Forster, as well as her own works. Orlando concludes in 1928, the same year as its hardcover premiere (and also the same year as Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness, the first lesbian novel). Orlando can be heralded as the first transgender novel. Woolf dedicated it to Vita Sackville-West, her lover for three years, who often cross-dressed and preferred the name Julian. If the world had read Orlando, there would already be cries for its removal from public libraries, which would immediately boost its popularity as a dreaded Banned Book.

The cover painting is by George Salter, a classy illustrator of the era. It shows a plane in flight, passing over a dominant oak tree (a recurring symbol through four centuries) which Orlando, having metamorphosed into a woman, will spot and then reunite with the sea captain she’s wed. Illustrators in the 40s often read the novels they interpreted; they weren’t simply given an image by an art director, editor or, worse, a marketing team. Odds are Salter was a conventional illustrator who probably thought the ending made infinitely more sense.

“Metamorphosis” was likely invented by Ovid, who posited the concept of shape-shifting by both humans and animals. Woolf refined it into four distinct phases–poetry, love, creolization (a fancy 16th century term for hybridization of different cultures), and gender change. It’s possible she was aware of the world renowned magician Harry Houdini and his illusion, Metamorphosis, as he was performing it the same time she was crafting Orlando. Onstage, the male magician, handcuffed and padlocked in a trunk, changes places with a female assistant, standing on top of the trunk, in the blink of an eye. In the 1960s, Broadway audiences saw the popular Doug Henning perform it in The Magic Show. Audiences throughout time have easily suspended disbelief for a confounding magic trick—they cheered Doug and his assistant, Dale Soules, for four successive years.

The movie. The importance of Preciado’s freely adapted documentary, which joins Tania Cypriano’s documentary, Born To Be (2019), as well as Sean Baker’s narrative drama Tangerine (2015), cannot be overstated. All three were and are critic’s choices, and the trio constitutes landmark cinema. One of Orlando’s 26 transitioning French trans persons may be speaking for all: “I’d like to write my own political biography one day, but Virginia Woolf’s done it for me.” Oscar Rosza Miller, pictured above, like 25 others transitioning, wears a ruff, a 16th-17th century costume accessory, which becomes the film’s brand image. Transitioning is explained in all its political, social, psychological, sexual, literary, and even surgical glory. It’s a daring cinematic concept—and thanks to Precadio’s inventive and innovative scripting ideas, it works for 103 fast-paced minutes like gangbusters.

The challenge, Preciado explains, is how to dramatize an Orlandoesque life as a gender poet in the midst of today’s binary and normative society. His solution is a series of arresting performance vignettes, with individuals reading, acting, singing and personally interpreting the novel vis-à-vis their own transitions.

Some are shot in pastoral outdoor settings, others on bare stages supported by a scrim and occasional snow or rain effects. One takes place in a Paris gun shop in which a cast member in Nordic costume comes in and trades a 1741 hatchet for a stuffed fox, in memory of Volumia Fox, a minor character in Orlando in which Woolf briefly plays herself. Another priceless scene plays out in a local hotel, in which the oldest cast member (Jenny Bel’Air) requests a room for herself and her pup (also wearing a ruff), and presents her doctored passport with Woolf’s name, bearing an issue date in the 1500s. (Jenny is politely but firmly asked to leave.) A third intricately staged scene shows a gowned and masked surgical team operating on a copy of the book itself, cutting away snippets of objectionable language (“Violence Is All”) often encountered in normative societies. It’s a doc packed with surprises. Christine Jorgensen, a GI who transitioned into a woman in Denmark, is the subject of a 1952 Movietone newsreel, shown widely in US theaters. And just when you’re becoming enraptured by some poetic passage, on comes a disco setting and a nonbinary chap belting out Preciado’s wickedly astute “Pharmacalbration,” in which you’ve never heard “poetic, prosthetic, magnetic” rhymed so artfully.

Virginia Woolf subtitled her Orlando “a biography,” but first and foremost it was a novel. A half dozen of the 26 participating cast are pictured reading it, probably for the first time, prior to a revealing sketch between a young man exploring the possibilities of gender change and a mindless psychiatrist who’s got the notion of a “female penis” stuck in his head. What Preciado, himself a trans male, makes crystal clear is that the greatest unknown within the transgender community is not how its members choose to alter their lives, but how the society they newly enter will receive those lives. What he envisions is a 2028 world in which a Supreme Court justice (acted here by Virginie Despentes) will declare “the abolition of sexual difference at birth, along with its legal and administrative registration,” thus granting “planetary, non-binary citizenship to all our Orlandos.” What this brave documentary demands is no less than the right to edit our own lives.

Anatomy Of A Fall; Justine Triet; France; 2023; 150 minutes

Did the handsome French teacher and dad, Samuel (Samuel Theis) fall to his death accidentally from an attic window? Or deliberately? Or was he pushed? The only other person at home in their French Alps chalet was his German wife and sometime writing partner, Sandra (Sandra Hüller). She claims to have been asleep. But she’s accused of murdering him.

After a century of courtroom dramas in the movies, nothing still holds audiences spellbound like a juicy murder trial. This one’s a superlative procedural written (by Arthur Harari and Triet) and directed by Triet with an acute understanding of how stressed and strained marriages can collapse into ruin. And how that kind of ruination can affect a bright, gifted 11-year-old son, Daniel (Milo Machado Graner) whose optic nerve was severely damaged in a childhood accident.

When a premise this stark is performed by a pitch-perfect ensemble cast, two and a half hours in the dark fly by. Totally opposing interpretations of the husband’s death are offered by equally savvy prosecution (Antoine Reinartz) and defense (Swann Arlaud) lawyer teams. Either Samuel’s head injuries were caused by being struck by a blunt instrument in the attic, or resulted when he fell head first onto a shed roof and tumbled down onto the ground. Theories rise and fall beside inconclusive evidence. Testimony is offered by reliable or perhaps untrustworthy witnesses. The emerging pattern is that Samuel—a teacher who home schooled his son while renovating their chalet and trying to kick-start his writing—was always running behind his more successful wife.

Sandra’s a published author with three novels of family life that freely borrow from her own parents’ and son’s journeys, but also integrate some of Samuel’s most promising ideas. She dislikes France. She’s bisexual and admits to sexual trysts with another woman. She blames her husband for his inattentiveness that caused Daniel’s eye injury. Samuel drinks heavily, blasts rap music and begins abusing pills—Sandra recalls spotting aspirin in his vomit, another incident that will have additional meaning later in the movie. Both partners are not in good shape—but it’s Samuel, not Sandra, who’s wearing out fastest.

Late discovery surprises abound—an audio recording of a last furious kitchen confrontation between the couple is played for the jury, but Triet shows in flashback how most of it plays out in a harrowing centerpiece scene of fury and rage. Triet is adding us to the jury box. Screws are tightened on the accused. The triumph of Anatomy of a Fall —what makes it the must-see drama of the fall season—is not just its stellar script and dedicated cast, headed by a luminous Hüller. The real verdict, the one you’ll carry out of the theater and remember, is rendered partly by a jury, but more significantly by the son along with his loyal lifelong companion, his dog. His dog? How’s that work? Well, Anatomy of a Fall won the Cannes festival grand prize, the Palme d’Or, in May. And it shared that award with Messi, a Border Collie cast as Snoop, who won an added critics’ award, the Palm Dog. Ms. Triet regards that animal as a full-fledged cast member, and without question, you will too.

Close Your Eyes; Víctor Erice; Spain; 2023; 169 minutes

NYFF has a long tradition of honoring the work of legendary directors, as well as welcoming their newest efforts. Erice’s seminal drama, the picture he’s most remembered for, The Spirit of the Beehive (1973), came out nearly 50 years ago, near the end of the repressive Franco regime in Spain. Erice’s concept was a rural village of children who watch the original 1931 Frankenstein. They view the edited version where you see the monster picking daisies with a little girl in a meadow, but you don’t see him picking up the child and hurling her into a lake, drowning her. The kids in Beehive spend their days wandering the forests, looking for Franco soldiers to befriend, and wonder why so many people want to capture and hurt the Frankenstein monster. In 1973 Erice was also directing tv commercials, and the picture remains a one-off classic, a novel and metaphoric child’s eye view of the rise of fascism.

If you’re wondering what’s happened to Erice, part of the answer can be found in Close Your Eyes. It’s the fest’s most endearing wild card, in which two completely different stories find men searching for a lost loved one. Plus it’s a film rooted deep In the love and loss of traditional motion pictures, the kind of pre-streaming, pre-Internet gem that NYFF used to put up as its opening night. Bookmark it for cinephiles who’ll subway, bus or walk miles to watch movies still projected in 35mm.

The story opens outside Paris in 1947 at the estate of the wealthy and ill M. Levy (Josep Maria Pou). He engages a trusted associate, Garrel (Jose Coronado) who helped endangered Jews cross the Pyrennes during the war, to find his missing half-Chinese daughter. He has one picture of her at 14. Levy wants to gaze into her face one time before he dies. He believes she’s somewhere in Shanghai, and directs Garrel there.

At which point Close Your Eyes restarts itself, with a whole new premise and cast of characters. We’re in Madrid, where a former film director named Garay (Manolo Solo), now languishing in a beach shack and eking out a living translating film books, is being interviewed on a local program about his short-lived career. He’d made one picture and started a second, an adventure drama which shut down when its temperamental star, Julio Arenas, suddenly walked away and vanished. This effectively ended Garay’s career as well as that of Arenas. On impulse, the director visits Max (Mario Pardo), his former editor, who’s also wasting away but maintains a warehouse of film memorabilia. All the elements of the partially completed film, titled The Farewell Gaze, are preserved. Garay plays an audio tape of Julio’s line rehearsals—and what we hear is the exact scene at the estate that started the movie. Ah! Julio is playing the friend tasked by Levy to find his daughter.

How will the director of Close Your Eyes ever resolve this peculiar dilemma? It takes a while, and if you’re a movie buff you’ll settle in instantly. Along the way you’ll meet Garay’s old girlfriend and Julio’s grown daughter, Ana (Ana Torrent, still recognizable from her child role in The Spirit of the Beehive). And you’ll hear a lot of ruminations and fond recalls of what moviemaking was once all about. There’s a gem of a scene one night at the shack when Garay picks up a guitar and joins a young man in singing an old cowboy ditty, “My Rifle, My Pony And Me,” which Dean Martin and Ricky Nelson rhapsodized on in Howard Hawks’ 1962 oater, Rio Bravo. Close Your Eyes is that kind of movie.

Eventually the missing actor is found by Garay in a local nursing home, healthy but afflicted with dementia. (He’s also wonderfully played by Jose Coronado.) Julio and his former director, who were once Navy pals together, are reunited. A screening of those scenes from The Farewell Gaze, which we’ve heard him rehearsing, is arranged on a local cinema screen. And there Erice works his magic one more time, showing you what would have happened if Julio had not walked away and Garay had finished the picture he’d written. If you truly love movies, you will not watch Víctor Erice’s triumph with dry eyes.

All Dirt Roads Taste of Salt; Raven Jackson; United States; 2023; 97 minutes

There was a time in the long, long history of the New York Film Festival when a full-length feature film constructed like this—modest in scripted word count, yet transforming in captured image count—might have turned up in a category originally called Views From The Avant-Garde. It could have happened decades ago, for this particular story and rural setting stand outside time. (A few soundtrack tunes suggest the late 60s). Like many films shown in Views, a primary theme is outdoor summer weather, especially water and rain. The director lensed her story near Jackson, Mississippi, in Kodak 35mm film. Very Old School. (Now very avant-garde.) Ms. Jackson credits “the many generations of my family who entered the soul of this film with me.” As a festival category, Views has morphed through the years into Projections, then Currents. There are eight pages of Shorts (including Currents Shorts) in this year’s program.

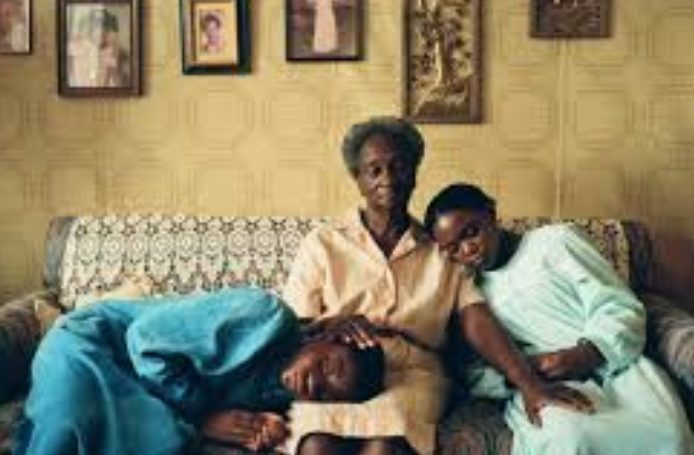

Raven Jackson, who built her chops making shorts, has made an unprecedented leap with her 97 minute cine-memoir. She’s created a master class in portraiture, focusing on a Black Mississippi girl growing into womanhood before your eyes. There’s not a hint of urban or white encroachment. Jackson’s Black Gaze is steady and always, always tender. This is a family-friendly movie in a festival rarely intended for family viewing. Maybe that’s why Jackson’s first feature landed smack in the heart of the fest’s coveted Main Slate. The picture’s importance is on a par with Julie Dash’s 1991 Daughters of the Dust, the first feature by a Black female director to receive widespread distribution. Jackson has seized a unique opportunity to craft a particular kind of Black historical drama never made before. It probably didn’t hurt that one of her four producers is Oscar winner Barry Jenkins, who knows a thing or two about fashioning beautiful narratives, and produced one of Jackson’s shorts back in her salad days. Salt now approaches a robust distribution rollout, with the super-savvy A24 ready to launch it to the world. Watch it soar.

In Jackson’s world, everyone speaks softly and respectfully. The loudest sounds are an occasional thunderclap and a baby’s fussing. The temptation to describe the excellence surrounding MacKenzie (“Mack’s”) life by simply citing a list of camera setups, is irresistible: There are closeups of hands clasped, hands stirring mud and silt, hands digging out salt from dirt walls, hands warmly bathing a newborn, hands caressing hair, hands measuring a pregnant belly, hands lifting clothing to pee in a field, hands forming a bucket brigade to try and extinguish a house on fire.

All in all, through nearly two dozen interconnected vignettes, Jomo Fray’s camera is busy trailing the movement or solitude of hands belonging to Mack and her family. The hand holders include Mack (Charleen McClure), older Mack (Zainab Jah) young Mack (Kaylee Nicole Johnson), and toddler Mack (Mylee Shannon), plus Mack’s mother Evelyn (Sheila Atum), father Isaiah (Chris Chalk) sister Josie (Moses Ingram), young Josie (Jayah Henry), young boyfriend Wood (Preston McDowell), mature boyfriend Wood (Reginald Helms, Jr), two kissing teens (Taylor Vigee and Landon Arnold), and Grandma Betty (Jannie Hampton). This is a substantial acting company, and part of the director’s singular vision is permitting the viewer to experience only glimpses and slivers of their immense talent. Jackson’s created a family and a community we long to get closer to.

The Thai editor making sure you fully absorb all this handiwork and hugging (but not a second longer) is Lee Chatametikool, a frequent collaborator with slow cinema’s reigning master, Apichatpong Weerasethakul. Much of the time Salt’s unified cast is subsumed into its settings of nature, never more so than a few minutes spent on two youngsters nestled in the spreading branches of what must be the most gigantic tree still standing on Southern soil. The tree imagery instantly brings to mind Gordon Parks’ The Learning Tree in 1969, and some of Parks’ indelible imagery. Jackson is standing on Parks’ formidable shoulders, but she’s absolutely standing on her own.

About Dry Grasses; Nuri Bilge Ceylan; Turkey; 2023; 197 minutes

Bet you never expected MeToo, Title IX and challenges to academic freedom to turn up in the wintry wilds of Turkey’s East Anatolia. When a world-weary Samet (Deniz Celiloglu) steps off a school bus into knee-high snow drifts, and trudges through near-whiteout conditions toward a ramshackle bunch of one-story buildings (army base, liquor dealer, school) in the middle of nowhere, we have no idea what awaits this middle-age, middle school art teacher. He’s a competent photographer who shoots the locals in their vast landscape. We sense his colleagues are beaten down by the weather, the government and the poor local economy—items like perfume and tracksuits left in airports are their finds of the day. Are we in for 197 minutes of this?

Stick around. Samet must be a well-liked teacher because a cute seventh grader, Sevin (Ece Bagci), leans all over him. She’s tagging along with him down the hall, their arms casually around each other’s backs. Samet gifts her with a pocket mirror and hurries her off to class. Later that day, the administration conducts a search in his classroom of student’s belongings that don’t belong in school—a cigarette lighter, pen knife, a personal diary belonging to Sevin including a letter that falls out. A higher-up reads it and hands It without a word to Samet—it’s a love note to him from Sevin. He reads it in his office just before Sevin bursts in, demanding it back. He says he didn’t even open it and tore it into shreds. We know this is a lie and the girl doesn’t believe him—she’s really upset, almost in tears. Any student or faculty member in the world watching this will be riveted, because we know what’s coming.

Samet and his housemate Kenan (Musab Ekici), who once herded sheep for his dad and now teaches at another wilderness school, are both hauled Into a meeting with the principal (Onur Berk Arsnanoglu, a perfect bean counter) and a district superintendent representing the governor’s office. Charges of “inappropriate conduct with two students” are laid out. We learn the complaints were made by Sevin and another girl, and involve Kenan pinching a girl’s cheek and Samet putting his arm around Sevin in the hallway. The governor fears firing both teachers will cause a worse scandal than simply disciplining them, so they’re let off with a severe warning. Samet is livid. He’s been onboard four years in a location he hates, with an administration he now fears, teaching girls who he’s seen can manipulate their feelings about teachers into complaints that may destroy them. He orders Sevin out of his classroom and berates all “schemers.” It’s another perfect storm in academe.

Director Ceylan then wisely introduces the kind of counterpoint we’ve hoped for—an English teacher, Nuray (Merve Dizdar), from the area high school, who’s moved back to her parents’ home after losing half a leg to a suicide bomber. She modestly admits to painting at the “community education level,” and hopes one day to restart her life in Istanbul. Maybe this is the romantic interest Semet has longed for. With her folks away, Nuray invites Samet for dinner. In a half-hour dialogue over a bottle of wine that’s the movie’s centerpiece (and that won the quietly buoyant Ms. Dizdar Best Actress at Cannes), the two share their very different takes on the world. He admits to being selfish and wearing “the weariness of hope.” She’s an optimist and activist, a dedicated teacher who’ll go the extra mile for her students and society, and she understands the bleak restrictions they live with as teachers, but won’t be defeated by them. Nuray has the energy and transcendence Samet hoped for in his 7th grader. The adult teacher weighs Samet’s inferiority as “the useless, rundown mill” he’ll admit to being, but invites him to stay over, anyway.

About Dry Grasses is an absorbing, socio-political essay that, much like Romanian cinema of the past two decades, shares a deeply cynical perspective on how governments fail their people. Dizdar and Celiloglu match each other handsomely in a debate that bristles with working class disappointment, resentment, even despair. As winter finally turns to spring and grasses replace snow at last, graduation day arrives. Sevin, having long forgotten her crush as well as her crushing complaint against a teacher she once adored, shares an epilogue with Samet. You may or may not agree with it, but you’ll find it extraordinarily touching.

Kidnapped; Marco Bellocchio; Italy; 2023; 134 minutes

Film at Lincoln Center, to its immense credit, hasn’t fallen under the sway of Audience Awards, like so many fests locally and nationwide. Getting curated into NYFF has always been acknowledged as its own reward. Thus first time feature directors like Paul Preciardo and Raven Jackson remain on equal footing with esteemed masters like Víctor Erice and the helmer of our final Critic’s Choice, Marco Bellochio. This 82-year-old director’s most recent picks in The Independent were The Traitor (2019), about a dedicated foot soldier who killed his way to the top of the Sicilian Palermo mafia during its struggles for control of the international heroin trade in the 1980s and 90s, and Exterior Night (2022), a five-hour dissertation on the kidnapping and assassination of Aldo Moro, Italy’s former prime minister in 1978, by the terrorist Red Brigade.

As in his earlier Vincere, the director’s 2009 re-creation of the hapless and frenzied woman who fell in love with Benito Mussolini, who was Hitler’s demonic second-in-command, Bellocchio’s strongest assets are casting and production design. His films are uncannily alive with actors who seem to have inhabited the roles they play, all their lives. And his pictures are lavishly mounted with extravagant care and baroque splendor that matches their fast-paced emotional urgency. Like Martin Scorsese and Ridley Scott, Bellocchio is a precisionist—you know where you are every minute, especially when your heart is in your throat.

His new film is set in Bologna in 1852. The city’s Jewish population leads an uneasy existence under Pope Paul IX, the church’s last ‘pope king.’ While Paul has released some families like the Morturas from the ghettos they were forced into, he’s a church/state nationalist who rules with a doctrine of papal infallibility. Freedom of speech has vanished, and Paul is an anti-Semite policeman. The Mortura family watches in anguish as its 6th child, Edgardo, is seized at age six, by order of the Tribunal of the Holy Office, having been baptized by a servant girl. The father, Momolo (Fausto Russi Alesi, grieving and shaken) is told to “pack a change of clothes for your son,” for by church decree he will remain a Christian for eternity. Even to get him back, the Morturas must convert to Christianity.

Kidnapped follows Edgardo’s life from age six through young manhood. The burning issues are how he survives as a ward of the Catholic church, whether he will ever return to his family, and whether he will reclaim his life as a Jew. Paul’s reign ended with the Italian army’s invasion of Rome in 1878, which the movie vividly plays out. You can see why Bellaccio was drawn to it. (Steven Spielberg had the rights for a while, but passed in favor ofThe Fabelmans, in which he’d take on the less demanding task of re-creating his own childhood.)

The captured boy Edgardo (marvelously played by a totally believable Enea Sala), is transported to Rome and assigned to the keeping of Monsignor Felliti (Fabrizio Gifuni, icily effective). Shy and naturally obedient to authority, Edgardo is quickly absorbed into the everyday instruction and rituals of his captors, though when he’s visited by his shattered mother (a fiercely devoted Barbara Ronchi), we see he’s struggling to cling to his Jewish identity and beliefs. Jewish radicals try to steal the boy back but grab the wrong child. The boy, later seen as a young man (convincingly acted by Leonardo Maltese) won’t be broken easily.

Bellocchio’s in assured control of his narrative, and he’s not shy about inserting fantasy moments. Outraged newspaper cartoons of the boy’s snatching suddenly animate off the printed page. In the pope’s nightmare dream, he’s circumcised by rabbis surrounding his bed. And in one mesmerizing sequence set in an empty church sanctuary at night, Edgardo approaches a giant figure of Jesus on the cross, removes the nails from his hands and feet, and watches without emotion as a live action Jesus climbs down from the cross and exits the church. Bellocchio fearlessly builds these satiric touches into a mosaic of terrified imprisonment that would sink lesser directors and movies.

The scenes between Edgardo and Pius IX (played with a devastating mix of affectionate charm and autocratic vengeance by Paolo Pierobon), are the picture’s most riveting moments. The pontiff regards the boy as a pawn, a symbol of his church’s ultimate victory over Judaism. In a playful game of hide-and-seek on the church lawn, Pius conceals the boy in his robes. Yet in a later scene after the youth has been baptized and consecrated into Christian life, Edgardo suddenly attacks his guardian in a crowded church service. It’s a shocking moment, but the Pope cunningly forgives him, demanding Edgardo’s ultimate supplication by licking the floor and making the cross three times with his tongue. And Edgardo obeys.

Kidnapped, like Petzold’s Afire, may suddenly find itself as exactly the right movie at the right moment. We watch Pius IX’s reign begin to crumble and topple in the 1860s and 70s—both Father Feletti and the servant girl are arrested, while epilepsy and a stroke take down the pope. A mob of citizens, emboldened by being set free by the Italian army’s overthrow of the church, calls for the pope’s coffin to be tossed into the Tiber river. Certain parallels with tragedies in embattled lands today—including innocent seized hostages—are inescapable and heartrending. If our past is truly prelude to our present, great world cinema can reflect that, both in our memories and in the lives we live today. NYFF curated these six memorable and timeless movies into its 61st edition, and Kidnapped is another prime keeper.

This concludes Critic’s Choices. Watch for Brokaw’s picks in DOC NYC, America’s largest documentary festival, Nov. 8-26.

Regions: New York City